Splendid Isolation

The piano has been around a long time in traditional music, but more usually in the public and more formal domains of dance and concert performances, and of course generally as an accompaniment to other instruments (backer or driver depending on personality and empathy). This recent CD by Caoimhín Vallely adds to the growing body of solo piano recordings in the tradition, and on the one hand offers a window into a more private, domestic form of traditional piano playing, as all the music was recorded in Vallely’s own home.

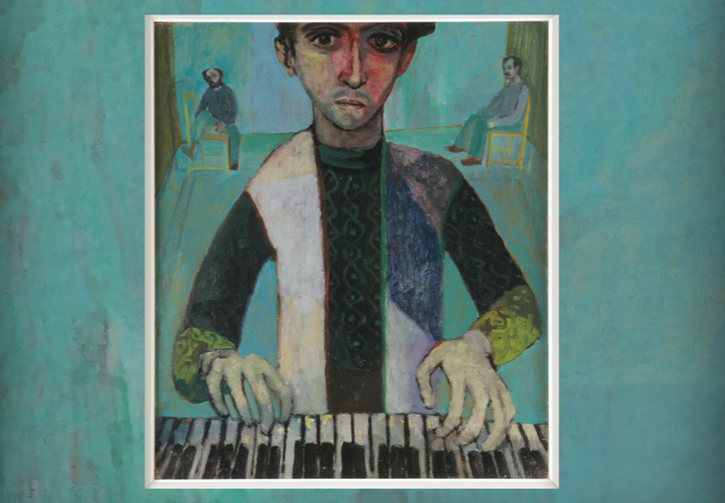

The framing of the Gerard Dillon painting on the album’s cover seems to deliberately draw your eye inwards, not just on the piano player, but on the two distant figures in the same room, disconnected in a type of splendid isolation in contemplation of the music. The style of presentation seems also designed to represent the sole pianist rhapsodising and improvising through tunes on a whim, creating music for his own pleasure.

There are nine tracks on the album, totalling over 1 hour and 21 minutes, but Vallely states in the notes that the album was conceived as continuous, and no doubt was intended to be listened to in this way too. In the days of ‘shuffle’, the fragmentation of the album, and the download, there’s a combination of the heroic and subversive about this.

Five of the tracks are lengthy, grouping together diverse airs and dance tunes. Thus the opening track preludes the Brendan McGlinchey composition ‘Splendid Isolation’ with a song, ‘The Bard of Armagh’, before surrounding the reel with the type of bodhrán (played by Brian Morrissey) and piano figurations and riffs that Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin and Mel Mercier trailblazed in the 1990s (and which crop up in a different form later on the ‘Rollicking Boys Around Tandragee’).

These fuller chordal textures and occasionally syncopated rhythms contrast with the low sonorous bassline that accompanies the tune itself. Subdued chords and fragments of the reel lead into a first halting, then a slow version of the jig ‘The Frieze Britches’, with occasional extra beats and bars disrupting the usual phrase structure.

Another interlude transforms the mood by introducing the much brighter hornpipe, ‘The Blackbird’, to finish the set. The left-hand backing here twice emerges from the tune to assume a greater prominence and to both finish the set and lead into the following song, one of three on the album contributed by Fiona Kelleher and Karan Casey.

Possibilities

The opening of the third track, the jig ‘Brian O’Lynn’, creates a very contemporary sound, even if the playing of the tune sounds like a pianist trying to remember the gist of the tune, and then getting caught up in exploring the possibilities of the accompanimental figures which emerge out of this remembrance. There’s also an exploration of the range of the piano throughout, particularly effectively on ‘Richard Dwyer’s’, where the tune begins in the bass with the chords above, then into octaves, and ascending into the upper register with a more involved harmonic line below.

Outside of the more rhythmically free interpretations of tunes like ‘The Blackbird’, there is also more straightforward tune playing on reels like ‘The Boys of Ballisodare’ and the group of tunes concluding ‘Amhrán Na Leabhar’.

The concept here of the CD as a continuous unfolding of music, almost as a stream-of-consciousness, succeeds in conveying a sense of the internal, of the inner world of the musician: it has some of the qualities of a ‘home recording’, albeit with some of the roughness and the edges smoothed out. At the same time, Vallely avoids any sense of the performance lapsing into idle noodling: there’s always a direction, a purpose, and character to the sections linking the tunes. In summary, it’s a novel and intriguing experiment in presentation, which is optimally experienced as a whole, but is also effective if listened to in smaller portions.

For more, visit www.caoimhinvallely.ie

Published on 15 May 2017

Adrian Scahill is a lecturer in traditional music at Maynooth University.