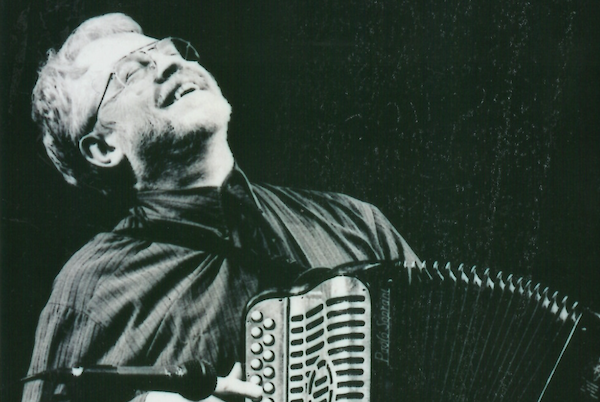

Tony MacMahon

RIP Tony MacMahon

The great Irish traditional musician Tony MacMahon has passed away.

He had been in declining health in recent years and died at St James’ Hospital in Dublin on Friday 8 October, aged 82.

MacMahon’s passing will be widely felt in traditional music circles. As a musician, a broadcaster, and as an intellect, he was highly influential. His playing, broadcasting and thinking on music inspired successive generations.

Born in County Clare in 1939, MacMahon came under the musical influence of Joe Cooley as a teenager when the Galway accordionist worked as a labourer in Ennis, ‘raising a storm of music through Clare for a few short years’, as MacMahon later wrote. MacMahon moved to Dublin at aged 18 to train as a schoolteacher, where he was further influenced by musicians such as accordionist Sonny Brogan and fiddle-player John Kelly, who he described as his ‘first mentor, a father to me and a friend, the man who taught me how to listen to music.’ In 1963, MacMahon took a year off to teach in Canada and subsequently hitch-hiked to the United States, eventually reaching New York where he shared an apartment with uilleann piper Séamus Ennis. Ennis schooled the young musician in the playing of slow airs and MacMahon described it as ‘the most enriching month of my life’. He later wrote:

I sat at his feet and he instructed me in the playing of ‘Sliabh na mBan’, ‘Bean Dubh an Ghleanna’ and ‘The Wounded Huzzar’. He was a strict master, quick to ask why you had added a particular note of embellishment where none was needed. In the playing of slow airs, he insisted on my learning the words of the song, and would get me to repeat each line after him, telling me which note he wanted me to emphasise by what he called ‘the shiver’, a gentle tremor of the accordion-bellows…

Recordings and broadcasting

MacMahon developed a unique way of performing slow airs on the accordion, with a subtle use of the basses and dynamics, and gained renown for his interpretations. He appeared on the 1968 album Paddy in the Smoke, and, in 1972, released his debut solo album (on the Gael Linn label) that still holds considerable influence today.

He was a freelance television presenter for RTÉ from 1969 and joined the station as a radio producer in 1974. This put him in a unique position in Irish traditional music and he held strong views on the role of the media in the art form. ‘[W]e have to think about the opinion-makers in traditional music, those who bring this music to the public, and how they make their judgements,’ he would later say. He was a passionate and articulate advocate of the solo performer, and, in his broadcasting work up to 1998, through television programmes such as The Pure Drop, Take Down the Lamp and The Blackbird and the Bell, he brought a range of skilled artists to public prominence. At the same time, he also played a part in the founding of the Bothy Band in 1974 (then known as Seachtar), and presented and performed in a travelling television series with Barney McKenna of the Dubliners called The Green Linnet in 1978.

In the 1980s and 90s, MacMahon’s musical partnership with concertina-player Noel Hill produced the recordings I gCnoc na Graí and Aislingí Ceoil (also featuring Iarla Ó Lionáird), which have become classics of the genre, and he was the soloist in an orchestral work by Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin, Ah, Sweet Dancer, on the Oileán/Island album.

In 1994, he devised what was to become the longest-running television series on Irish music of any kind, the archive series Come West Along the Road, which ran for two decades and was presented by Nicholas Carolan. The following year MacMahon caused controversy by speaking out on the Late Late Show against a new BBC/RTÉ series of television programmes on traditional music called A River of Sound (presented by Ó Súilleabháin), saying that ‘innovation is taking over, steamrolling tradition… Irish traditional music is being lost’. His comments sparked a national debate around the music and he later commented, ‘…it seemed to me that the body of Irish traditional performers had an almighty, long-established pain somewhere in their shared spiritual gut and it seems as if the few words I said that night stuck a finger into the wound and out came anger and frustration.’

At the Crossroads Conference in Dublin in 1996, as a keynote speaker, he articulated the basis of his thinking on music:

I think there is one basic question that music be asked – what is music for, what is its value, what can it do for us? Is it an aural carpet, a sort of ear chocolate to soothe our nerves in pubs, traffic jams or shopping centres? Or, is it a gift to humanity of such proportions that words can do little justice to it? …

It seems to me that for those who have ears to hear, this music of ours possesses the power of magic: it can put us in touch with ourselves in ways no other Irish art form can do. It can touch the pulse of ancestral memory, allowing us to redefine our dreams of what it is to be Irish. It can bring the lonely famine landscape to life, it can soothe the trauma and trouble of existence, it is possessed of the veiled eroticism of tenderness. It can adorn a moment of joy, it can sharpen a moment of sorrow. It is a gift of nature dispensed with the abandon of wild flowers.

Later years

Following his retirement from RTÉ, he returned to performing more regularly and released the retrospective recording MacMahon from Clare. He was also the subject of a radio documentary by Peter Woods, Port na bPúcaí – The Music of Ghosts. At the same time, he developed a traditional music and song stage show called The Well, followed by a poetry and traditional music show, The Frost is all Over, with writer Dermot Bolger and piper David Power. In 2004, he was awarded the Gradam Saoil (lifetime achievement award) from TG4.

A live recording with Steve Cooney from 2005 was followed by an album of slow airs, Farewell to Music, which was organised by Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh. Both were released on Raelach Records. In 2016, a tribute concert took place at Dublin City Hall and RTÉ broadcast a documentary by director Cathal Ó Cuaig, Slán leis an gCeol/Farewell to Music, in 2019. The same year, the Willie Clancy Summer School organised a tribute to the musician.

In a video interview shown during that event, MacMahon imparted his advice to young musicians:

I think my own music was directly connected with my love for the Irish language and my advice to the wonderful young players who are up and coming today is to listen out for the love we all have in our arteries… for the Irish language, and to let that influence our music.

Commenting on the musician’s passing, President Michael D. Higgins said:

It is with great sadness that the music community will have heard of the passing of Tony McMahon, one of Ireland’s iconic presences among musicians. Tony brought to performance in so many forms, places and venues the talent of a maestro. To hear him play ‘Port na bPúcaí’, for example, was to feel transported into another world. His commitment to traditional music and to the friendship of his fellow musicians was full of integrity. On behalf of Sabina and myself, agus mar Uachtarán na hÉireann on behalf of the people of Ireland, may I send my deepest condolences to Tony’s family and friends, and to the wider music community at home and abroad.

Tony MacMahon is survived by his sons Anan and Oisín and grandchildren, his wife Dr Kantha Naidoo, his brother Dermot and extended family.

Due to current government advice regarding public gatherings, a private remembrance service, limited in numbers, will be held on Sunday 17 October 2021 at 1.30pm in the Unitarian Church, St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2. The service will be available to view here: www.dublinunitarianchurch.org/webcam/.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.