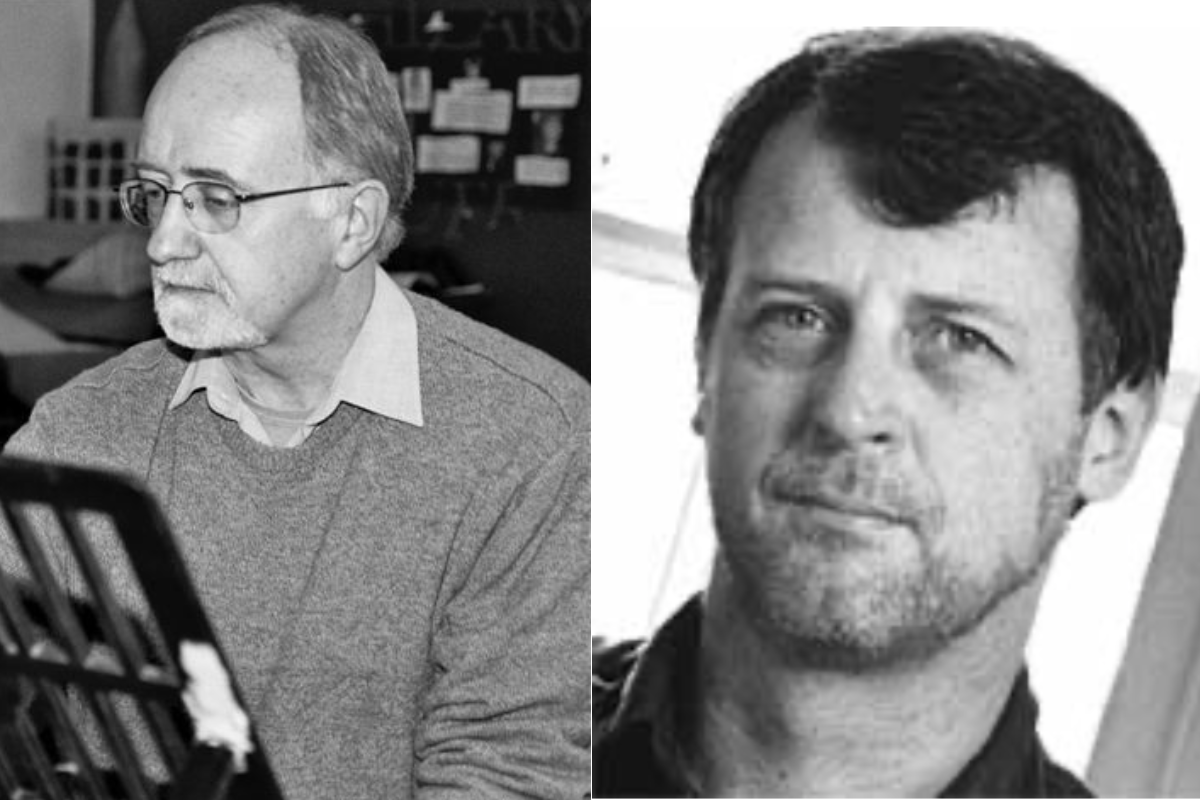

Raymond Deane and Ronan Guilfoyle

E-debate: Music and Society – Raymond Deane and Ronan Guilfoyle

Dear Ronan,

In ‘Contemporary Music?’ in the Nov-Dec JMI, you raise a number of important questions about the relative popularity of jazz and contemporary classical music.

You describe an enthusiastically received performance by Steve Coleman at the Mermaid in Bray, ‘music that was challenging, chromatic, rhythmically complex’, but accessible to the full house (242 seats) because of its ‘clearly perceptible pulse’ to which the audience relate because ‘they live in a society whose musical soundtrack is almost all based on… a pulse…’. Seven times in the course of the article the word ‘challenging’ is used to describe the jazz you admire which no matter ‘how atonal [it may become], how chromatic, how complex’ retains its popularity because of this groove stemming from ‘The cultural empire of America’.

This might be taken to mean that the apparent ‘challenge’ of this music is dissipated by the presence of a pulse which, however complex, is ultimately constant. The ‘challenge’ of much contemporary classical music, however, is that the sonic tight-rope onto which it invites its listeners is without any safety net either of pitch (fixed tonality) or rhythm (constant pulse).

You ask: ‘If you are a contemporary composer…, how can you ignore the music that surrounds you?’ (‘…albeit often very annoyingly’, you concede). You are puzzled that much of the ‘contemporary music’ that you hear bears ‘no relation to the music of the society within which [its composers] live.’

The unwritten implication is that a composer must accept without question the norms – the ‘understood rhythmic template’ – of the society within which he/she lives. The failure to conform to such norms means that the composer ‘ignore(s) the music that surrounds’ him or her, which surely doesn’t necessarily follow. Therefore in a society in which US cultural imperialism has imposed a constant pulse, our music must also manifest such a pulse if it is to be accepted by and sold to listeners whose ears are thoroughly indoctrinated by this music in all its forms, just as their minds are indoctrinated by US societal norms.

This is a precise inversion of Adorno’s position on jazz, which he hated because it embodied, to his Viennese ears, the commodification of Americanised modernity. Adorno, as we know, celebrated Schoenberg because his music shunned the marketplace, thus constituting an implicit critique of society.

Adorno, therefore, expects worthwhile music to embody a critique of society, whereas you believe that it must conform to societal norms. But surely only a dialectical approach can do justice to the full experience of music, one that evaluates both its relationship to the society from which it emerges and its effect on the listener, as well as the tension between these.

Furthermore, does the fact that we live within a society impregnated with American cultural imperialism mean that we must embrace it and embody it in our music? Cultural imperialism goes hand in hand with imperialism pure and simple, of which we are seeing a horrendous resurgence in our time, whatever ‘left-leaning’ composer Donnacha Dennehy may think (he refers to the ‘death of imperialism’ in the same JMI issue, and should surely lean a little further so that he can notice Palestine, Iraq, Shannon Airport…).

Of course, for contemporary classical composers to assert their independence of the norms of society while still seeking subsidisation from it involves them in a set of egregious political and ethical paradoxes. These are issues that deserve to be teased out, yet they have confronted artists throughout history and are unique neither to our time nor our society. Your argument boils down to the assertion that composers should passively conform to the norms of the society in which they live or else keep silent, an essentially authoritarian and anti-utopian viewpoint, and one that would have deprived the world of much great music had it been adhered to in previous centuries.

All the best,

Raymond

Dear Raymond,

Regarding your interpretation of my argument being that ‘composers should passively conform to the norms – ‘understood rhythmic template’) – of the society in which they live or else keep silent’, this is not what I intended to convey and I don’t think I ever said that. Obviously a decision on the part of a composer to deliberately remain aloof to the music of the society that surrounds him or her is an understandable stance should the composer in question feel that this is important. However, what I am saying is that if one ignores the music of contemporary society, then one shouldn’t be surprised if one’s music is itself ignored by that society. Many composers bemoan what they see as shabby treatment by society and audiences, yet at the same time refuse to engage with the music of that society. These composers want it both ways.

As to my second point regarding the purpose and acquisition of musical language, I believe that this stance of remaining aloof, though understandable as an intellectual choice and political statement, is questionable on a musical level. Music is a language and is perceived and acquired aurally in the same way that spoken language is. I have a Dublin accent because I was born in Dublin and absorbed the rhythms and inflections of speech of the people around me – the society in which I was born and raised. Any later decision on my part to reject that accent and vocabulary would entail a deliberate, and, in my opinion, artificial effort to obliterate the sounds and rhythms of the language surrounding me. My expressing myself as a Dubliner does not automatically make me a passive conformist – that can only be determined by the content of what I say. In music similarly, my use of the jazz idiom – something that I grew up hearing in my childhood – to express myself does not automatically make me a victim of American cultural imperialism, nor a passive acceptor of the norm. Do you really believe that deliberately shutting your ears to what’s around you automatically makes you a more valid musical commentator on society? I don’t accept that at all.

In most societies music is part and parcel of everyday life, its character reflecting the society from which it comes. Music is learned aurally and absorbed through musical osmosis rather than being taught in a formal classroom situation – it is learned and acquired in the same way as language. Jazz is no different – it has always reflected its surroundings. Its origins are rooted in the reaction of Afro-Americans to the music of their own society and the alien one in which they found themselves. Thus the music grew in an organic way – real contemporary music that was both innovative and reflective of the society from which it came. That continues to this day. Jazz has outgrown its Afro-American roots and become an international musical language. It is at once innovative and rooted in contemporary society. Yet its inherent improvisatory creativity ensures that it never becomes mainstream or passive, but allows and ensures constant change. This is its great strength. European art music also achieved this balancing act in times past – the music of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy and Bartók, to use just a few examples, was innovative yet reflective of and rooted in the society from which it came. Rather than standing apart from the music of contemporary society these composers engaged with it and their music grew organically from the society in which they lived.

As to Adorno and his hatred of jazz – first of all when he wrote his ‘A Farewell to Jazz’ and ‘On Jazz’ he was familiar only with ersatz German versions of jazz or commercial big bands, all of whom were very far removed from the creative centre of jazz. Adorno’s writings on jazz are highly discredited now and even a cursory read of his opinions makes it obvious that his knowledge of the history, ethos, techniques, concerns and philosophy of jazz could be written on the back of a stamp. But he wasn’t alone in his hatred of jazz – jazz was banned as ‘decadent’ by the Nazis, by Stalin’s Soviet Union, and had a campaign directed against it in Ireland in the 1920s by the Catholic Church. Any music that can offend Hitler, Stalin, the Catholic Church and Theodor Adorno must be doing something right!

Sincerely,

Ronan

Dear Ronan,

I don’t know who these composers are who ‘bemoan what they see as shabby treatment by society and audiences’. Many people who care about contemporary classical music believe that if the state values the arts for their own sake, as it claims, then it should not discriminate against specific art-forms. They believe that all forms of ‘minority’ music are discriminated against within a state that panders to the illusion that Ireland is a ‘literary’ country. Similarly there are those who believe that ‘difficult’ music is only difficult because people hear too little of it, and because musical education, where it exists at all, is too narrowly focused. To use your analogy with language, there is little doubt that Irish would be flourishing today had our educational system not made such a mess of teaching it.

Alas, you make an identification with music rather than an analogy – ‘Music is a language and is perceived and acquired aurally in the same way that spoken language is.’ This is untrue: music is not a language. It lacks a codified grammar, syntax, and vocabulary that must be universally agreed upon (give or take a few often fatal ambiguities!) if people are to communicate, however badly. Terms like the ‘grammar’, ‘vocabulary’, or ‘accent’ of music are metaphors, useful in some contexts, dangerous when taken literally. Your ‘use of the jazz idiom… to express [your]self’ is not the same as using Dublin-accented English to express yourself, because the word ‘express’ means something different in each case. Music of itself doesn’t ‘express’ an unequivocal message that is ‘understood’ by people sharing its ‘vocabulary’ – these are the conditions of everyday language-use. To understand people speaking another language I must learn its grammar, syntax, vocabulary, and perhaps script. To ‘learn the language’ of music of whatever kind, the act of repeated listening suffices to a considerable degree, precisely because there is no unequivocal ‘content’. No amount of listening to Swahili on the radio will bring about an elementary level of comprehension of what is being said.

Your analogy between Afro-American music and European art music falls flat when one examines the composers you mention. For space reasons, let’s just take Bartók. He used materials from Hungarian and other peasant societies, whereas he himself lived in Budapest, a society within which the ‘template’ was ersatz gypsy music and Viennese dance music. The materials he chose for his revolutionary music were therefore deeply alien to the society within which he lived. You would equate the process whereby the primary material ‘grew organically’ from peasant society with the process whereby Bartók transformed it into something rich and strange. It is no insult to the wondrous folk music of Hungary to say that these are two totally different processes.

Furthermore, is there not a profound difference between a template that ‘grows organically’ and one that is imposed by US imperialism? If I oppose the latter daily in my political activism I’m not going to embrace it in my music.

You’ve misunderstood my reference to Adorno. Of course he had no comprehension or knowledge of jazz, and his high-culture bias led him to defame it. I believe that your bias in favour of jazz leads you to make untenable assertions about other forms of music, and indeed about jazz itself: you consistently overlook that major strand of free jazz that excludes pulse and groove, and equate ‘all jazz’ with jazz based on a constant pulse.

All the best,

Raymond

Dear Raymond,

You take me to task for equating music and language. I hadn’t intended to make such an exact comparison, but to make the point that music is acquired in the same way as language is. Perhaps I could have phrased it better like this: music is similar to language in that it is acquired aurally in the same way that spoken language is. Now this is true. Music is generally agreed to have its origins in the intonations of excited speech, nonverbal voice signals, or significant inflections of the voice in tonal languages. Some auditory analysis skills used in the processing of language – such as blending and segmenting sounds – are similar to the skills necessary for music perception – skills such as rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic discrimination.

It has also been shown that infants, in any culture, respond automatically to rhythm, whereas knowledge of scales and harmonic structure is not complete until at least seven years of age. Furthermore, as with language, acquisition of musical structure occurs without formal musical training, but simply through everyday experience with music. This brings me back to my point regarding the strength of the rhythmic impulse, that music is acquired from one’s surroundings and the society in which one lives, and to write and play music that reflects those surroundings is both natural and likely to evoke a response from other members of that society.

As to Bartók, he may well have lived in Budapest, but he spent a significant amount of his life travelling throughout Hungary, collecting folk music and researching its origins. He immersed himself in the music of rural Hungary and the way this emerged in his music was very organic indeed – he would have spent far more time listening to and analysing folk music than he ever would have spent listening to ersatz gypsy music or Viennese waltzes. He would also have spent a lot of time studying the music of classical composers such as Richard Strauss and I would contend that his music, reflecting as it does both of these worlds, classical and folk, absolutely reflects his musical surroundings.

With regard to music and American cultural imperialism – though the music that surrounds us now is the result of the penetration of all things American, not all of it is American per se, nor is it all music that is approved of by the American corporate/political machine – jazz still gets dismal treatment in the home of its birth. And besides there are many past instances of new and vital music forms emerging in the wake of imperialism – Flamenco is a musical by-product of the Moor’s conquest of Spain, and the Hindustani classical tradition of North India – one of the richest in the world – evolved as a direct consequence of the Moghul’s invasion of India and the engagement between the Arabic and Persian music of the invaders and the ancient Karnatic tradition of the invaded. The means of arrival of any music in society has nothing to do with whether that music can be put to creative use.

Regarding your suggestions of bias on my part against other music, let me say that though I consider myself a jazz musician, I was brought up on a musical diet of jazz from 1945 onwards and classical music from 1880 onwards and have no bias against the classical tradition. I love both of these traditions and in making a point about the direction of some contemporary classical music, a direction which I consider to be misguided, it does not automatically mean that I’m biased against the music as a whole.

As to making untenable assertions about jazz itself and ignoring ‘free jazz’, I did mention in the original article that I didn’t believe all music should be played over a groove, and I actually enjoy playing free jazz very much and have been involved with it on many occasions over the years. However, though there is a strong tradition of what is known as ‘free playing’ in jazz that stretches back over 40 years, it remains a minority strand within the body of jazz as a whole. Most jazz is still played over a constant pulse. Finally, even within jazz there are arguments as to what ‘free jazz’ really means, and bearing this in mind, as well as its minority status within the music, I didn’t feel it was germane to this particular discussion.

Sincerely,

Ronan

Dear Ronan,

As an unapologetic classical musician (with ears wide open to other musics) I’m frequently accused of ‘elitism’, yet I’d never use a phrase like ‘a direction which I consider to be misguided’ about any form of music (however much such thoughts might drift through my skull).

You assert that the rhythmic impulse of ‘music is acquired from one’s surroundings and the society in which one lives’ then conclude that ‘to write and play music that reflects those surroundings is both natural and likely to evoke a response from other members of that society’. One doesn’t need to contest these ideas to reject the further silent assumption that classical music, or any other highly evolved art form, must be ‘natural’ and must be premised on listeners’ adopting the line of least resistance for all time to come. This would tend to preclude any form of aesthetic dissidence or innovation of the kind that doesn’t evoke instant acceptance.

As for Bartók, it seems you have now evolved a new definition of ‘organic’, one that is at odds with the naturism of your position outlined above. It appears that if you ‘immerse’ yourself in something then your relationship to it is ‘organic’ – this is having it both ways! Bartók immersed himself in more folk music than the Hungarian sort, and in a great deal more classical music than the Austro-German sort (Richard Strauss) current in the Hungarian society of his time.

Of course ‘[t]he means of arrival of any music in society has nothing to do with whether that music can be put to creative use’, yet this is not the same thing as simply acquiescing in the ‘understood template’ it generates or imposes, whether or not this is in the interests of greater market acceptance. At a time when we are in the throes of a peculiarly virulent form of imperialism, the choice of aesthetic dissidence may well impose itself. Very few composers are so daft as to expect nonetheless to attain mass appeal, yet this doesn’t impinge on their right to having their work disseminated.

Finally, I never suggested that you are biased against any form of music, merely that you are ‘bias[ed] in favour of jazz’. And why wouldn’t you be?

All the best,

Raymond

Published on 1 January 2006

Raymond Deane is a composer, pianist, author and activist. Together with the violinist Nigel Kennedy, he is a cultural ambassador of Music Harvest, an organisation seeking to create 'a platform for cultural events and dialogue between internationals and Palestinians...'.