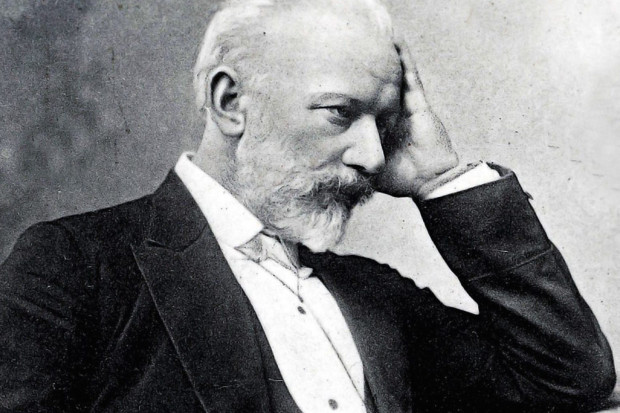

Currach-burning in Nick Roth’s ‘Crann’ (Photograph: Esme Pum McNamee)

Our Predicament in Sharp Focus

Given the seriousness of the climate crisis, it is not surprising that themes related to nature have become prominent material for artists. Crann, by Nick Roth, is a setting of Richard Berengarten’s poem Tree for three female voices featuring singers Michelle O’Rourke, Caitríona O’Leary and Olesya Zdorovetska. Commissioned by the IMRAM Féile Litríochta Gaeilge (Irish-language literature festival), the piece uses an Irish translation of the poem by Gabriel Rosenstock and includes a film directed by Laura Hilliard that shows the three singers performing the piece intertwined with various symbolic scenes.

Berengarten’s Tree (1978–79) is a 365-line chant poem that celebrates the power of trees as givers of life and as sources of constant renewal and protection. The poem also traces the presence of trees through history, from their symbolic function in ancient mythology and literature to acting as outposts of nature in modern urban landscapes. In its rhythmic chant structure, it draws on ritualistic practices, and, as one reads the poem, the lines seem to flow with a meditative quality that ultimately points to a higher state of being where nature and human consciousness are in harmony with one another.

The first thing one is immediately drawn to with Crann is how much this ritualistic aspect is brought to the fore. In Hilliard’s film, the three female singers, dressed in black, resemble ancient shamans invoking nature spirits in some kind of pagan ceremony. At various points, the film inserts scenes including the making and setting alight of a currach as a symbolic offering to the sea. In the same vein, Roth’s setting is punctuated by a recurring refrain – slightly varied each time – in which all three voices begin in unison recalling the antiphon psalmody of medieval chant.

Musically, the piece draws on a range of different styles with echoes of Gregorian plainchant, Pérotin, Gesualdo and folk song all interwoven within a thoroughly contemporary musical language. The idea here seems to be to touch on various historical and geographical styles mirroring the way in which Berengarten’s poem locates the tree as a constant image in myth and literature separated by great expanses of space and time.

Natural touches

Although dissonances are frequent, the more one gets absorbed in the piece, the more it begins to feel as if one is not listening to a contemporary work at all but rather an act of pagan worship. Particularly interesting is the way the piece makes use of a variety of vocal effects and additional sounds from various objects. Near the beginning of the setting, on the words ‘crann gíoscánach / beag beann ar thoirneach’ (‘creaking tree / enduring thunder’) the texture breaks off into pitch-less growling against the breaking of bark. Shortly later, triggered by the words ‘slabhra óir’ (‘golden chain’), the singers gently begin fondling a metal chain in their hand producing a rain-like background effect. In contrast to a lot of contemporary choral music where such effects tend to stick out awkwardly, these touches seem natural, rarely amount to literal word-painting and imbue the music with an earthiness and tactility that prompt the listener to form their own associations.

There are many fascinating moments but two in particular will serve to demonstrate the sheer range of the piece. At 13:11 there is a solo section consisting of a simple melody whose movement resembles plainchant. When it returns to the tonic, the other voices enter in unison with the refrain, gently touching on semi-tonal dissonances before drifting away towards a more remote tonality. This is the piece at its most traditionally reverential. Slightly later at 17:11, however, there is a much more anarchic section of wolf-howls as the voices loop and soar resembling a primeval rite. That both of these sections seem to fit so naturally into the same piece is testament to the overarching vision behind the project and the stunning performance by the three vocalists. While Roth is a composer who frequently tries to pack the entire world into a single composition, in this case all the elements come together beautifully.

While the work does not engage with environmentalism per se, it is impossible not to read a wider meaning into the work. For me, the problem with many of the environmentally themed works which I have heard is that they tend to spell out the obvious – that we must radically alter our relationship with the planet if we are to survive – in a rather pedantic and tedious way by pedaling a mixture of scientific data and sentimentalism. Given the audience profile for contemporary music, the result is frequently a forced and artistically unsatisfying form of preaching to the choir. By drawing on ritual, Crann connects our contemporary world to a mythic past and a sense of epic time stretching back centuries where nature and people had a closer, interdependent and ultimately more harmonious relationship. In this way, it constitutes a deeper and more powerful reflection on our current predicament and throws our fractious relationship with our natural surroundings into even sharper focus.

Crann is available to view at the link below.

Published on 24 February 2021

Adrian Smith is Lecturer in Musicology at TU Dublin Conservatoire.