Publishing Britain

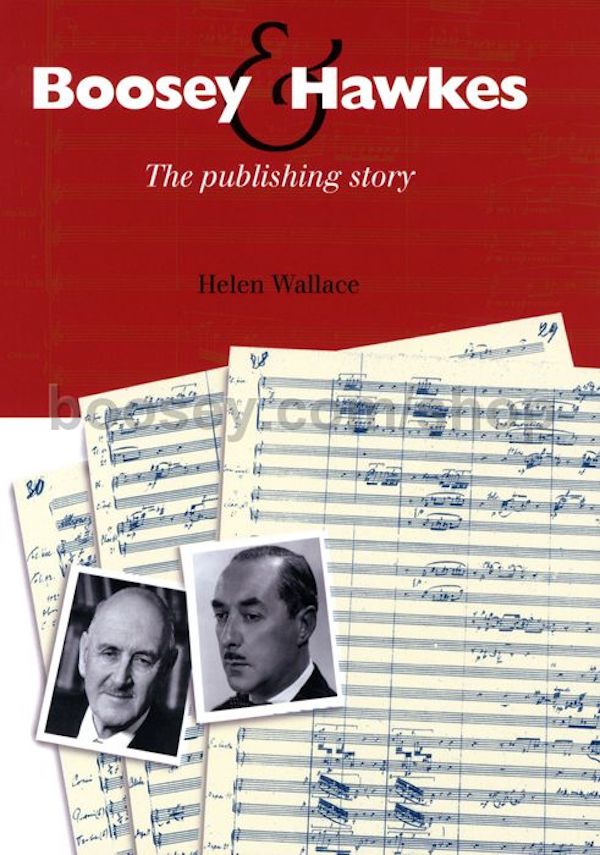

Helen Wallace, Boosey & Hawkes: The Publishing Story,

Boosey & Hawkes, London, 2007, 256pp

Helen Wallace tells us that this book was not undertaken as a vanity project. Its aim from the outset, she says, was to give an impartial account of the triumphs, trials and tribulations of one of the great music publishing houses, and the result is a lively and eminently readable record of eighty years of activity. The well-known Boosey & Hawkes premises at 295 Regent Street in London, which the firm had occupied for 75 years, was being vacated in 2005 and Wallace, who was commissioned to produce a brief summary of the company’s history, had a mere four months to examine the entire archive. As she sifted through thousands upon thousands of files, the projected word length of 20,000 words grew to 150,000. Even so, much material of considerable interest had perforce to be omitted. But although understandably incomplete, the story as recounted here is an absorbing one, rich in colourful personalities and generously spiced with intrigue.

Boosey & Hawkes was formed in 1930 when two existing music publishers decided to come together and combine resources rather than remain competitors. Boosey & Sons, the older of the two firms, was established in the late eighteenth century as a London lending library. The founder’s grandson subsequently expanded the musical side of the business, and his son, John Boosey, first began to publish music by issuing cheap editions of the classics for parlour consumption. In 1867 Boosey & Sons launched the celebrated London Ballad Concerts to promote the sale of their sheet music. These popular events, which continued until 1933, proved the most successful formula on the market, combining an irresistible mix of star singers, sentimental ballads, orchestral lollipops, and exotic virtuosi. The firm moved to 295 Regent Street in 1874, where John Boosey was assisted by his nephews and where his great-nephew Leslie took over in 1920.

Geoffrey and Ralph Hawkes inherited Hawkes & Son from their father also in 1920. This too was an old family business that dated back to 1865. Catering to the large market provided by the British Empire, it specialised in the manufacture of brass and reed instruments and in the publication of repertory material for brass and reed bands. The remainder of its publishing catalogue was frankly geared to current popular taste and included many orchestral arrangements and a wide range of instrumental tutors. The two brothers divided the business between them: Geoffrey managed the instruments side, and Ralph the publishing.

In sketching the background to the merger of the two firms, Wallace offers an interesting summary of the difficult situation in which music publishers found themselves in the 1920s. Up to this time profits were derived principally from the sale of sheet music. A popular item could sell thousands of copies, a very popular one up to a million. But circumstances were changing. The advent of talking cinema and the replacement of live music by mechanically reproduced sound not only meant unemployment for the musicians who played in the many cinema orchestras, but also a correspondingly dramatic drop in sheet music sales. Radio had a similarly adverse effect. By 1926 two million British homes already enjoyed the dance bands broadcast by the BBC, and this new and effortless access to music led to a drastic decline in amateur music making. Music publishers had by and large been opposed to the Performing Right Society when it was formed in 1914, believing that an additional charge for performing music would merely deter people from buying it. But people were simply not buying music any longer. Leslie Boosey recognised that performing rights were now the crucial issue both for publishers and composers alike, and he had the foresight to join the board of the PRS against the prevailing opinion. He took an active part in a number of ensuing legal battles, and in 1929 he helped to secure the defeat in the House of Commons of the infamous ‘Tuppence Bill’, which, if passed, would have meant that two pennies, a nominal sum, is all that would have been legally payable for the performance of any piece of music, whatever it was.

It was on the board of the PRS that Ralph Hawkes and Leslie Boosey had the opportunity to assess each other’s strengths, and their combined talents proved dynamic. Wallace provides telling thumbnail sketches of the two men: Boosey, a man of quiet but determined confidence; and Hawkes, a charismatic personality, with a vital and active mind and an extraordinary flair for music publishing. Despite the predominantly popular repertoire both firms had hitherto published, at the initial board meeting of Boosey & Hawkes a decision was made to develop the serious music catalogue. To a great extent, this decision determined the future course of the firm. At first it meant building on Boosey’s current list of works by Elgar, Delius and a few other established English figures. It was not long, however, before a new policy of expansion was introduced, and by 1933 Ralph Hawkes, who had already acquired the British agency for Universal Edition, had embarked on a mission to find new composers in earnest.

Britten’s Involvement

By 1934 Hawkes was becoming more and more intrigued by the music of the young Benjamin Britten. A few of Britten’s works had already been brought out by Oxford University Press, but, impatient of their dithering over the publication of A Boy was Born, he was easily persuaded to throw in his lot with Boosey & Hawkes. It is surprising to learn that the firm actually made a loss on Britten until 1946 when Peter Grimes was produced, and that Hawkes frequently found himself having to justify to the board of directors why the firm continued to publish and promote him. Britten immediately took an active interest in the running of the company, a quality that marks him out from almost all other major composers, and, as he acquired a considerable degree of influence, he figures prominently in the pages of Wallace’s history. As early as 1936 he was urging Hawkes to sign up Aaron Copland, which he duly did in 1938. In the same year, having made a personal visit to Hungary for the purpose, Hawkes persuaded Bartók and Kodaly to publish with the firm. But he did not always succeed in getting what he wanted, nor was he always infallible in his judgments. One interesting thread running through the narrative at this juncture is his failure to attract Walton, who remained with Oxford University Press, possibly, as Wallace suggests, to separate himself from wunderkind Britten. Tippet was rejected in 1938 after he submitted his school operetta Robin Hood, and by the time his star was in the ascendant he had already signed up with Schott.

Undoubtedly one of the most important deals Hawkes brought off was the purchase in 1943 of the copyrights of German firm Fürstner. These included Richard Strauss’s operas, which were more valuable than the all of B&H’s current orchestral works put together. The transaction put the company on a completely different footing internationally. It gave them a considerable advantage in the opera world, and Hawkes fully appreciated how Strauss’s works could be used in bargaining to secure productions of other operas in their catalogue, particularly those of Britten whose career benefited accordingly. This coup was followed by a virtually unbroken succession of successful moves. The Anglo-Soviet Press was formed in 1945. The sole purpose of this wholly-owned B&H subsidiary was to publish Soviet works in Britain in conjunction with the Soviet government’s own rights organisation, and it led to relationships with Shostakovitch, Prokofieff, Kabalevsky and Khachaturian. In 1945 Hawkes concluded a deal with Koussevitzki for the purchase of Edition Russe, which published music by Rachmaninoff, Prokofieff and Stravinsky, including The Rite of Spring and Petrushka. And in 1947 Stravinsky signed an exclusive contract for the publication of new works.

In the course of her narrative, Wallace touches on the histories of the other branches of the firm around the world, paying particular attention to the story of the highly successful American branch whose development was of such importance to Ralph Hawkes, and whose activities are fascinatingly counterpointed with those of the parent company in London.

Ralph Hawkes died of a heart attack in 1950. His loss was keenly felt, not only because his exceptionally acute business acumen seemed irreplaceable, but also because his death created a vacuum that was filled by power politics. Ernest Roth now moved to the center of the stage. He had joined the firm in the late 1930s as a refugee from Nazi Europe, and became one of the most powerful men in the firm, first as Managing Director and subsequently as Deputy Chairman. He comes across as a chilling figure in Wallace’s account. Unquestionably charming and brilliant, he was also evidently ruthless, and – although this often remains tantalisingly unclear – someone who appears to have been at the centre of a great deal of the internal intrigue.

Britten distrusted Roth, who in turn seems to have regarded the Englishman as a talented local composer in contrast to Stravinsky, whose genius he revered. A sympathetic personal contact in the firm was necessary for Britten, who expected more from his publisher than an interest in his music merely as a salable commodity. In the 1950s this contact was a man called Anthony Gishford, who, Wallace suggests, found himself obliged to resign in 1958 because of Roth’s machinations. Britten reacted strongly to Gishford’s departure, and made it clear that he was not happy. He also had reservations about the way B&H were handling matters generally, believing that the instrument manufacturing interest was compromising the publishing interest. He proposed that the firm be reorganised with two separate boards of directors, one for each division. Although this did not happen immediately, the ongoing poor performance of the instrument manufacturing side of the business under Geoffrey Hawkes, and the resultant difficulties in which the firm found itself by 1960, meant that a reorganisation was eventually undertaken along these lines. Geoffrey Hawkes died in 1961 and three years later Leslie Boosey retired. But while Boosey’s son Simon worked for the firm, there was never again either a Boosey or a Hawkes on the board of directors.

Although Britten was temporarily appeased, he remained dissatisfied with the stagnation of the publishing catalogue and the fact that so few vital new composers had been taken on in recent years. At his suggestion, Donald Mitchell was recruited to address this unsatisfactory situation and he was responsible for signing Peter Maxwell Davies and Nicholas Maw at this time. Roth, however, resented Britten’s influence in the firm and found a reason to dismiss Mitchell. It was the final straw as far as Britten was concerned. This time there was no communication from Aldeburgh: Britten simply did not sign his new contract. In February 1964 he wrote to Mitchell from Venice, where he was composing Curlew River, to commiserate with him: ‘Don’t worry … I’m sure there will be some future. I occasionally dream of Faber & Faber – music publishers!’ Mitchell, who was then in charge of the music-book list at Faber, took the hint and went straight to the top with the idea. T. S. Eliot responded positively and by May of that year a new music publishing company, which had literally been dreamt up by Britten, was established.

Reputations

One of the most interesting strands running through the later sections of the book is the impact on music publishing of the divide that had opened up in the 1960s between the cloistered and highly subsidised world of contemporary music and the more commercial sector where programming was based on ticket sales. It did not seem likely that anything the post-war avant-garde might do would yield the kind of revenue that the music of Stravinsky, Prokofieff or Britten yielded. David Drew was appointed to the staff of B&H to steer a course through the ideologies that bedevilled contemporary music and to try to discover vital new talent. He stated the firm’s position soberly and bluntly:

Mastery of a ‘central, dominant or leading style’ is acquired with such speed and efficiency by today’s more gifted and well-placed composition students that the very concept of mastery has lost its post-Beethoven connotations… a catalogue of more-or-less impeccably qualified and intelligent young composers could be assembled overnight with built-in guarantees of commissions, first performances and laudatory press. … But the fact remains that the enduring quality of a composition is in the last resort determined solely by the quality of its composer; his or her relationship to any ‘central, dominant or leading style’ is essentially an academic question, and one to which the public … will remain supremely indifferent.

But Drew was not only concerned with finding new talent. He was also interested in promoting the work of gifted but neglected figures, and as a result of his policies the music of Gerald Finzi, Igor Markevitch, and Roberto Gerhard, for example, began to receive the kind of exposure it merited. One of the most remarkable stories told in this book is the rehabilitation of the reputation of Berthold Goldschmidt, who was eighty years of age when he came to Drew’s attention in 1983. Goldschmidt’s career in Germany had ended abruptly after the Nazis came to power, and in England after the war the British music establishment had consistently rejected his essentially tonal music. He had been almost completely ignored from the 1930s until David Drew and B&H gave him a new lease of life. Not only were his earlier works now performed to great acclaim but he also began to compose again after twenty-five years of silence.

In 1996 there was a major crisis in the company when the principal American shareholder decided put its controlling stake on the market. The music publishing division now faced being taken over by a multinational corporation – Warner, Sony, Polygram, and EMI were apparently interested – and the company had the uncomfortable experience of seeing the major publishers of pop music coming in to examine the books. A full-scale campaign to ‘save’ B&H from being swallowed up into a faceless media organisation was spearheaded by Donald Mitchell, now chairman of the Britten estate. A letter to The Times, signed by Mitchell, Harrison Birtwhistle, James MacMillan, Oleg Prokofieff, John Stravinsky, and representatives of the Holst and Elgar estates and the Delius Trust, declared that such a takeover would ‘cause irremediable damage to the British musical heritage’.

By May 1998 the crisis was resolved when B&H managed to raise a staggering £33m to buy out the controlling interest. Almost immediately after this narrow escape, however, the survival of B&H was once again in question when large-scale fraud was discovered in the US instrument distributing company in Libertyville, Chicago. The only solution was for the company to divest itself of the instrument business altogether. This was accomplished by 2003, and the path was now clear for the publishing division to become a private company once again. The following year, 2004, it was announced that B&H would enter into what Wallace describes as a strategic partnership with Schott, each company providing services to the other: B&H would provide royalty, accounting and copyright control services, and Schott would be responsible for distributing, selling and marketing. The famous hire library was moved to Schott’s new warehouse in Mainz, and in 2005 the old Regent Street premises were finally vacated.

The Irish composer’s reaction to this book is likely to be wistful envy as he reads of the extent to which a dynamic and resourceful publisher can shape a compositional career. It becomes obvious that the inability of the work of most Irish composers to make a mark internationally has largely been due to the absence of the high-powered and effective promotion a firm like B&H can provide. Without it, no music, however great, can make real headway; and with it much music that is less than great can achieve a considerable, and sometimes undeserved reputation. Wallace tells an interesting story that illustrates this point dramatically. When, in 1985, the publishing firm of Belwin Mills (formally connected with B&H in the 1930s) was bought by Columbia Pictures, part of the Coco-Cola Corporation, Carlisle Floyd, the composer of the popular opera Of Mice and Men, saw his work disappear from the stage. In the vast empire of a multinational conglomerate Floyd and his work clearly counted for little or nothing. But he eventually wrested his copyrights from Belwin and took them to B&H in 1990. Over the next fifteen years the opera received more than 100 performances.

Published on 1 November 2007

Séamas de Barra is a composer and Senior Lecturer at the Cork School of Music.