Music in 18th-Century Cork

… and the best of all ways

To lengthen our days

Is to steal a few hours from the night, my dear!

I wonder how many readers will know that the writer of those lines, a Dubliner, took music lessons from a Corkman who was the leading Irish composer of the late eighteenth century and also one of the most successful and fashionable music teachers in Dublin at the time. Come to think of it, I wonder how many will recognise the lines and know who the author was, let alone who his music teacher was? Perhaps not many.

The musical environment which produced the above composer was, according to all the evidence, rich and full of variety. Musical life in Cork City during the eighteenth century featured many visiting musicians in concerts which were an important part of life then.

Crofton Croker, writing in 1824, and looking back to the end of the eighteenth century writes: ‘Concerts and meetings of musical societies were frequent in Cork, and the recollection still survives of the excellence attained by several of the amateur as well as professional members.’[1]

Attention had already been drawn to this thriving state of music making, albeit in a delightful and amusing piece by Charles Smith, the first important historian of Cork. In a passage, subsequently justifiably described by Crofton Croker as ‘somewhat bombastic’, Smith really seems to get carried away by his subject:

Besides the public concerts, there are private ones, where the performers are gentlemen and ladies of such good skill, that one would imagine the god of music had taken a large stride from the continent, over England, to this island … and those who have no ear for music are generally so polite as to pretend to like it. A stranger is agreeably surprised to find in many houses he enters Italic airs saluting his ears; and it has been observed that Corelli is a name in more mouths than many of our Lord Lieutenants! The humane and gentle disposition of the inhabitants may, in some measure, be attributed to the refinements of this art.[2]

That Smith had filched that passage, without acknowledgement, almost verbatim from a little known publication, perhaps adds zest to our enjoyment of it, for it had appeared originally applied to the whole island, eleven years before Smith’s book was published.[3] Nevertheless, no matter how ‘bombastic’ we may think the description, the fact is that Smith, although cheating a bit, was describing a musical environment of great vitality.

After the Concert there will be a BALL

This vitality was reflected in the columns and advertisements of the Hibernian Chronicle, which was the newspaper in Cork during the second half of the eighteenth century. It is a mine of fascinating information about many aspects of Cork life at that time, not least about the music. An examination of the concert advertisements is revealing of a number of things: the range of music included in each concert, often the sheer quantity of music involved, the late starting time often advertised and finally, an almost universal announcement to the effect that: ‘After the Concert there will be a BALL’.

Often the concerts would begin at 9 p.m., and even with an earlier start, proceedings must often have continued well into the small hours of the morning. This indicates a stamina on the part of our eighteenth-century forerunners not usually found in today’s music lovers. Without doubt Cork music lovers then knew how to ‘steal a few hours from the night, my dear’!

In the summer of 1788, mention of a visit to Cork by the celebrated flautist Andrew Ashe appeared in the Hibernian Chronicle:

We are happy to announce to all lovers of Music the arrival of Mr Ashe in this city, whose distinguished abilities on the Flute have been universally admitted throughout Europe, his generous offer to perform gratis for the Infirmary reflects additional credit on his musical talents, and will, we are persuaded induce a discerning public to honour his night with their friendly patronage.[4]

The following advertisement appeared in the same issue of the Chronicle:

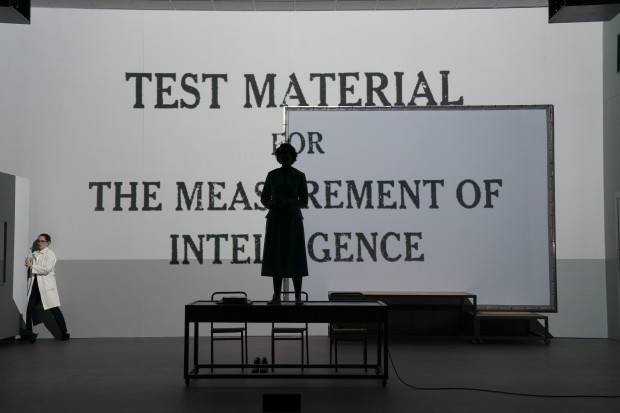

Great Room, George’s-Street [now Oliver Plunkett Street]. Mr Ashe’s Night. (By particular desire) On Thursday Evening, the 14th instant, will be a GRAND CONCERT OF MUSIC, in which Mr Ashe means to introduce several pieces of his own Composition for the Flute, also a concerto for Two Flutes, both instruments to be played by himself. The Orchestra will consist of the Music Society, and other gentlemen who have consented to give their kind support on the above occasion. [Then the inevitable:] After the Concert A BALL. The performance to begin precisely at 9 o’clock. Tickets each 4s 4d may be had at Messrs Knights, Printers, A. Edwards, Bookseller, at the Printers hereof, and of Mr. Ashe, Ann-Street, Cork. Particulars at large in the Bills.[5]

In the event this concert was postponed until the following Wednesday, allowing the full programme to be advertised in the next issue of the Hibernian Chronicle as follows:

Act I

Sinfonia – Stamitz

Quarteto, Flute – Pleyel

Song: ‘Though Bacchus may boast’ – Mr Bowden

Overture – Haydn

Act II

Double Concerto on Two Flutes – Mr Ashe

Song (by particular desire) ‘How sweet the Love’ – Mr Johnson

Concerto, Flute – Mr Ashe

Duetto ‘As I saw fair Clora’ – Bowden and Johnson

To conclude with a Full Piece

After the Concert A BALL[6]

It seems it was worth Ashe’s while to remain in Cork for a couple of months for he gave a concert just before leaving at the end of September. If one considers that Ashe was perhaps the eighteenth-century equivalent of James Galway it may help to put the visit in perspective. Indeed the parallel is quite close – Ashe was also born in the northern part of the country, in Lisburn, County Antrim, in 1758.

Churches in the City

The churches in the city, in particular St Peter’s in North Main Street, Christ Church South Main Street and St Fin Barre’s Cathedral were centres of much musical activity during the century. William Gibson of Dublin was commissioned to build an organ for St Peter’s which was inaugurated in grand style in October 1790.

On Sunday last was opened for the full Exhibition the new organ in St Peter’s Church made in this city by Mr Gibson of Dublin, when two select pieces from Handel’s Messiah were performed viz. ‘I know that My redeemer liveth’ and ‘He shall feed his flock’, which were agreeably accompanied by the vocal performance of a promising young girl (Rosetta Edgecombe) from the Foundling Hospital in our city. The organ met with universal approbation, and was done great justice by Mr Shaw, whose performance, both in the voluntary and accompanyments were excellent, particularly on the swell stop, he showed the greatest taste and expression … This organ has been erected by the indefatigable exertions of a few Gentlemen of the Parish, who obtained through their own solicitations private subscriptions and had no assistance from any Parish Rate for so costly and great an undertaking. It is entirely executed in the modern stile, and the front is perhaps the most beautiful in the Kingdom.[7]

A piece of Cork chauvinism by the correspondent of the Chronicle, possibly well justified! One wonders about the fate of that organ when the church was closed – was it in the nineteen-forties or -fifties? A few years ago Cork Corporation rescued the building from impending dereliction and it is now more or less sensitively restored and used as a ‘Vision Centre’.

In the 1750s Christ Church South Main Street acquired a new organ, the construction of which was paid for by the then Cork corporation. However, they drew the line at subsidising the salary of the organist when the authorities of the church found themselves in financial difficulties in 1761.

At St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, throughout the century, much attention was paid to the organ by the Dean and Chapter, demonstrating a concern on their part with the musical standards at the Cathedral. On 25 April 1710 the Cathedral commissioned a new organ from John-Baptiste Cuville. On the same day the Chapter, in a rather mean move, decreed: ‘That the Choir be discharged, and all the servants belonging to it from further attendance, receiving their salaries to June 24th and their means to be applied to the service of the Church’.[8]

A move occasioned no doubt due to the work of building the new organ. An additional £40 was ordered to be paid to Cuville in April 1711 for ‘The cornet stop in the organ’[9] – presumably this was in addition to the original specification. Then on 6 November 1712: ‘The articles of agreement between the Dean and Chapter and Mr John Baptista Civille[10] for keeping the organ in repair, to be signed by the Dean.’[11]

Edward Broadway had been appointed organist on 13 April 1712 so presumably the choir and choral services were restored at that time. Broadway resigned in 1720 and was replaced by William Smith who remained in office for a remarkable sixty-one years. And some of them must have been pretty traumatic, for in 1735 a decision was made to demolish the old medieval cathedral and replace it with a small rather ugly building (see photo). So the Cuville organ had to be dismantled and then reassembled in 1739:

Whereas the organ of the Cathedral which was pulled down, on which £55 5s was expended, is repaired and put up. Ordered that an application be made to the bishop for said sum out of the profits of St John of Jerusalem, for the repair of the said organ it being necessary to accompany the choir in their singing …[12]

Only a year later a further application was made to the bishop for £150: ‘For the purchase of a chair organ for the use of the choir, the sum to arise out of the funds of St John of Jerusalem.’[13]

In 1763 Ferdinand Weber was commissioned to provide, ‘Two new stops to be added to the organ … and to remove the furniture stop, which is useless’.[14] And in 1763: ‘Mr William Smith Organist, to agree with Mr Webber, Organ Maker, for a new bellows for the organ of the Cathedral, for giving it thorough cleaning and tuning , and to receive an annual salary for keeping it in order.’[15]

Ferdinand Webber and William Gibson travelled regularly to the provinces tuning and maintaining organs and no doubt supplying instruments to customers. They seem to have been regular visitors to the Cork area – Webber also carried out some work on the organ in Cloyne Cathedral. They didn’t have a monopoly on this work – we read in the Hibernian Chronicle:

At the Assembly-Room in George’s Street For the Benefit of Mr Murdock, Harpsichord-Maker, etc., on Wednesday the 14th July Will be a Grand Ball, by particular desire of his friends to whom he returns his sincere Thanks. Tickets to be had at the Printer’s and at his Lodgings, Charles-street, next to Grattan-street, Hammonds-Marsh. Price 3s 3d. N.B. He tunes and repairs Organs and Harpsichords &c in City and County on the shortest notice and most reasonable Terms.[16]

Murdock was resident in Dublin,[17] but from the above he seems to have been frequently in Cork. At this time also there were at least five musical instrument makers at work in Cork, including one harpsichord maker and probably more.[18] All of which certainly implies a considerable amount of musical activity.

A rather curious announcement appeared in the Chronicle in April 1785:

‘… at the Great Assembly Room George’s street on Wednesday April 27th will be a Grand Concert of Vocal and Instrumental Music in a stile never attempted before conducted by Mr Kotzwara …’.[20]

One wonders what this was about! What was so special about the style that it had never been attempted before? We shall possibly never know for certain. Franz Kotzwara was a Bohemian composer and viola player who was in the orchestra of the Smock-alley Theatre in Dublin.[21] He was given to using kettle drums and trumpets in his compositions so maybe that is a clue as to what the special ‘stile’ was!

Henry De La Main

I have already quoted some of what Crofton Croker had to say about music in Cork. He goes on to mention perhaps the most important musical personality in the city during the final quarter of the century:

… the name of De La Main, many years organist at the Cathedral, ought to be more generally known from the merit of his compositions, particularly his church music, and it is a reproach to Cork that no effort has been made to collect and publish his works.[22]

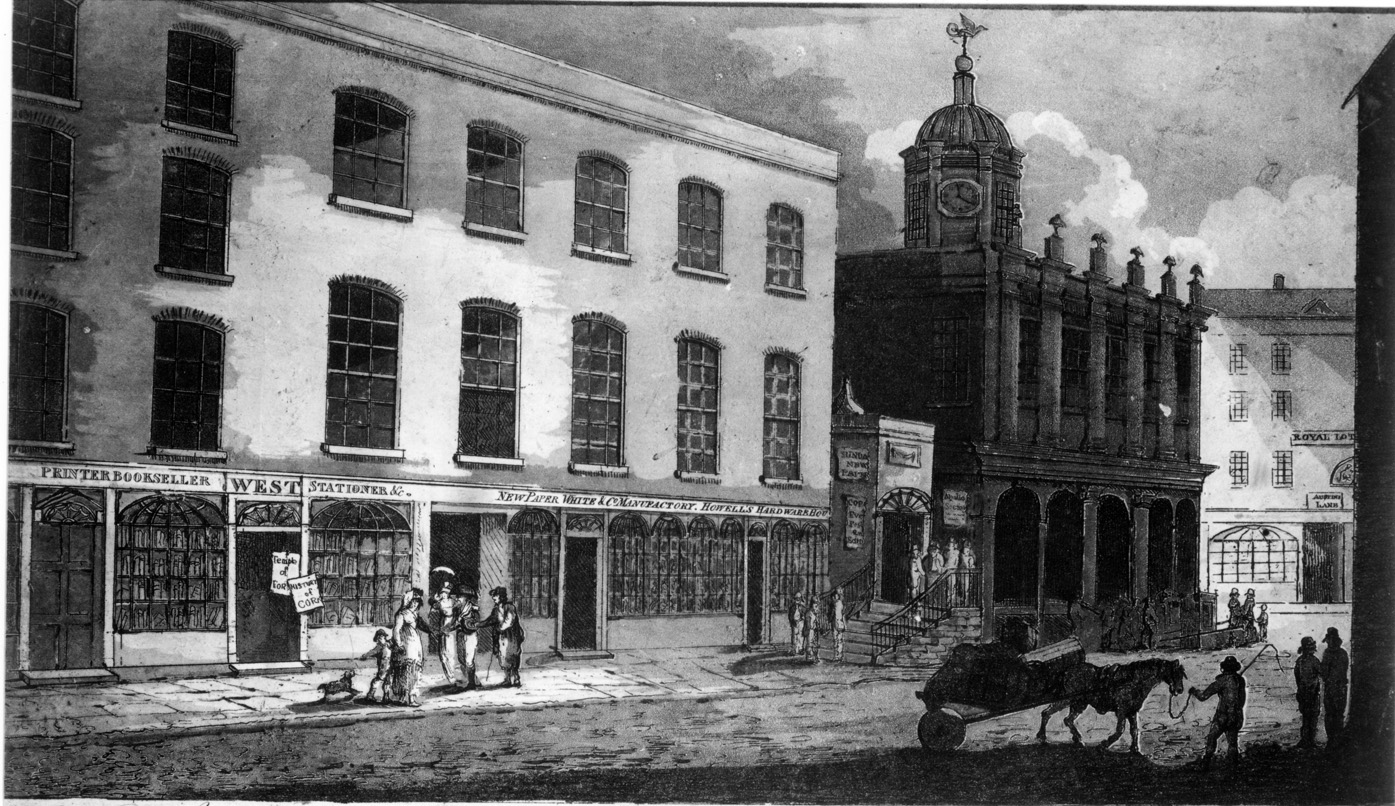

And in William West’s A Directory and Picture of Cork we read: ‘Cork has produced men of talents in many walks of science; in poetry the late Dr De la Cour; in painting the celebrated Barry and in music Delamain led the van.’[23]

Henry De La Main was the son of a French dancing master Laurence De La Main who had settled in Cork, and the family lived on Hop Island (which no doubt took its name from Laurence’s activities…). Henry was made Organist of Christ Church, South Main Street and from there he moved to St Fin Barre’s Cathedral when he was appointed as Organist in 1781, remaining in that post until his death in 1796. Henry De La Main had two musical works published during his lifetime, both, interestingly enough, published in London. The first appeared during his final year at Christ Church and carried the dedication:

To the Reverend Richard Pigott, DD, and the Parishioners of Christ Church in Cork the following Psalm Tunes are most humbly inscribed by their obedient and obliged Servant – Henry De La Main.[24]

These are hymn-like settings of metrical versions of some psalms. The tunes are for the most part undistinguished and the words are in the worst traditions of metrical psalms! The following hideous example is typical:

Our sins (though numberless) in vain

To stop thy flowing mercy try;

Whilst thou o’er look’st the guilty stain

And washest out the crimson dye.

Enough said!

De La Main’s other publication appeared four years later. It was a collection of eight songs scored for voice, two horns, two oboes and strings with alternative versions for voice and keyboard. The publication was announced in the Chronicle:

At the request of some particular Friends Mr De La Main will publish Eight of his Songs in Score – price to subscribers11s 4d one half to be paid on subscribing and the remainder on delivery of the book. Subscriptions will be received by Mr William Flyn near the Exchange. The price to non-subscribers will be 16s 3d.[25]

The following year the Chronicle carried the notice: ‘The Subscribers to Mr De La Main’s Songs are respectfully informed that they are arrived and to be had at the Printers hereof.’[26]

A number of these songs seem to have acquired some degree of popularity, as they were published separately in Dublin.

It seems to me very possible that De La Main was angling for a knighthood because the collection was dedicated ‘To Her Majesty …’ and later in the same year (1785) he composed the music for an Ode addressed to the Duke and Duchess of Rutland, but he was given a considerable snub on this occasion as we read in the Chronicle:

The following Ode written by the Rev. George Sackville Cotter was on Monday last presented to their Graces the Duke and Duchess of Rutland; it was designed for a musical interlude to be composed by Henry De la Main, Esq; and executed by a Vocal and Instrumental Band in presence of the Duke and Duchess, but their Grace’s speedy departure from town prevented the Performance of it.[27]

Here is the opening stanza to give a flavour of the style

‘To sweetly flowing notes attune,

And softly wake the trembling lyre;

Inspiring Muse the festive strain

Enrapture with poetic fire;

From these blest regions far begone,

Heart-rending care, and woe forlorn! Hibernia’s noblest virtues come,

In RUTLAND, great majestic, borne.[28]

That snub to De La Main was repeated a few days later:

On Friday morning last, a grand rehearsal of the Ode addressed to their Graces the Duke and Duchess of Rutland, and set to Music by Henry De La Main Esq; was performed at the Rooms in Tuckey Street. His grace the Lord Lieutenant was expected in town and had his Grace arrived sufficiently early … he could not but have received much pleasure from a piece composed in so masterly a manner. A musical correspondent, who was present at the rehearsal, bears testimony to the great abilities of Mr De La Main in Musical composition: For the grandeur of the choruses, contrasted with the softness of the airs, and the elegance of the recitatives had an effect most striking and agreeable; the whole formed a succession of harmony and melody only to be produced by the skill of a great master … the variety of melodies and changes of modulations throughout the piece were managed in so compleat a manner as to evince, that Mr De La Main’s genius, invention and knowledge of music, are equal to any subject of composition he shall think fit to apply himself to.[29]

So it seems that the Cork public at least was proud of this fine musician, whatever his Grace the Lord Lieutenant might have thought of the matter.

And Thomas Moore, for he was the author of our opening lines, who was his music teacher? Well, of course, it was Philip Cogan, as mentioned in my article ‘Music in 18th-century Dublin’ which appeared in the March/April issue of JMI. I wonder did Cogan often talk at lessons of the concerts of his youth in Cork where there would be ‘after the Concert a BALL.’ Is it too fanciful, I wonder, to think that the idea for the song may have come to Thomas Moore as he remembered the conversations between Phillip Cogan and himself as an impressionable youthful poet those twelve or more years before in Dublin and that ‘The Young May moon’[30] from which the opening lines are taken, may have been the result?

Notes

1. T. Crofton Croker, Researches in the South of Ireland, London, 1824.

2. Charles Smith, The Ancient and Present State of the County and City of Cork, 1750.

3. Anon., Four Letters originally written in French, Relating to the Kingdom of Ireland, Dublin, 1739.

4. Hibernian Chronicle, 11 August 1788.

5. Ibid.

6. Hibernian Chronicle, 18 August 1788.

7. Hibernian Chronicle, 28 October 1790.

8. Richard Caulfield (Dr), Annals of St Fin Barre’s Cathedral, Cork, Cork, 1871.

9. Ibid.

10. The name was sometimes also spelt ‘Kivillie’ in the Chapter Acts.

11. Richard Caulfield (Dr), op. cit.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Hibernian Chronicle, 5 July 1784.

17. John Teahan, ‘A List of Irish Instrument Makers’, Galpin Society Journal XVI, May 1963.

18. Ibid.

20. Hibernian Chronicle, 18 April 1785.

21. Ita M. Hogan, Anglo-Irish Music 1770-1830, Cork, 1966.

22. T. Crofton Croker, op. cit.

23. William West, A Directory and Picture of Cork & its Environs, Cork, 1810. West was a printer.

24. Henry de la Main, Six New Psalm Tunes in Score, London, 1781.

25. Hibernian Chronicle, 29 March 1784.

26. Hibernian Chronicle, 28 February 1785.

27. Hibernian Chronicle, 3 November 1785.

28. Ibid.

29. Hibernian Chronicle, 7 November 1785.

30. Thomas Moore (Musical arrangements by Sir John Stevenson), Irish Melodies Vol. 5, Dublin and London, 1813.

Published on 1 September 2003

Douglas Gunn specialises in early music and is perhaps best known for his work with the Douglas Gunn Ensemble. He has made a special study of music by Irish composers of the 17th and 18th centuries and has arranged, performed and recorded much of Carolan's music. He is also a composer.