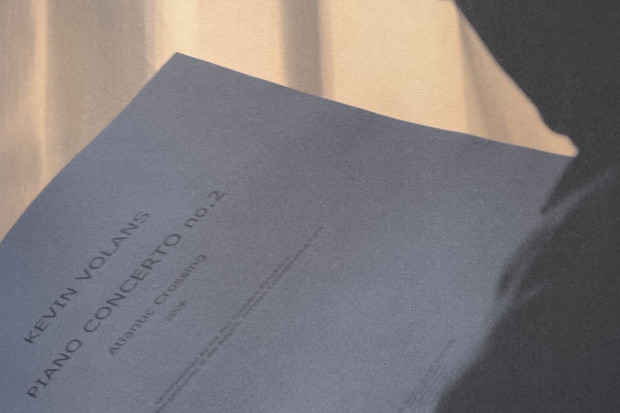

Gerald Barry and Adrian Mantu following the world premiere of 'Cello Concerto' in Galway.

Music Out of Time

Postponed in 2020 as a result of the pandemic, and again in 2021, this concert of three cello concertos represented the culmination of the first year of Cellissimo, the new triennial cello festival created by Music for Galway.

The festival is also one of the legacy projects of Galway 2020, but as the audience settled down in the hall in Leisureland (a swimming pool complex), we are reminded once again of the failure of that much-heralded year of culture and its €23.7m to make any concrete moves towards a multi-space music venue for Galway. If there was ever an example of undervaluing local knowledge and ability in favour of image and brand, then Galway 2020 was it. But Music for Galway is one of the few organisations who actually managed to produce something substantial out of the year, and it has also since taken the initiative to conduct a feasibility study into a concert hall.

On 11 May, there was a large audience to welcome the two new cello concertos by Gerald Barry and American composer Julia Wolfe, co-commissioned with the Cello Biennale Amsterdam, followed by the famous Elgar cello concerto of 1919. Four cellists performed – Naomi Berrill, Adrian Mantu, Jakob Koranyi and Laura van Der Heijden – with the RTÉ Concert Orchestra conducted by David Brophy.

The concert began with Fragments by Bill Whelan, which received an online premiere last year. The title refers to the construction of the Galway Cello, an instrument built specially for the festival, and lines by different poets that Whelan has drawn together. Performed by Berrill on cello and voice, she seemed very at home with the work, binding Whelan’s characteristic harmonies and shifting melodies and connecting strongly with the audience. It’s an attractive short work, but having heard it online and live, I feel a singular poetic voice in the lyrics would be stronger than the mixture of lines which seems to draw the work in different directions, even if that does reflect the instrument’s origins.

In Barry’s programme note for his Cello Concerto, he tells us that the music for the first movement is ‘based on my opera The Intelligence Park’. No doubt about that. The first movement is heavily based on the ‘Banquet of Dummies’ interlude from that 1980s work, extended and orchestrated for larger forces. But is that what we should expect from a newly commissioned work? In the original, the chamber ensemble allows some nuance to come through, but here it seems forced. The movement consists of an angular rising motif, which Barry emphasises and intensifies, but whereas this kind of unwieldiness and toying with the orchestra and soloist comes off well in other Barry works, here it fell flat.

The transition to the second movement is a minute of wind machine. In an interview with the Irish Times before the concert, he says he couldn’t remember why he put it there (‘I wondered, why did I do that? What’s that for? I had to think back, because I hadn’t looked at it for years’), but then he says, ‘it’s a bridge, a kind of aural, psychological bridge from the first half of the music to the second half.’ It did not feel like that, more like an empty gesture. But still we hoped that the second movement would draw us in.

Movement two began with a sequence of solo and chordal statements that felt slightly connected to the first movement, and then the most engaging part of the work began: a series of chromatic runs on cello, creating a bee-like effect and played with fervency by Mantu, as if he was in pursuit of the sound itself. But the work faded away again to the earlier texture until a clever ending where it ends mid-phrase. Barry can produce works that are challenging and outrageous yet playful and deeply satisfying, such as his recent extraordinary opera Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, but we had little of that energy and adventure here.

Wolfe’s work, Wind in My Hair, opens dramatically with a minimalist pulse of repeated phrases for soloist Koranyi and strings accompanied by drum kit. The composer’s short programme note begins: ‘On the road, wind in my hair. Land rushing by…’, and the opening captures well that sense of motion with surroundings passing by in a blur. Every now and then the work pauses for long rising notes, but the pulse remains underneath. Later, the cello comes to the fore in rising and falling glissandi over sustained chords, increasing in intensity until it resolves to solo cellist again, swaying between notes and gradually building a chord before orchestra returns. The work had plenty of energy and technical brilliance from Koranyi, but I could not help feeling that this music firmly belongs to a pre-pandemic world. It leaves little space to think, and if anything the pandemic forced that upon us. The appeal of these driving rhythms was once that they reflected our technologically transforming world and the pace of our modern lives, but now they seem to almost represent the relentlessness that has marched us into ecological disaster. When the work ended with a sudden stop, one of the brass section’s phones was not on mute and it rang like an alarm, thus marring the ending, frustrating Koranyi, and seeming to indicate that indeed time was up.

The Elgar Cello Concerto written in 1919, performed by van Der Heijden, seemed to be the only work that could carry the weight of the world today. But even then, it felt like the chemistry between soloist and orchestra was slow to come until the latter two movements.

This concert had an incredibly ambitious programme, and Music for Galway should be congratulated. Its design and scale was a significant achievement and follows other notable events such as the Paper Boat community opera last month, the Stanford festival in January, the online Cellissimo festival last year, and the Goldberg festival before that. However, the interesting thing about works written just before the pandemic, yet not performed until afterwards, is that they are literally now out of time. The pandemic has shifted our understanding of our lives in ways we are still figuring out, and the music of this time is still being born.

For upcoming Music for Galway events, visit https://musicforgalway.ie.

Published on 19 May 2022

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music.