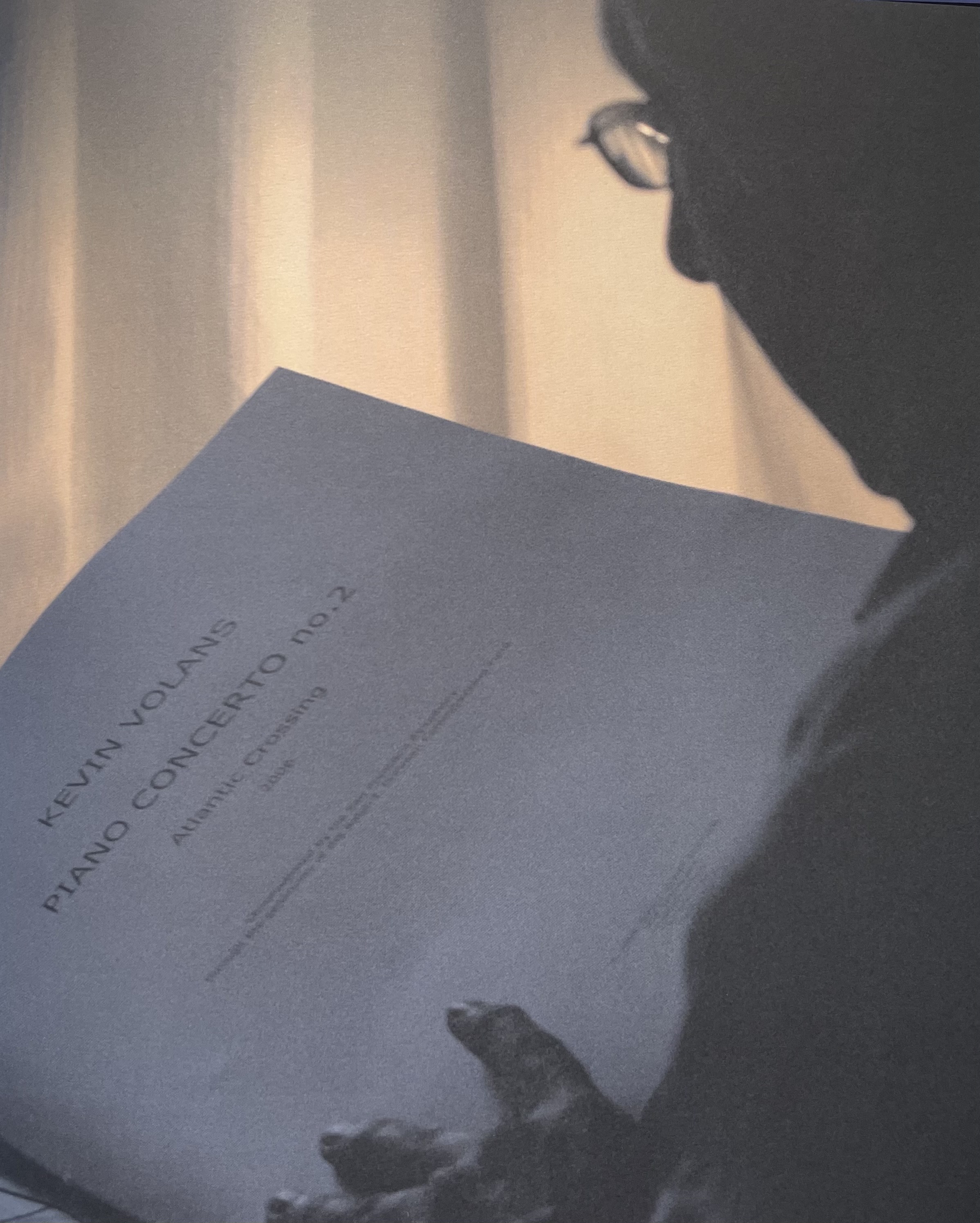

Composer Kevin Volans with a score at his home in Knockmaroon, Dublin, in October 2006. Photo © Lucy Clarke

Wild Air: The Music of Kevin Volans

‘In composing and in life in general there’s only one subject worth pursuing, and that is freedom. Freedom not only from other people’s restrictions but freedom from your own baggage’. Kevin Volans is talking to me about the primary subject in his work, the basic tenet that underlies everything he does. ‘It always involves overcoming, because you’re always trying to throw out’. Freedom, that most elusive of human desires, has always seemed to me a chimera, a scary product of the liberal imagination, something that can never be real and would be too frightening to contemplate if it were. But I want to understand what he means by freedom, because I feel I hear something equivalent in his music: a sense of wide horizons, of open spaces filled (to use one of his recent titles) with ‘wild air’.

Volans has changed since I first met him in Belfast seventeen years ago. He seems more… mellow? Perhaps: I suspect not always. Generally ‘less uptight’, by his own admission. Happier? We’d have to define happiness. Watching him prepare a mouth-watering South African lamb recipe in his kitchen in Knockmaroon I feel very glad to be in his company: this is a man I admire enormously, one of the most gifted composers of his immensely brilliant generation. For a time his second string quartet, Hunting: Gathering, was one of my favourite pieces of music. In the past year I’ve listened to his sixth string quartet 27 times (so my Play Count informs me). Since our first meeting all those years ago he has written hours and hours of music – some of the most ravishingly beautiful, perplexingly empty, genuinely contemporary music I know. And, we mustn’t forget: Kevin Volans is Irish. Sort of.

He was born in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, in 1949. As a teenager his twin loves were art and music. At the age of thirteen he was creating quasi-Abstract Expressionist canvasses in his parents’ garage, black and white paintings inspired by Franz Kline. Only a few years later he was already an accomplished pianist; he gave his first broadcast recitals (Liszt, Chopin, Messiaen) at the age of twenty-one. He came to Germany in 1973 to study with Karlheinz Stockhausen and made his home in Köln, one of the great centres of avant-garde music, a hotbed of activity, attitude-mongering and general snobbishness. In 1986 he was appointed Composer-in-Residence at Queen’s University, Belfast, on a three-year contract. When it ran out he moved for a while to Donegal before settling in Dublin. He took Irish citizenship in 1994.

I know Volans well enough to be aware that questions about nationality are not among his favourites. When he was growing up in South Africa, he tells me, white people thought of themselves as Europeans. When he came to study in Köln he realised quite clearly that he didn’t feel European at all. Returning to South Africa, he discovered he wasn’t really African. To Volans, categories such as ‘South African composer’ or ‘Irish composer’ are unacceptably simplistic and meaningless: they reduce the world. Identity has little to do with place: analogously, meaning in the arts has little to do with style. Overcoming the issue of style in music became the first stage in Volans’ pursuit of freedom.

Overcoming Style …

The new music scene in Germany in the 1970s was obsessed with style, but in an utterly prescriptive – indeed proscriptive – way. Stockhausen’s students were not allowed to write tonal music; they weren’t even allowed to write octaves, because they created an unwanted emphasis on one pitch over another and thereby gave the impression of a tonal centre. ‘I remember Richard Toop [Stockhausen’s teaching assistant] telling us, “no prettiness!” Stockhausen couldn’t stand incompleteness, and insisted we work through all the possibilities of our material. He told us, “If you don’t use all possibilities you are merely a mannerist”. He gave us all this feeling of serial guilt’. And so a rebellious streak set in: ‘my whole mission in the later 70s was about overcoming dogma and style – how to write music that was not restricted by the idea of what new music was supposed to sound like’.

The music written by Volans and several others around Köln at that time (renegade Stockhausen students like Walter Zimmermann, and others like Chris Newman and Michael von Biel) has since become known as the New Simplicity. Oddly, in a way, as the music is not exactly simple: Volans’ Monkey Music (1976) is a virtuoso piano piece. The point was that simplicity was no longer forbidden – neither was tonality, or metric rhythm, or quotation or paraphrase of other music. These composers refused to make style the arbiter of value. They no longer believed the ‘historicist dogma’ that music evolves in a straight line, and that there are acceptable and unacceptable ways of composing. Some musicologists today regard the New Simplicity as the beginnings of postmodernism in music.

Central to this phase of Volans’ work was his involvement with African music. He made several trips back to South Africa during his years in Köln, recording the music and the natural sounds of his homeland. Listening to his tapes in his apartment in Germany, he found the perfect antidote to the restrictive atmosphere of the Köln new music world. He wanted to integrate African music into his composing, not its sound but its essence – the way it unfolds in time, the relationships between the musicians in an ensemble, its open-ended quality. So began his interest, which continues to the present day, of composing non-conceptually, and a new obsession: with overcoming form. ‘I was interested first in overcoming style and then in overcoming form’, he tells me. ‘That’s why I was interested in African music, because it was a kind of music that had no perception of form, no perception of time as we know it, no guilt about change, was free from guilt. In the 70s we had serial guilt, and then in the 80s it was guilt about change, an anxiety about change; the minute a piece of music started you felt it had to change. In African music that feeling doesn’t exist. I was interested in trying to write music that was in a sense formless.’

What does it mean to say that African music has no perception of form? There is nothing pejorative about the idea, rather an acknowledgement that traditional African musicians think about what they play quite differently than do westerners. The ethnomusicologist John Blacking, a colleague of Volans in Belfast in the late 1980s, insisted that what sounds to the western ear like repeating patterns in much African drum or xylophone music is perceived by an African ear as a continuous flowing movement like a waterfall, not divisible into repeated motifs. The challenge Volans took on was to compose non-conceptually, without the preplanning so beloved of Stockhausen, and to allow his pieces to be open-ended. One of the most gorgeous results is Matepe (1982) for two harpsichords (tuned to an African scale) and rattles; the form of the piece is created spontaneously by the musicians as they play, by freely choosing how many times they want to repeat material, or which of the notated patterns they want to combine together at any given moment. The rhythms in the harpsichord parts interlock from start to finish, a technique that requires a good deal of practice; you have to think yourself out of a western rhythmic grid and allow the longer African phrase lengths, with their shifting downbeats, to seep in. The effect, once you master it, is vertiginous – a sort of ecstasy, like discovering you can dance after years of thinking you could only pogo.

One of the most powerful works of these years is White Man Sleeps, originally written in Durban in 1982 for the combination of two harpsichords, viola da gamba and rattles, and rewritten in 1984 for string quartet. It is also, thanks to performances and recordings by the Kronos Quartet, Volans’ best-known piece, far outstripping the narrow confines of the new-music ghetto. Choreographers the world over, starting with Siobhan Davies, have fallen in love with it, and in 1992 the Kronos recording (on their CD Pieces of Africa) spent twenty-six weeks at the top of the classical and world music charts. It is a hard heart that would not be melted by the exquisite fourth movement, based on patterns from Nyungwe panpipe music from Mozambique, with a freely composed viola melody floating above it (and yet weirdly bringing to mind, as Volans perceptively notes, Schubert and the Biedermeier world of early nineteenth-century Vienna: ah, the mysteries of music). And yet at some point in our acquaintance with White Man Sleeps most of us experience uncomfortable twitches – is the appropriation of African music in this score entirely, you know, lacking in exploitation? Isn’t there a ghost of cultural imperialism behind the whole idea of reworking African music for string quartet?

In retrospect, works like Matepe, White Man Sleeps and the percussion solo She Who Sleeps With A Small Blanket (1985) seem to have much more to do with the new-music world of the early 1980s than they do with the state of African music at that time. They are attempts to reconcile African and European aesthetics, to offer musical models of a multicultural society. Elements of different traditions are respected, shared, and, in coming together, are allowed to generate new meanings. There is a clear political point to these pieces: a protest against the barbaric philosophy of ‘separate development’ for whites and blacks in Volans’ homeland, and a wish for each to be involved creatively in the other’s culture. ‘I think this was not understood at the time’, he says. ‘I thought of these pieces as a new music of southern Africa, or music for a new South Africa’. This phase of his work continued, although with interruptions for other sorts of work, up to his fifth string quartet, Dancers on a Plane, in 1993: by then, he says, he felt ‘the moment for this kind of work had passed, along with the apartheid state’.

Composer Kevin Volans handstitching a score in his house in Knockmaroon, Dublin, in October 2006. Photo © Lucy Clarke

…and overcoming form

While his interest in African music had been intimately connected to the desire to overcome form in music, there were other sources that fed this same drive in the 1980s and 90s. One was Volans’ continuing interest in the visual-art world, where discussions about form seemed much more advanced than the parallel discussions in music. Another was his close friendship with the American composer Morton Feldman, whom he got to know while still living in Germany. In Feldman, twenty-three years his senior, Volans recognised immediately a kindred spirit. Feldman ‘came along saying exactly what I believed: never judge a work from the point of view of style.’ And whereas Stockhausen was the arch-architect in music, obsessed with questions of form, Feldman was turning the whole subject of form on its head. ‘Feldman would say things like: “I’m not interested in timing, I’m interested in time,”’ recalls Volans. ‘And part of my interest in African music was precisely that, that they had a totally different perception of time.’ Feldman’s compositions of the 1980s pushed beyond the twenty-minute piece so characteristic of the new-music world into very long time spans, in some cases writing pieces that lasted four or five hours without pause: in this exploded time-space, questions of form became essentially irrelevant. And while Volans didn’t follow him down that line, there were ramifications in his own music. The string quartet Hunting: Gathering (1987) consists of a great many different musical ‘fragments’, invented, quoted, or paraphrased, set beside each other with no causal linking principle. The open-ended feeling of Matepe is recreated here: the piece feels like a walk through an imaginary landscape with no particular goal in mind. This is amazing music, not really ‘African’ and not really ‘European’; you feel the very terms melting away as you listen, like the melting watches in Dalí’s famous painting. Each time I’ve heard Hunting: Gathering I haven’t wanted it to end. Maybe the composer hasn’t either, as the piece is cut off part-way through a musical phrase that hasn’t actually finished.

The obsession with overcoming form persists in the third string quartet, The Songlines, written in 1988 and inspired by the novel of that name by Volans’ close friend Bruce Chatwin. ‘After a performance of the third quartet a critic complained that I had a “form problem”’, Volans tells me. ‘She didn’t see a formal structure. I took it as a compliment.’ The same quality characterises the ravishing One Hundred Frames, written for the Ulster Orchestra in 1990; and his opera, The Man with Footsoles of Wind, which is partly about the nature of time in the late twentieth century. He worked a lot in the 1990s with dance, partly because of the possibilities it offered him in terms of form: ‘it freed me from the necessity of filling everything in, like a child’s colouring book. It influenced the way I thought about composing, that a piece could be very fragmentary and have gaps in it.’ In collaborating with Siobhan Davies he found that both he and she had to learn to ‘shut up’ at times, to give the other’s art form space. ‘The dancers sometimes complained that they got disoriented and didn’t know where they were. I thought that was a kind of success as well.’

‘No composition’

For me a new phase of Volans’ work begins with Cicada for two pianos, written in 1994, and one of the key works in his output to date. I remember how shocking it was at the time to hear Volans say that this was his ‘first genuinely minimalist piece’ – by the mid-90s most of us thought minimalism was a spent force. But the music itself, while indeed dependent on repetition, is abundantly alive and new: gentle, luscious, with harmonies that at the outset seem slightly sour (a Bb major chord with a few added notes) but that suddenly become warmer, indeed luxuriant, with very little apparently having changed. As in Matepe the pianos’ rhythms interlock from the first bar to the last. But the performative difficulties are compounded by Volans’ use of subtle shadings of tempo: the two pianos play a phrase several times at quarter-note equals 132, then – both together – they shift gear to quarter-note equals 126, then down again to 112, then to something else again. At first it seems impossible, but it’s not. And one mustn’t forget the most important feature of all: touch. In Cicada everything depends on touch – not just loud and soft, but the voicings of the notes in the chord, the curves of the phrases. It is this aspect of performance that determines whether the music will seem interminably repetitive or ‘like an orgasm’ (as a female friend of mine described it).

The title Cicada is borrowed from a painting by Jasper Johns (which has nothing obvious to do with the insect), but the real inspiration, Volans says, came from an exhibition in Kilkenny of works by the American artist James Turrell. The piece that particularly fired his imagination was ‘a sky piece’ – a large box of a building with a square cut in the roof revealing the sky. ‘We sat in a large cubic light box in the grounds of a castle and over a period of an hour watched a square of sky overhead turn from the blue-grey of Irish clouds though Yves Klein blue to slate black. I stayed overnight in a friend’s minimalist house in Killiney. The next morning I woke to a glittering square of sunlight reflected off the sea and I decided: no composition; don’t change anything except the tone.’

This experience was a pivotal one for Volans, and pushed him in a direction he has been exploring ever since. Put into words, it seems like the ultimate reductio ad absurdam: overcoming composition. ‘I thought, I’ve tried to get rid of style, then form, how about trying to get rid of content?’ he says, with a smile that only shows how serious he is. ‘Looking back at the end of the millennium I was astonished how busy most music of the twentieth century is. It’s true of Schoenberg, Stockhausen, or Steve Reich. Busyness, and being seen to be busy – I got very cynical about this. And I thought: this is ridiculous. What would happen if we tried to eliminate content in music altogether? Now people have done it, like La Monte Young; Phill Niblock has these very minimal pieces, but in fact it’s a hugely complex sound. But I haven’t done it. So let’s try it. So I tried to write these drastically reduced pieces. I love the kind of visual art which is just three lines around the edge of the canvas or something; and I thought, why can’t we do this in music and really make it work?’

One of the pieces that best exemplifies this new tendency is his String Quartet no.6, written for the Duke Quartet in 2000. (The work is actually for double quartet, the second either live or pre-recorded.) The piece gently rocks between two chords for much of its twenty-five minutes – but in a way the two are overlapping parts of one larger chord, so there is in this sense no real change of harmony at all. Very occasional solo phrases and longer-than-expected silences clear the air from time to time; but we keep coming back to the chord. This is very courageous music – courageous because Volans makes no pretence at being ‘interesting’ or ‘clever’ and is not afraid to let the music be ‘empty’. To me it’s one of the most fantastic pieces in the recent string quartet repertory. ‘I wanted it to be like a really good massage’, he says, and for that reason originally planned to write 55 minutes (massages are usually an hour, apparently, including five minutes to get dressed). The commissioners talked him down to roughly half that length. ‘It was written for a lunchtime concert in the City of London. I thought these people should come in, and have 55 minutes of therapy, and then go back to their offices!’ Here again, as in Cicada, tone is everything: subtle changes of colour, rather than harmonic movement, are the essence of the music.

He lights up when I mention the word colour. ‘I think it’s really important as a composer that you get the colour right. I discovered this in trying to do those African pieces, that the colour influenced the meaning of the music as profoundly as the pitches. This issue has been talked about a lot and given a lot of lip service, but in fact if anyone criticises you it’s always because of your pitch structure, and he or she completely ignores the colour. In the case of my sixth quartet, I was thinking of a certain colour, a sort of silvery blue – that’s what I wanted. And I came across that chord’ – the chord that opens the piece, and stays there most of the time – ‘and decided that was the right colour’. By colour he means both harmonic and timbral colour; in contexts such as his String Quartet no.6 the two are inseparable. ‘If you choose the right colour’, he adds, ‘then you’ve got the whole piece.’

This is close to what he means by overcoming composition. Not freedom from content, as that’s not possible, but freedom from ‘content’. His search for several years now has been to find ways of writing music that don’t involve ‘composition’ at all. Volans himself is the first to admit that this quest is, in some sense, an illusion. Does it matter? It seems to fire his imagination. ‘There’s a comment that Philip Guston made’, he says: “I think the artist should not want to be right.” I think that’s wonderful’. Given that his wish to free himself from content has usually led to a great reduction in material, his exuberant Trio Concerto (2005) for violin, cello, piano and orchestra, which, he calculates, ‘has 80,000-plus notes in it’, might seem like an anomaly. But it’s not really: ‘the idea was that it was just a barrage of sound and in a sense it had no content because there was so much happening’.

Volans has always been a controversial figure, right from the beginning of his career – when he was blacklisted by the broadcasting networks in South Africa because of his involvement with African music – to the present. (Ironically he is being rediscovered in South Africa now.) His recent work has puzzled some musicians as much as it has delighted others. ‘I was commissioned to do a piece for the BBC Symphony Orchestra’, he tells me, ‘and I had this idea of a double concerto – simply splitting the orchestra down the middle and bouncing a chord from one orchestra to the other, but it’s the same chord for nearly the entire piece. The conductor hated it. It was a huge scandal. It was one of the worst experiences of my life. I was very ill afterwards as a result. I’d worked so hard at the orchestration, which was incredibly difficult to bring off: the whole piece is about the beginning and ending of the chord’. The work in question, the Concerto for Double Orchestra (2001) strikes me (judging from the MIDI version; he won’t play me the recording of the premiere) as Volans at his best. It seems that some of us are going to need time to assimilate his recent work.

Volans’ most direct impact on the Irish musical scene has been in the role of teacher. The list of young composers who’ve studied with him in various capacities is colossally impressive (‘and in some cases they’ve won prizes after they’ve studied with me’, he points out with a smile): Elaine Agnew, Deirdre Gribbin, Andrew Hamilton, Deirdre McKay, John McLachlan, Simon O’Connor, Jürgen Simpson, Jenny Walshe. And that’s just for starters. ‘And officially Gerald Barry’, he laughs, ‘though he’d kill me for saying so!’ One of the aforementioned composers once described Volans to me as a natural teacher. And you get the feeling he likes it. ‘Certainly in teaching I’ve learned a lot from my students. I didn’t teach Jürgen, for example, all that much but he was my assistant for a time, and we exchanged ideas. I’ve been very stimulated by some of their interests, and the kinds of music they’ve forced me to listen to. So it’s been a two-way exchange. And it certainly has made me feel welcome in the country.’

After spending much of the later 1990s involved with dance, most of his commissions now come from the orchestra world. A new piano concerto, his second, will have its premiere in San Francisco this November; and he is beginning work on a percussion concerto. Chimeric or not, there are new freedoms that continue to entice him. ‘Basically I think now I’m trying to write guiltlessly. Really without guilt. It’s a hard thing to do’. He has sometimes spoken about composing and feeling that Morton Feldman was watching over his shoulder, acting as his disembodied conscience. ‘That’s what I mean about writing guiltlessly. I feel this very strongly – you can’t live your life looking over your shoulder. That’s what stifles true creativity. Even Feldman – I mean, I adored the man, but Feldman was part of a macho crowd, the big boys of art. They definitely competed with each other – and he cornered the market in long pieces. I thought, we’ve got to get rid of this too – Feldman guilt! I suppose what I’m also trying to point to is the idea of overcoming testosterone. You don’t have to prove anything.’ In Kevin Volans’ case there’s not much left to prove.

On CD

While he is generally well represented on CD (not forgetting the best-selling Nonesuch discs by the Kronos Quartet, White Man Sleeps and Pieces of Africa), too few of Volans’ recent works are yet available. There are a few exceptions: Cicada for two pianos is available on Black Box BBM1029; the Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments and Untitled (in memoriam G.H.V.) is available on Chandos 9563, the latter featuring Volans himself as piano soloist; and his String Quartet no.6, in a superb performance by the Duke Quartet (coupled with his first two quartets, White Man Sleeps and Hunting: Gathering) is available on Black Box BBM1069. Check out, too, the great arrangement of White Man Sleeps by the Dublin Guitar Quartet on Deleted Pieces, Greyslate Records CD014).

Published on 1 November 2006

Bob Gilmore (1961–2015) was a musicologist, educator and keyboard player. Born in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland, he studied at York University, Queen's University Belfast, and at the University of California. His books include Harry Partch: a biography (Yale University Press, 1998) and Ben Johnston: Maximum Clarity and other writings on music (University of Illinois Press, 2006), both of which were recipients of the Deems Taylor Award from ASCAP. He wrote extensively on the American experimental tradition, microtonal music and spectral music, including the work of such figures as James Tenney, Horațiu Rădulescu, Claude Vivier, and Frank Denyer. Bob Gilmore taught at Queens University, Belfast, Dartington College of Arts, Brunel University in London, and was a Research Fellow at the Orpheus Institute in Ghent. He was the founder, director and keyboard player of Trio Scordatura, an Amsterdam-based ensemble dedicated to the performance of microtonal music, and for the year 2014 was the Editor of Tempo, a quarterly journal of new music. His biography of French-Canadian composer Claude Vivier was published by University of Rochester Press in June 2014. Between 2005 and 2012, Bob Gilmore published several articles in The Journal of Music.