Mick O'Brien, Emer Mayock and Aoife Ní Bhriain

Tunes from Famine Times

One of the continuing interests of many traditional musicians is the exploration of historical publications and collections for ‘new’ old material. On this CD, More Tunes from the Goodman Manuscripts, Mick O’Brien (uilleann pipes, flute and whistle), Emer Mayock (uilleann pipes, flute and whistle), and Aoife Ní Bhriain (fiddle, viola and concertina) return to the Goodman collection eight years after their initial foray into this substantial body of tunes, which was awarded a Gradam Ceoil in 2014.

From Dingle in Kerry, Canon James Goodman (1828–96) collected and compiled tunes and songs from a range of sources, most notably from the uilleann piper Tom Kennedy, a blind piper who was active in the Dingle peninsula. Goodman, who was Professor of Irish at Trinity College from 1879, was a piper himself, and this, coupled with his knowledge of Irish, has led to the collection being held in high regard. Despite this, it remained unpublished for many years, until a selection appeared in Hugh Shields’ Tunes of the Munster Pipers (1998). A second gleaning from the manuscripts (edited by Hugh and Lisa Shields) was issued in 2013, and this was the main source for this recording. However, thanks to the efforts of the Irish Traditional Music Archive and the Library of Trinity College, Dublin, the entire collection has been digitised and is freely accessible for browsing – a truly fantastic and fascinating resource to have at one’s fingertips. And although anyone can now access these manuscripts themselves, these types of recordings retain a crucial function as re-translations or re-mediations for the broader traditional community, especially for players who may not have the knack of re-animating tunes from the calcification of preservation.

Given the timeframe in which Goodman’s collection was made (c. 1840–1866), this recording allows us a window back into the soundscape of mid-nineteenth century Ireland. It wisely doesn’t try to imagine a ‘historically informed performance’ style of that period – our knowledge of how these tunes might have been played is too sketchy for this. Yet at the same time we have some connection with these decades, as the Galway piper Dinny Delaney and Tipperary fiddler Edward Cronin grew up in this period, and their few recordings are highly regarded today. The one nod towards an earlier style might be the absence of any accompaniment instruments on the album, although the uilleann pipes’ drones are used frequently under the fiddle and flute (as on the opening set of reels), and there are some fiddle and viola drones and accompaniments too (often on the slower tunes).

Families of tunes

Some of the tunes included are very similar to those in circulation today: ‘Lady O’Brien’ is basically ‘The Honeymoon’ reel; ‘Coffee and Tea’ belongs to the ‘Connie the Soldier’ and ‘Southwest Wind’ family of jigs; and ‘O’Sullivan’s Fancy’ adds yet another second strain to the familiar jig ‘Have a Drink on Me’. Those familiar with the first blush of recordings and performances from the Goodman collection will perhaps have fond memories of ‘The Ladies’ Cup of Tea’, one of the tunes which has been most taken up by musicians in the past decade; the gender-neutral equivalent here is equally flavoursome (‘The Cup of Tea’ is not the usual session warhorse but the ‘Copperplate’ in disguise). Other tunes like ‘The Aberdeen Reel’ and ‘The Kerry Lassie’ are more unusual and don’t seem to be found outside the manuscript collection. The album finishes with a tune, ‘The Black Joke’ (coupled with ‘Split the Whisker’), whose popularity as a ribald song was probably at its height in the eighteenth century, but which is rarely heard today.

The most striking material here lies outside the quotidian dance-music repertoire. There is an unusual version of ‘The Eagle’s Whistle’, the famous march associated with the O’Donovans of Limerick. A glance at the manuscript (Goodman seemingly copied this from the Pigot manuscripts; this itself was a copy of an original manuscript lent to John Edward Pigot by Mrs Woodruffe of Cork) shows how a recording can smooth out problems in the notation: the tune is written with the long notes on the second beat (they generally are played on the first beat). However, the trio sensibly follow the rhythm of the usual version – in fact it’s almost impossible to try to play it and keep the emphasis off the longer notes! The manuscript does throw up a second quandary, as the last part of the tune is grouped in 6/8 time; on the recording this has been reworked to keep with the original 3/4 time signature. Maybe I’m missing an additional source, but it is a curious re-writing, and it would be intriguing to see how playing this part in a 6/8 rhythm might change the shape of the tune.

Harp-like phrasing

The highlight of the album for me was encountering ‘Humours of Glynn’, which shares its name with a piping piece ascribed to Pierce Power, an eighteenth-century gentleman piper. Despite some similarities to the piping piece, this is a much more substantial four-part tune, and almost harp-like in some of its phrasing. It’s worthwhile to consult the manuscript version again here, as the end of the second and fourth parts of the tune were mistakenly altered in the 2013 published version (as detailed on the fantastically thorough ITMA Goodman website): in fact all four parts in the manuscript end on the same note (A in the original). It’s a minor detail though, and doesn’t detract from the depth of feeling that the musicians wring from this plangent air. The decision to play this and tunes like ‘Ceann Dubh Dileas’ as single performances allows the elegance of the tunes to be appreciated, and in the latter, the repetition of just these eight bars becomes almost incantation-like.

The project as a whole raises some wider questions about how we might consider the ‘authenticity’ of the printed sources of the manuscript, and the natural way that musicians might editorialise through praxis. There are lots of examples on the recording: for instance, the ‘scotch snaps’ in the first part of ‘The Cup of Tea’ have been ignored (these are common in older manuscripts and publications, reminders of the Scottish origins of many of these tunes), and an unusual rhythm in the second part of ‘Coffee and Tea’ is regularised. Thanks to the digitisation of the original sources, any listener with a computer and an internet connection can peruse the manuscripts for themselves to find their own examples. But while this sort of forensic examination is fascinating and diverting, there is the risk of getting bogged down in details, and being distracted from an appreciation for the album as a whole. Which is to say that the music is beautifully recorded here; the instruments sound crisp and bright, and the exceptional and enthusiastic performances of O’Brien, Mayock and Ní Bhriain instil these tunes with new vigour and spirit. What might have been a dry exercise of melodic excavation is transformed into art through the consummate taste and subtle interpretation of the musicians. It will bring these tunes to the attention of many musicians, and might increase the traffic to the Goodman Manuscripts site, but above all this is a rich and magnificent collection of music in its own right, and deserves a wide listenership.

To purchase More Tunes from the Goodman Manuscripts by Mick O’Brien, Emer Mayock and Aoife Ní Bhriain, visit https://goodmantunestrio.bandcamp.com.

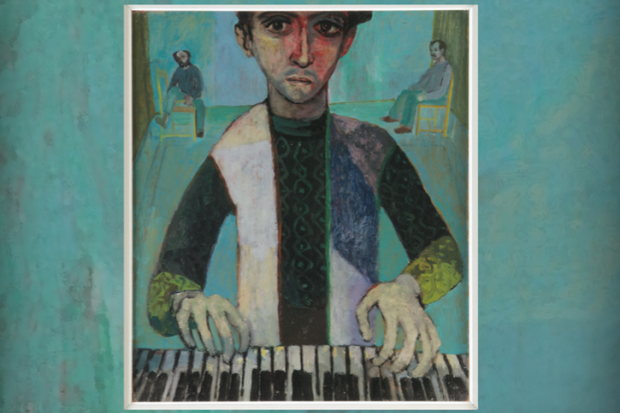

Click on the image below to listen to the first track, ‘Johnny is gone to France’, ‘Highlanderʼs Kneebuckle’ and ‘Lady OʼBrien.’

Listen below to an interview with Emer Mayock about the Goodman collection on Culture File on RTÉ Lyric FM.

Published on 11 February 2021

Adrian Scahill is a lecturer in traditional music at Maynooth University.