Rafael Payare and the Ulster Orchestra performing at the BBC Proms in 2016.

A Story of Resilience

Any regular reader of the Belfast Telegraph will be familiar with the writing of Alf McCreary; long-time correspondent for the paper and current Religion Correspondent; MBE and recipient of numerous journalism awards. Now in his 80th year, McCreary has been writing about the Ulster Orchestra for over fifty years and recently published Unfinished Symphony: The Story of the Ulster Orchestra to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the orchestra. As a young, green reporter, he had only worked at the Belfast Telegraph for a couple of years before the orchestra started in 1966 under conductor Maurice Miles with violinist János Fürst as leader. If you are not familiar with either the Belfast Telegraph or Alf McCreary you will definitely have heard about Belfast in the 1960s. However, the circumstances around the birth of the orchestra are probably not as well known.

Unfinished Symphony is an illustrated history of the Ulster Orchestra, laid out in chronological order, and steeped in detailed information about its principal conductors, managers, CEOs, plus the politics and boardroom affairs. The orchestra was developed by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland under the then chairman, Captain Peter Montgomery, who was passionate about the establishment of the new group. Maurice Miles, conductor of the City of Belfast Orchestra and the Belfast Philharmonic Society since 1955, was drafted in as Principal Conductor. What is striking in considering this monumental development in the arts is where it sat in the context of the political and social developments taking place at the time. The book points out that during the same period, the swinging 60s, Van Morrison released ‘Brown Eyed Girl’, but trouble was just around the corner. McCreary reminds us of the sharp focus of political activity in Belfast: 1966 saw Loyalists led by Ian Paisley in the ascendancy and the loyalist group the UVF killing three people in the city. This was the start, McCreary writes, of a ‘forty years revolution … with no prospect of a stable outcome, even at this time of writing.’

In its inaugural season the Ulster Orchestra played 13 concerts in what was (and still is, according to many of the interviewees McCreary spoke to) one of the best concert Halls in Europe: The Ulster Hall. Venezuelan conductor Rafael Payare, who was with the orchestra between 2014 and 2019, recalls in his interview with McCreary that the acoustic was ‘better than any concert hall in London.’ This must surely have had a very positive influence on the success of the orchestra.

The tumbling of society

In the years immediately following its establishment, the orchestra’s concerts in the Ulster Hall were receiving only small audiences of around 350 – a quarter of the capacity. The orchestra had no option but to ‘proceed as normal’ in what were increasingly unpredictable and violent times. McCreary again reminds us that in 1968/69 the civil rights movement and the formation of the Provisional IRA led to conflicts and murder over the following years in what he describes as ‘…the tumbling of society into widespread violence…’. The orchestra’s manager during the 1972–73 season, Malcolm Ruthven, summarised something crucial about how the orchestra was to navigate the next forty years: ‘The Orchestra believed that it had a moral obligation to continue its plans and contribute to the support of a quality of life that was fast fading.’

Perhaps because of this, and also because the orchestra didn’t initially receive critical acclaim, it soon became apparent that they were living beyond their means; ultimately it was proposed that the Ulster Orchestra merge with the BBC Northern Ireland Orchestra. The proposals were met with much resistance on both sides, but without this compromise all Northern Ireland orchestras faced redundancies. By 1981, the result was a much larger, independent Ulster Orchestra of 55 members (35 when it started) under chairman Stratton Mills. He formed an impressive board with 17 directors including councillors, lawyers, BBC executives and Arts Council of Northern Ireland representatives who drove the orchestra and, crucially, were able to engage in substantial fundraising. They secured a major sponsorship deal from Gallaghers of Belfast – the largest tobacco factory in the world. These were radically different times.

Music and soloists

Until a quarter of the way through Unfinished Symphony, there is no mention of the music actually performed, apart from references to the fact that the orchestra had now attained a high standard. We know that it had been performing in the Ulster Hall and the Sir William Whitla Hall at Queen’s University. It is obvious, however, reading between the lines, that in working with stand-out names like Vernon Handley, Mstislav Rostropovich, Yan Pascal Tortelier, Sir James Galway, Barry Douglas, Tasmin Little and Jaqueline du Pré, the orchestra was of the very highest standard. In 1985 it performed its first BBC Prom in a hefty programme including Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 2 with soloist Barry Douglas. This was to be Principal Conductor Bryden Thomson’s last big concert and he was replaced by Vernon Handley; after eight remarkable years, Thomson was hurt to have been let go.

The book later explores certain elements of the history of the orchestra, featuring interviews with, amongst others, Harold Wilkin, board member of the orchestra; Colin Fleming, Principal Flautist; Catherine Handley, widow of Vernon Handley; Yan Pascal Tortelier, and Sir James Galway. Handley’s son Patrick also recalls his father’s love for Belfast:

My father loathed bullying, and he was physically a surprisingly brave man. Nothing would deter him from going to Belfast… knowing that he was conducting musicians from all sides… was to him very symbolic. Dad liked the quietly subversive nature of this.

The introduction of these new voices into the narrative gives some relief from the factual, political, corporate and financial information, although the turbulent political times also constantly demand our attention.

Tours and conductors

The Ulster Orchestra had undertaken many overseas tours by 2001, which were ambassadorial roles as much as musical ones. In 2001 they were booked for a USA tour on a trade mission and cultural visit. The tour was booked for October, but on 11 September 2001 things changed forever. The orchestra’s tour was now under huge pressure. McCreary travelled with the group to America from Shannon airport. This is a chilling read, especially from the point of view of McCreary, who only a few weeks before had spent a lovely sunny afternoon at the top of the World Trade Center with his son. The orchestra performed in the City College, Harlem, and the introductory speech given by Michael McGimpsey, Northern Ireland’s Minister for Culture, underlined the fact that as a person from the North, he ‘fully understood the suffering of the people of New York’. They played Mendelssohn’s second symphony, which references the sorrows of death.

Today, the Ulster Orchestra has an extensive education and community outreach programme. One of the school programmes was the Pied Piper in which 200 school children dressed as rats, formed a choir and performed with the orchestra. This production was awarded the Inspire Mark of the 2021 Cultural Olympiad and led to the appointment of Brian Irvine as Associate Composer. This in turn led to a series of exceptional large-scale community projects such as Rain Falling Up, which was shortlisted for a British Composer Award.

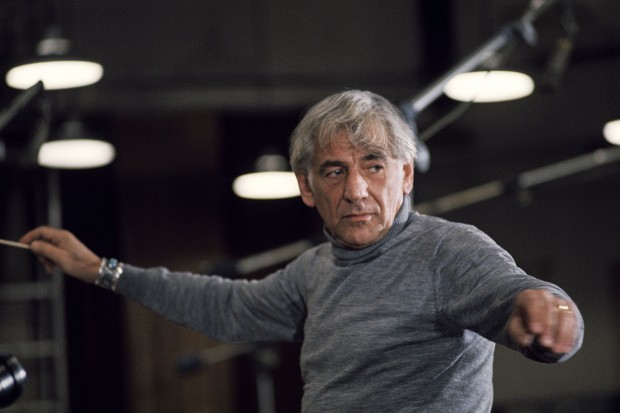

In 2011 the orchestra also made history when JoAnn Falletta was appointed as Principal Conductor (2011–2014). She became the first woman and first American to hold the position. Falletta had studied under Leonard Bernstein and went on to have a stellar career internationally. She says about Belfast:

…this is a place which is opening itself up to the world. It is like a flower blossoming and I am glad that the Ulster Orchestra is playing a part in this and will continue to do so, after all the long years of the Troubles, when it was one of the stalwarts in keeping music alive here.

Former CEO Dr Rosa Solinas recalls the appointment of Rafael Payare as Principal Conductor. ‘His appointment was a master stroke in the development of the orchestra.’ His tenure culminated in a BBC proms concert in 2019 with Beethoven’s and Shostakovich’s first symphonies. The appointment of Daniele Rustioni in 2019 further cemented the Ulster Orchestra’s place as one of the top orchestras.

There is an astonishing amount of detailed information in McCreary’s book, and he continues through board chairmen, principal conductors, funding issues, the Save the Ulster Orchestra Campaign in 2014, and, as usual, funding issues dominate the outlook for the future of the orchestra. However, Richard Wigley, the current Managing Director, said shortly after his appointment that the orchestra’s structures and policies, put in place over the last ten years, seem to have led to a successful progression out of some uncertain years to a promising future, reflected in box office, community engagement and sponsorships.

… how did we manage to survive on half of the money of other symphony orchestras? We survived because of our resilience and we became ever more efficient, and I’m not sure that this has been properly recognised.

Resilience

McCreary’s award-winning journalism might not be the most striking feature of this book. What stands out is the impressive amount of historical research into the orchestra’s records. This can sometimes read quite dryly but is impressive in its organisation. Relief comes in the form of new voices and the story warms with anecdotes and vignettes from interviews, such as that with Barry Douglas, Alan Tongue of BBC Northern Ireland, board member Harold Wilkin and Sir James Galway.

The take-away? During the Ulster Orchestra’s first 32 years from 1966 to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 there were, according to the book, 3,289 deaths, 36,669 shootings, 10,142 explosions and 20,568 armed robberies. Death and violence were all around but the orchestra played on despite very low audience numbers at times. Resilience like this has to be an example for struggling orchestras everywhere. At the time of writing, we are in the middle of the Covid-19 global public health emergency, and there is considerable economic uncertainty and devastating consequences for the arts. We can take much to heart from the spirit of the Ulster Orchestra, which we can only hope will continue to flourish, as it is indeed an unfinished symphony.

To purchase Unfinished Symphony: The Story of the Ulster Orchestra, please email info [at] ulsterorchestra.com.

Published on 8 July 2020