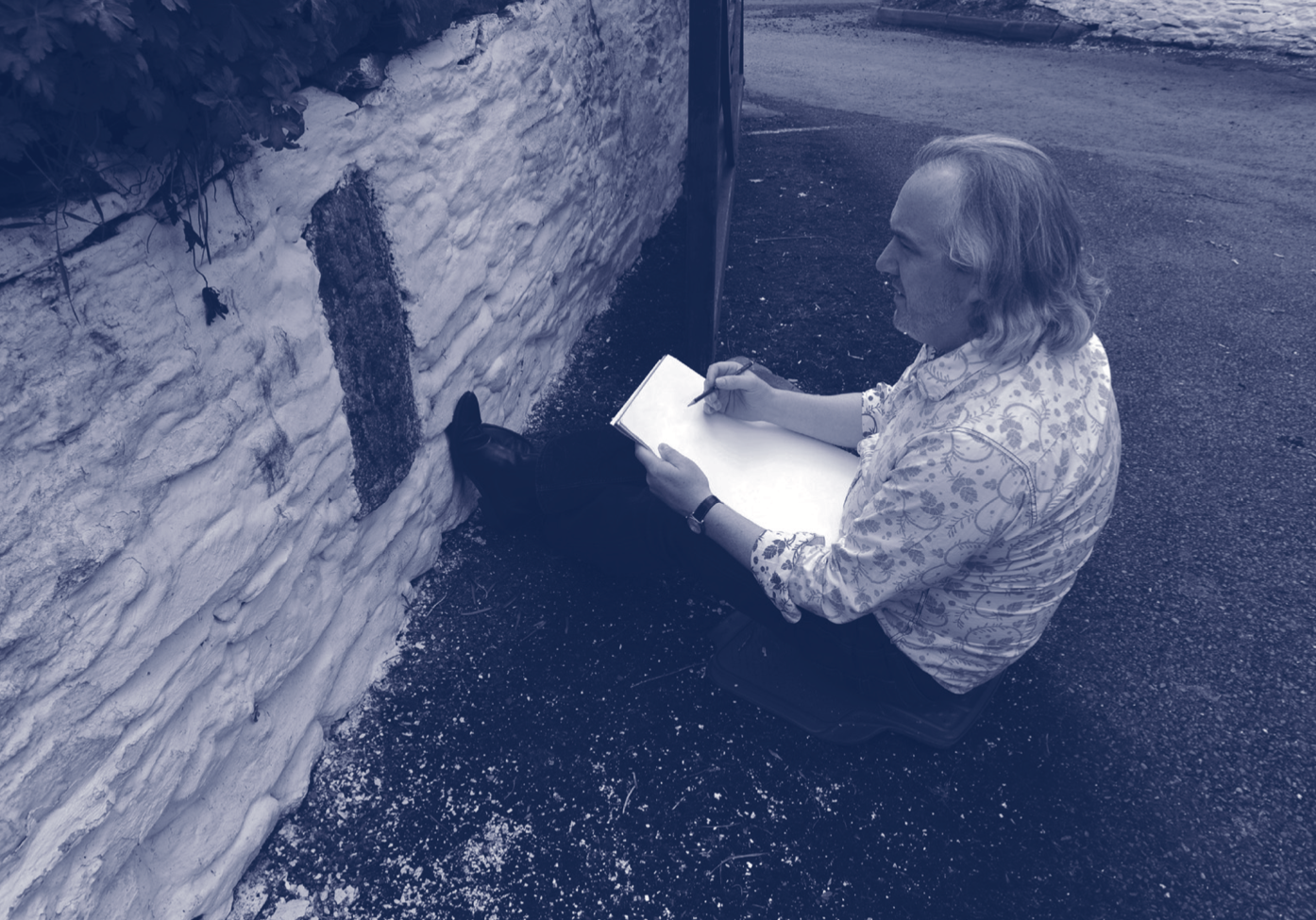

Composer Benjamin Dwyer sketching a Sheela-na-gig at Ardcath, County Meath. (Image from the booklet for 'SacrumProfanum')

Representing Ireland's Damaged Past

I do not know whether Benjamin Dwyer’s SacrumProfanum (Farpoint Recordings, 2022) is an album with an extensive set of liner notes, or a research project with an accompanying illustrative album: the booklet half of this project mostly comprises a research article of several thousand words and seventy-six footnotes. Having listened and read, I’ve come to think that the two elements are co-equal: they each work independently, but they also mutually inform and enrich one another.

The essay of the liner notes is mostly an extended academic discussion of Sheela-na-gigs, along with some more personal comments on how these figures informed, in a general way, the music of SacrumProfanum, of which they are the core focus. There is surprisingly little space given to the specifics of the music, but in giving a big-picture account of this very intellectual composer’s approach it is well worth dwelling upon.

Sheela-na-gigs are a tradition of medieval figures. In Dwyer’s words, they ‘are stone-carved representations of female figures portraying notably enlarged vulvas and (occasionally) oversized heads. Contrastingly, the rest of the body is often withered, emaciated or even skeletal, exhibiting flaccid, diminutive or missing breasts’ (p. 5). They are puzzling artefacts: they are mostly, but not exclusively, found in Ireland, and their purpose and origin is a matter of substantial academic disagreement. Of particular interest to Dwyer is ‘the range of attitudes they reveal – from defiant and aggressive to humorous and whimsical (especially when dancing). Their emphatic stare is nearly always direct and intense’ (ibid.). Dwyer is fascinated by this stare because he sees in it our conscience, clarified and intensified through the experience and example of the subaltern:

Nearly all Sheelas stare defiantly and austerely back at those looking at them. That insolent, unflinching stare is often reinforced by either a scowling grimace or a wry smirk (sometimes it is deeply ambivalent). In my view, this is one of the really powerful aspects of the Sheela – her wonderful insolence, her ‘what-are-you-looking-at’ impudence; the agency she manifests in returning the gaze upon her with an audacious ‘fuck off.’ (p. 30)

In passages such as these, Dwyer shows himself capable of remarkably eloquent oration with great moral force. The essay also gets deep into academic weeds, though: a substantial part of it is taken up with a rebuttal of the two canonical texts on Sheela-na-gigs (Jørgen Andersen’s The Witch on the Wall (1977) and Anthony Weir and James Jerman’s Images of Lust (1986)). I am not sure why anyone other than a researcher of Sheela-na-gigs would need to read this, and Dwyer’s writing style can be ill-tempered in a way I find neither dialectically helpful nor rhetorically effective, but the discussion is interesting and on all key points (with the caveat that this is not my research area) persuasive.

Dwyer supplants the account of Sheela-na-gigs offered by Andersen and Weir and Jerman with one more informed by feminist theory, in particular Barbara Freitag’s Sheela-na-gigs: Unravelling the Enigma (2004) and Therese C. Oakley’s Lifting the Veil (2009). The most important element of this understanding to SacrumProfanum is probably how Sheela-na-gigs give voice to the ‘damaged’ ‘other’. The ‘other’ here refers to women, to the Irish as colonial subjects, and by extension to subalterns in general. The ‘male gaze’ is defiantly returned, revealing what is seen as merely an ‘object’ to be in fact also a ‘subject’: that is, something capable of moral judgement, something which can hold accountable he who thinks himself above the reach of those whom he oppresses. The idea seems to be that the Sheela-na-gig returns this gaze on behalf of women through ‘audaciously exteriorizing her secret and abject interiors’ (p. 38), i.e. her vulva; she returns it on behalf of the oppressed Irish by her emaciated, Famine-starved figure; and she returns it on behalf of the long history of Ireland, which is in constant danger of being forgotten or smoothed out in response to the strictures of global capitalism, by being so often carved by amateurs, by pre-existing Ireland’s colonisation, by being crafted according to standards other than Western art’s, and (perhaps most importantly) by being such a feeble and uncertain link back to Ireland’s early history.

In all this, the Sheela-na-gig is crucially a damaged figure, and it is precisely through this damagedness that she can lash our conscience. This idea – Dwyer calls it an ‘aesthetics of damage’ – is ‘a core and essential component of SacrumProfanum’ (inside cover).

An aesthetics of damage

It is only in the music that this aesthetic can be fully articulated, and indeed the album opens with Siobhán Armstrong playing a minor-mode tune on late-medieval Irish harp. The melody is beautiful (it turns out to be ‘Bí Íosa im Chroíse’ in retrograde, the Sheela’s leitmotif), but the tuning is uncomfortable and it sounds to our modern ears ‘damaged’ – together, they create a subtly powerful opening.

What they open is an eleven-part hour-long work for amplified ensemble and tape. The musicians are Armstrong (late-medieval Irish harp, sean-nós singing, narration), Garth Knox (viola), Emma Coulthard (flutes and piccolo), Donnacha Dwyer (taped uilleann pipes), and Benjamin Dwyer himself (bowed guitar and taped harp). Dwyer composed the music; the texts are from collections of old Irish poetry apart from ‘Sheela-na-gig’, which was written by Jona Xhepa.

The aesthetics of damage recurs throughout the album, from Knox’s viola’s scratch tone on ‘Chloran’, to the bitter texts, to the unnaturally, uncannily heightened keening of Donnacha Dwyer’s uilleann pipes in ‘Expugnatio’ and ‘Cooliaghmore’. The damagedness perhaps reaches its roughest with ‘HAG’, in which Armstrong’s narration degrades from Xhepa’s poetry of the previous track, ‘Sheela-na-gig’, to guttural sounds and barked-out expletives – ‘cunt!’, ‘whore!’ All the while, Coulthard’s flute and Dwyer’s guitar rasp and gurgle in frustration and rage.

But the damagedness is often more subtle. The final track, ‘Caoineadh’, is a beautiful sean-nós rendition of a text that was spat out earlier in the album, on ‘Cailleach’. It is only through reflection on the text and its context in the album that you come to see it as not just sad, but as hopelessly sad: about the irrevocable loss of friends’ deaths, and the permanent scars they leave on the living.

All the performances are fantastic. For instance, Armstrong’s recitation of Xhepa’s ‘Sheela-na-gig’ drips proud disdain, as does the hissing choir of flute and bowed guitar that flanks her. Or again, Knox gives ‘Chloran’ and ‘Rutland’ an intoxicating heavy, dark drive. Goodness knows how you could notate such things – as Dwyer himself says in the liner notes, this could only have been a collaborative project.

The bitter anger that suffuses both text and music of SacrumProfanum makes for a less bleak work than you might think. It reminds me of the African American writer James Baldwin, who wrote fiery diatribes against US racism, but who nevertheless gained enormous popularity in the 1960s even among the white people who were his primary targets. The reason, I think, is that purely by Baldwin’s commitment to getting his message across, he expressed a faith in white Americans that they could, with work, overcome their racism. Similarly, SacrumProfanum, though a morally challenging work, in a deep way constantly reaches out to the listener. This is due not only to the compositional choices, which balance quiet introversion and fire, but also to the energy and commitment of the performers, which allow the full, wide breadth of the work to shine through. In this, it expresses, like Baldwin’s essays, a faith toward the listener that is encouraging, even flattering. And so at the end of the day, SacrumProfanum is not just surprisingly non-bleak, but positively enthralling.

To purchase SacrumProfanum by Benjamin Dwyer, visit www.farpointrecordings.com/product-page/benjamin-dwyer-sacrumprofanum.

Click on the image below to listen.

Published on 25 May 2022

James Camien McGuiggan studied music in Maynooth University and has a PhD in the philosophy of art from the University of Southampton. He is currently an independent scholar.