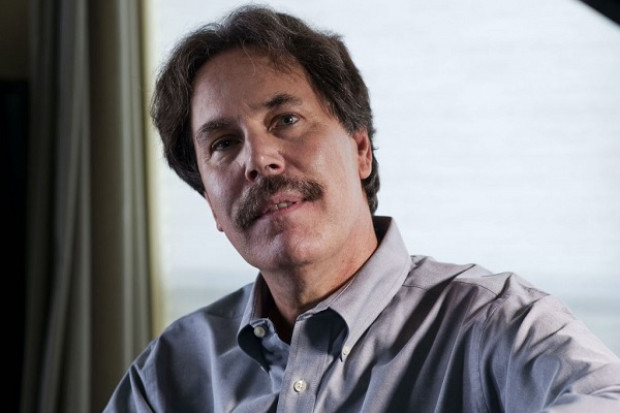

Tara Erraught (Photo: Mark Stedman).

Exploring Musical Life in Ireland in the 1700s

The title of the new release from the Irish Baroque Orchestra, their second in a series of five releases on Linn records exploring the Baroque period in Ireland, begs the question: The trials of who? Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci, as described in the album’s notes, was a larger-than-life soprano castrato active in Ireland in the latter half of the 18th century. The singer was something of a star in his day, developing friendships with major musical figures including J.C. Bach and a pupil in the young Mozart, and had a successful, if unorthodox, career. His trials, though, were nothing if not self-inflicted, largely a result of his decision to secretly marry his teenage pupil Dorothea Maunsell.

Tara Erraught takes Tenducci’s place in this release, with Peter Whelan directing the Irish Baroque Orchestra from the fortepiano. This is an album put together with a concert programmer’s eye, with a symphonic opener and orchestral works interluding the songs, as though to give the singer a break. At an hour and six minutes, it feels as if it treats the capacity of a CD as a target rather than a limit. But to an extent, this is music in costume, dressed up as a concert from 18th-century Dublin.

Irish connections

The Irish links are explored too in melodies borrowed by Johann Christian Fischer and Tommaso Giordani. The latter spent much of his life in Ireland, including at Smock Alley Theatre, where he served as musical director. Though ‘Caro mio ben’, a staple of the repertoire of Bartoli and Pavarotti, is probably his most famous work, Giordani incorporated many Gaelic melodies into other pieces, including the symphonic ‘Celebrated Overture and Irish Medley to The Island of Saints’.

Directed by Whelan, the Irish Baroque Orchestra sound terrific on the album, fizzing with life and energy, but it is in the two symphonic works – Giordani’s, and the Symphony in G major by Pierre van Maldere, both of which receive their world première recordings on this release – that the orchestra most gets to show off. The Maldere, which opens the album, is an enjoyable three-movement symphony, while the finale of Giordani’s provides a rollercoaster ride through a variety of Irish tunes that would likely be a crowd-pleaser even today.

Out of the ensemble, it’s Irish Baroque Orchestra’s first oboist Andreas Helm who spends the most time in the spotlight, not only with the solo part in the andante from Fischer’s seventh oboe concerto, a set of variations on the air ’Gramachree Molly’, but also providing the keening melodic line in the second movement of the Giordani overture (based on the Scottish folk song ‘Shepherds I Have Lost my Love’) and providing what amounts to a duet part with Tara Erraught in the J.C. Bach song ‘Ebben si vada – Io ti lascio’ and in that composer’s arrangement of the Scottish ‘Braes of Ballenden’.

The gift of Erraught

But what a gift we have in Erraught. Here is a singer who approaches every work with enthusiasm and generosity. She sings with ease through sometimes devilishly tricky passages, rapid, lengthy runs of notes, precisely controlled trills and messa di voce, all while seeming indefatigable. But she brings more than technique. There’s a palpable, infectious delight in her performances, whether she’s singing Puccini or Rossini or J.C. Bach.

Along with the Bach, the Giordani songs on the collection, ‘Caro mio ben’ and ‘Queen Mary’s Lamentation,’ allow Erraught and the ensemble to explore the more sensitive, reflective aspects of the music they’re performing. Under Whelan, the lamentation in particular achieves a wonderful effect, fading away to almost nothing in the closing bars.

Two songs from Arne’s opera Artaxerxes, written for Tenducci, serve as the opening numbers for Erraught. ‘Amid a thousand racking woes’ is a showcase of vocal agility, while the tuneful ‘Water parted from the sea’ is more tender and gentle. The castrato link exists in the closing work as well, Mozart’s madrigal ‘Exsultate jubilate’, which was written not for Tenducci (Mozart did write a song for Tenducci, though it’s lost), but for Venanzio Rauzzini. Like the Arne works at the opening, this work bubbles with life, while carrying its weight as a technical showcase.

There is a lot to unpack around the music written for castrati, around the culture that led to the castrato voice being so sought after in the classical period, and around the practice of castration in service to the arts, but that is beyond the remit of this review. Though in centring Tenducci, there is an extent to which the practice is centred as well, which the album’s subtitle, ‘A Castrato in Dublin’, reinforces. There ought not to be any pride or nostalgia for the custom. Luckily, the album also centres Tara Erraught, a phenomenal performer in her own right. Though she may be in costume as Tenducci, she makes this repertoire quite comfortably her own.

To purchase The Trials of Tenducci: A Castrato in Ireland, visit https://www.irishbaroqueorchestra.com/shop.

Published on 31 March 2021

Brendan Finan is a teacher and writer. Visit www.brendanfinan.net.