Naomi Louisa O'Connell and Stephanie Dufresne (left) in 'Least Like the Other'. (Photo: Pat Redmond)

An Opera of Sympathy and Fury

About halfway through Least Like the Other, the music finally breaks. Brian Irvine and Netia Jones’ 2019 INO opera describes the life of Rosemary Kennedy, sister to the former US president, who was diagnosed with an intellectual disability, beginning at her tortuous birth – the nurse pushed her head back into the birth canal to wait for the doctor since, if he wasn’t there for the birth, the text of the opera implies, he wouldn’t be able to collect his $150 fee – through rearing by her tyrannical mother and distant father. Kennedy was eventually lobotomised in 1941, aged 23, and institutionalised until her death in 2005.

The break in the music comes, and what has been frenetic and intense for so much of the preceding 35 or so minutes is left behind. The stage, until now lit in sterile white or paper sepia, is bathed in blue. The walls of the stage become the water of a swimming pool, paradoxically allowing the audience – and Rosemary – a moment to breathe. We’ve been told that as a girl she loved to swim. The music here is an excellent invocation of water, written for solo piano, chords undulating gently. But the harmony is also brittle, a reminder that this respite is temporary. We’ve read the synopsis. We know where this is going to end.

Irvine and Jones’ work premiered at the 2019 Galway International Arts Festival and has returned with a tour of Dublin, Cork and Limerick. This is the first outing of the work in its current form, with a recorded orchestra distributed across 16 speakers, conducted (as are the performers on stage) by a pre-recorded video of Fergus Sheil. The lofty words in the programme note, that this would ‘give the audience an experience of the music as if inside the very belly of the beast’, did little to instil confidence, feeling rather like marketing hype. But the execution, where it counts, was excellent, and from the first moments you forget that what you’re hearing is not live. The musicians also punch above their weight, the fifteen performers hitting with the force of a full orchestra.

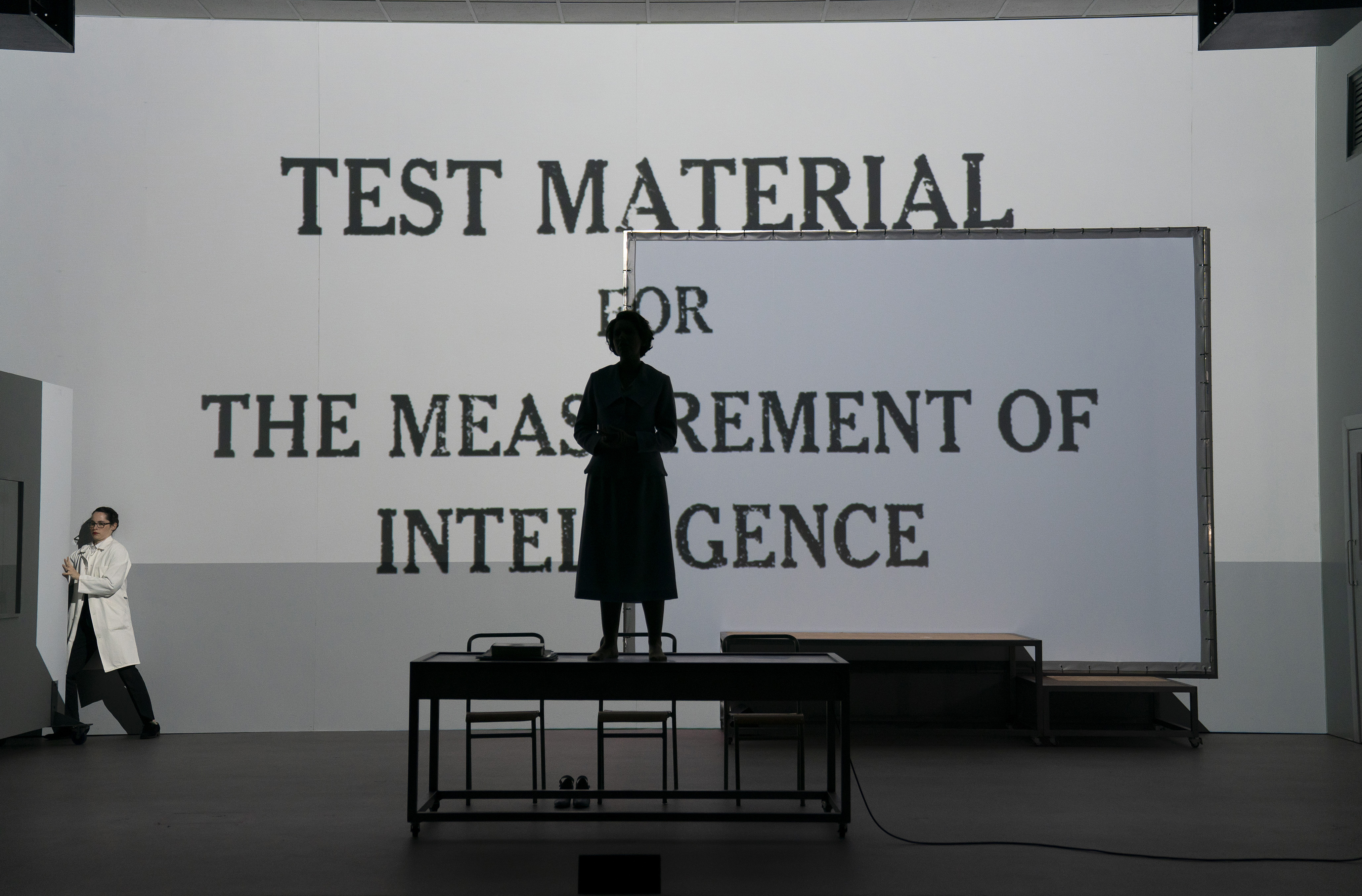

Outside of the swimming pool sequence, training is a key theme of the opera. Rosemary is always at the whim of external forces – usually her parents – in training to be a socialite, to be more intelligent, more moral, thinner. The whole work has the fragmentary structure of a nightmare, a hell of constant discipline. In the first half, we see two intense quizzes. In the first, questions of general knowledge are thrown out by Kennedy’s mother, Rose. The questions are relentless, on wildly varied and jumbled topics – geography, history, literature, mathematics – and the answers don’t matter. They’re ignored as the next question is delivered. In the second, the answers are deadly important. The questions, now a variety of multiple-choice puzzles, are just as relentless. We watch as Rosemary, drowning in the constant flow of interrogation, struggles to respond, sometimes picking up a megaphone just to be heard.

Irvine’s career is marked by his frequent collaboration with artists in other fields. Director and designer Jones brings a work that is theatrical through-and-through, allowing a simple stage to become a dining room, a classroom, a medical examination room, a ballroom. The choice of scenes allows an examination of Kennedy’s life and a critique of attitudes towards women, both in the past and now. (The diet to which she was subjected, for instance, seemed honestly more healthy than some modern trends.)

So fully is the work a theatrical one that I rarely found myself fully conscious of the music, in spite of its frenetic energy and volume. Even quieter moments, with the exception of the swimming pool, are often juxtaposed against music with an unsettling, jerky energy. The mezzo-soprano Naomi Louisa O’Connell was at the heart of it always, deftly managing the sometimes breakneck changes of style and portraying Kennedy’s inner turmoil and outer placidity. On stage with her were the actors Stephanie Dufresne and Ronan Leahy, both portraying a variety of influences surrounding Kennedy – doctors, teachers, family; sometimes even Kennedy herself, other times reading descriptions of medical procedures she underwent, while offstage Aoife Spillane-Hinks read her dialogue often with an eerie calm.

All this contributes to the broiling chaos of a powerful work, one in which recorded music and onstage action are thoroughly integrated; where the sociopolitical themes and the individual life at the centre are examined simultaneously, like opposite ends of the same telescope. It is a critique of the world in which Kennedy lived, in which we still live, but is never voyeuristic. It is a work of sympathy and fury.

At the end of the performance, Rosemary Kennedy walks on stage slowly, almost as in a dream – though the music is a manic chaos. She makes her way to a drawer, reaches in, takes out a photograph and almost ritualistically tears it in half before flying into a rage, destroying everything she can as the stage lights flash and go out. The end, it seems, as she leaves the stage in darkness, but then the walls are again bathed in the light of water, now with an artificial greenish-purplish tinge, like someone spilled oil on the film. The music of the earlier swimming pool scene, or something very like it, returns, now played on strings to the empty stage as perhaps we drift just under the water, looking up at the sky. Maybe swimming. Maybe drowning.

Least Like the Other continues at the O’Reilly Theatre in Dublin from 16 to 18 September, then Cork Opera House on 22nd and Lime Tree Theatre, Limerick, on 25th. Visit www.irishnationalopera.ie.

Published on 16 September 2021

Brendan Finan is a teacher and writer. Visit www.brendanfinan.net.