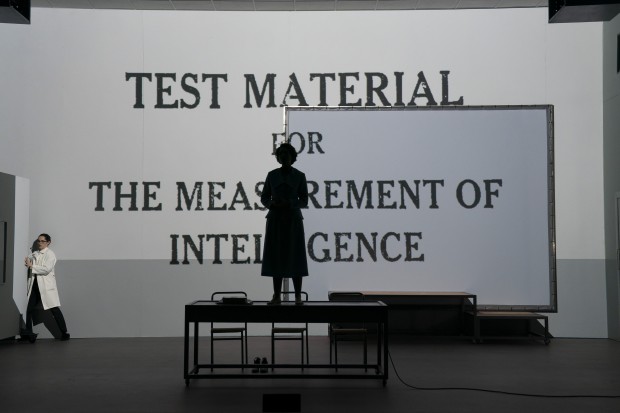

A scene from Aida

Layering Irony and Politics

Irish National Opera’s ambitious first year is drawing to a close. The new company, risen from the ashes of Wide Open Opera and the Opera Theatre Company, chose an operatic staple to end the season, Verdi’s Aida, with Orla Boylan singing the title role, alongside Imelda Drumm and Welsh tenor Gwyn Hughes Jones in the lead roles.

Aida is often told as a love triangle between Aida, the enslaved Ethiopian princess, Radamès, captain of the Egyptian guard, and Amneris, the princess of Egypt, set against the backdrop of the Ancient Egyptian conquest of Ethiopia. The opera normally resists adaptation from its setting, but director Michael Barker-Caven, along with set and costume designer Joe Vaněk, brings the story’s imperialism to the centre with a modern/futurist look, opening with a translucent glass cube in which shadowy figures grasp and grope at the walls.

The production places enormous emphasis on the oppressive actions of the Egyptian regime, who are dressed in modern military and political regalia, and on the split loyalties of the central lovers to each other and to their countries. In the first two acts, background events are as important as those in the foreground: as Gwyn Hughes Jones’ Radamès declares his love for Aida, young women in headscarves flee armed soldiers at the back of the stage.

All-Seeing Eye

The opera is visually overwhelming. Aida, particularly its second act, is a spectacle in any case, but this production layered irony and politics onto every image. The decrepit king is brought out in a wheelchair to the sounds of a triumphal march. Aida’s face, in photo projection, hangs over the stage in the first scene; later, where her eye had been, there is now the symbol of the All-Seeing Eye enclosed in a triangle, not unlike the one on the dollar bill. There are cheerleaders and terrorists and protestors and recreations of scenes from Guantanamo Bay. There are male strippers in military fatigues doing the Macarena.

If it seems like this ostensible review of the music has been hijacked by a review of the visual production, then you know how I felt watching it. Aida is a balancing act between visual spectacle and song, and, particularly in the first two acts, the scale was so tipped in one direction that it was hard to focus on the music. To an extent, that was the point. The relentlessness of imagery reflected, as much as anything, the 24-hour news (or social media) cycle, and the ease with which it’s turned to propaganda.

Bright as a spotlight

Orla Boylan and Imelda Drumm, both newcomers to their roles as Aida and Amneris, did themselves credit. Boylan’s voice was bright as a spotlight, sounding out clearly above even the full choir and orchestra. In her most intimate aria, ‘O Patria Mia’ in Act III, as she mourns her homeland, her performance was at its most vulnerable. At one point, Boylan turned her back to the audience, and almost subvocalised the words ‘mai più’ (‘Never more’), the tiniest and most heartbreaking sound.

Amneris has the most powerful visual moment in the opera, pleading Radamès’ innocence as his trial for treason is conducted offstage. Drumm radiated guilt and despair, lying alone on a dark stage, leaping up occasionally in passion. The set design was at its most effective here too, almost minimalist, surrounded by black walls as she wilted under a white spotlight.

As Radamès, Gwyn Hughes Jones was the most experienced performer in his role, and his voice was fine and sweet, tinged with real pain in his songs in Acts III and IV. Out of all the performers, though, Hughes Jones was the most inclined to stand at the front of the stage and sing out to the audience, to declare his love alongside, rather than to, Aida.

Gwyn Hughes Jones and Orla Boylan

Walls of sound

Overall, the musicianship was of a very high standard. The large choir and the RTÉ Concert Orchestra, under Fergus Shiel, were quite capable of creating the necessary walls of sound, and other stand-outs among the cast included the bass Manfred Hemm delivering the Priest’s lines with staid directness, and character actor Graeme Danby playing his part, as he did with The Marriage of Figaro earlier this year, as much with his body as with his voice.

But the visual production itself is the star of the show. Credit is due to Barker-Caven and Vaněk, not least for successfully relocating an opera so steeped in Egyptian-ness, and for highlighting the universality of its themes. The extent to which the production works on an individual basis is a question of whether, and how quickly, the listener is prepared to accept the centrality of the visuals. Because this is not a traditional Aida.

But, from Irish National Opera, who would have expected one?

The final two performances of Aida take place this evening, Thursday 29 November, and on Saturday 1 December at the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre. Visit www.irishnationalopera.ie.

Published on 28 November 2018

Brendan Finan is a teacher and writer. Visit www.brendanfinan.net.