A Missionary Spirit

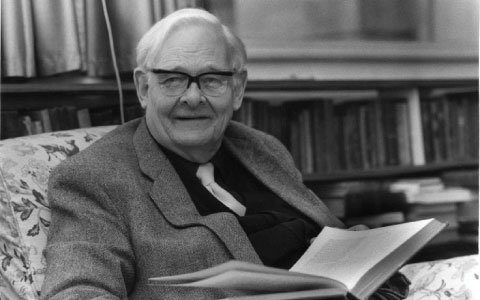

The music critic of the Irish Times 1955–86 was Charles Acton, the last of a family of landed gentry who had owned the Kilmacurragh estate in County Wicklow since the seventeenth century. When he inherited it, after the deaths of his uncle and father in the first World War, it was derelict and mostly due for compulsory purchase under the Land Acts. Like most Anglo-Irish families, the Actons had no place in the new Irish state unless they found it themselves, and, after a few desultory years, Acton found himself appointed music critic of the Irish Times – a way forward into the new Ireland and its artistic milieu which made him a central figure in cultural politics for over thirty years. His views on music (encapsulated in his 1974 lecture ‘A Critic’s Creed’) may answer some of the points raised by Bob Gilmore (‘He’s Just Not That Into You’, Journal of Music, June/July) on the way critics discuss music. Gilmore in particular addressed the issues of qualifications, power, readability and personality, and commented that critics can be predictable, capricious, rigid, pompous or spineless. Acton was, in fact, completely unpredictable, yet trenchant in applying his critical standards, cautious in his opinions, but stiffly ‘protestant’ in speaking his mind.

We must remember that in 1955 the seven-year-old Music Association of Ireland (MAI), with Acton on its Council, was persistently, but not very successfully, arguing the case with government for appropriate facilities for the performance of classical music, for music education and for the building of a national concert and conference centre. The government was largely hostile – or at least indifferent – to the fortunes of classical music, especially since its proponents were members of Acton’s own class – the Anglo-Irish who dominated the early MAI.

When asked what was his principal motive as a critic, Acton answered without hesitation: ‘a missionary spirit – I go to a concert and if I enjoyed it I would want to tell the whole world how marvellous it was, and if I felt they were making a muck of it I would want to tell the whole world it should be better’. It was not necessarily as ‘black and white’ as that suggests, but the declaration conveys the deep-seated commitment of a critic who was passionate about his job. Composer Aloys Fleischmann, one of his sparring partners over the decades (with whom he could be privately very friendly but often disputatious in print) would comment in 1963 that Acton ‘is unusual among music critics in that he writes from the heart as well as from the head’.

This ability to be analytical and at the same time to speak his own mind was Acton’s cardinal virtue and the reason that readers of the Irish Times looked for his opinion. Is there anything wrong with a critic saying that he was in tears as he left a concert, so uplifting was the musical and spiritual experience? And, conversely, is there anything wrong with his saying that he left in a mood of exasperation, so depressing had the performance been? This is the ‘personality’ that Gilmore discusses, and which Acton had in spades.

Acton’s career as a music critic was not merely a matter of attending, and commenting upon, musical performances. Almost immediately after his appointment he was catapulted into the world of cultural politics, and rapidly became a key figure in the ongoing debate about the place of classical music in Irish society. His involvement in musical politics was as a commentator on musical developments, as an instigator of discussion, as a polemicist on behalf of Irish music and musicians – in short, not only the ‘judge’ of events (which is the literal meaning of ‘critic’) but a provocateur and an animateur. ‘I do not believe that music (or any or all of the arts) are a little corner tucked away from the rest of life. If we write as though they were, we will have only ourselves to blame if the philistine politicians treat the arts as of no concern.’

Let’s begin with qualifications: Acton’s school training as a practical musician, his early appreciation of performance, both ‘live’ and on record, his exposure to Richard Strauss and Hans Knappertsbusch in Munich, his reviewing as a student at Cambridge (of Gieseking’s Debussy and the première of Vaughan Williams’s The Poisoned Kiss), his involvement in the organisation of the Dublin Orchestral Players, his close friendship with the budding composer Brian Boydell, his involvement with the fledgling MAI, his experience of concert promotion, all provided him with a foundation of musical experience.

Music critics can, of course, be ‘trained’ in a certain sense, but the extent to which a natural ear for music, or a capacity for expressing one’s feelings about a performance, can be developed by such training is very limited. Acton, like his friends and fellow-critics Desmond Shawe-Taylor and Felix Aprahamian, had a natural aptitude for reaching and expressing his judgements, which no amount of theoretical or academic work could have expanded or deepened. He regarded Dr Geoffrey Bewley, one of his closest friends in later life, as an excellent critic, even though Geoffrey had no musical training whatsoever, but simply because he could express well and cogently a layman’s opinion of what he had heard.

The question of qualifications has always been much debated. In 1974 a reader wrote to the Editor of the Irish Times that Acton ‘was neither a singer nor an instrumentalist, nor had he any kind of a musical degree which, one might expect, would qualify him for this job.’ Acton saw this as an attack on his professional competence and retorted: ‘I do not remember back to when I started playing the piano. I have played a bassoon and percussion in orchestras in Ireland, England and Palestine. For 45 years I have made chamber music, as the occasion arose, on bassoon, clarinet, piano, harpsichord. I have sung in choirs in Ireland, England, Germany, and Palestine, and have been a member of vocal consorts. I have also played slightly, though without proficiency, cello, recorders, horn and organ and entertained friends and relations with solo singing. In addition to that, a musical degree is a hindrance rather than a qualification for the job of critic on a daily newspaper; and my first stint of criticism was forty years ago. Though I have half a century of very wide and fairly deep experience, I emphatically deny that I am an expert.’

Acton came from a family of military men who spoke their mind even while carrying out orders. They could speak sceptically about their governments’ ability to prosecute a war successfully with regard to the men under their command. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that Acton himself was able to detect what he saw as shortcomings in the policies (or lack of them) on foot of which provision for music was pursued. If the hospital conditions in the Crimea (his great-uncle), the questionability of the British presence in India (his grandfather), and the wastage of human resources in the trenches of the first world war (his uncle and father) could all come under the Acton scrutiny, then he – as a practising musician and a well-schooled critic – was in the same vein when he identified and criticised the weaknesses of the government’s attitude to music both broadcast and in performance, and of other agencies, both voluntary and statutory, responsible for music provision and education.

The mere fact that Acton wrote for the Irish Times promoted him immediately into a figure of authority. Many years after his appointment, he would say ‘before I became the Irish Times critic I used to try to put ideas across and all the people said was “That’s only Acton talking”. Since then they have said “The Irish Times says”. Same man, same people, mostly the same things. On the other hand one equally quickly learns that there is no real power (thank goodness) and that those things which you particularly want to result don’t happen, and that the things that you really want to prevent do happen. It’s all fascinating.’ Whether or not he had any ‘real power’, he was perceived, by virtue of his position, as having influence as well as special knowledge.

It was a point to which he would frequently return, especially when advising deputy critics who might enjoy the moment of sitting in judgement. Replying to the Irish composer John Purser, who had stopped short of wishing him ‘more power to your pen’, Acton disavowed any question of power: ‘I agree with you wholeheartedly that no critic should have more power to his pen. I should hope that I might have some influence, that people might use me as a whetstone to their own minds, but not only is power in a critic undesirable in itself, but I am always very well aware of the dictum on power made by my very distant kinsman, the historian’ – he was referring to Lord Acton’s ‘Power tends to corrupt. Absolute power corrupts absolutely’. Later, he was thankful ‘that here we have not got a situation like New York’s where a Clive Barnes has power. I am quite sure (thank goodness) that I have no power.’ (Barnes was the drama and opera critic of the New York Times and later the New York Post.)

When Acton was eleven, his headmaster had said that ‘he has such a curious way of putting people’s “backs up” against him’. Whether liked or not, he was respected for the fact that as a critic, sitting in judgement, and as a journalist whose editor required that he was responsible (in every sense) for selling newspapers, he spoke his mind and did not worry about ‘putting people’s backs up’. After Acton’s retirement, John O’Conor, Director of the RIAM (of which Acton was a Governor for forty-five years) wrote that ‘Of course he could be infuriating at times but there is nobody who can match his experience, enthusiasm, compassion and exuberance’. Those qualities seemed, to this particular musician (with whom Acton crossed swords viciously on one memorable occasion), to be required and respected in a critic: excitement and commitment.

A review of a concert was not only a matter of judging whether the performance was ‘good’ or ‘bad’, pleasing or displeasing, but also a matter of nuance: the structures of musical life and the behaviours of musicians and their facilitators extended far beyond the concert platform and, reading between the lines of the more than 5,500 notices penned by Acton in his career, one learns to appreciate his concern for those structures and the behaviours that occurred within them.

Bob Gilmore mentions the problem of ‘adjectives’ and the difficulty of ‘articulate, intelligent praise’. Sometimes the opposite is the case. Several times, Acton found it painful to have to say that he had not enjoyed a performance by an artist of world calibre. In 1963, for example, a rising star was Luciano Pavarotti, whose voice was giving excitement to talent spotters who gave him his first break at Covent Garden within the year, when he stood in for Giuseppe di Stefano as Rodolfo in Puccini’s La bohème. But for Acton, hearing him as the Duke in the Dublin Grand Opera Society production of Verdi’s Rigoletto, ‘he seemed to have a hard, unsympathetic voice of very little variety… uninspiring’. When he heard Elizabeth Schwarzkopf in 1970, he had loved her voice, but the following year he had, painfully, to put his cards on the table: ‘There is one task which any critic dreads and seeks ways to avoid. That is having to write that a voice is no longer what it was. While last year my writing could bask in her fabulous artistry, this year I could find no way out of noting that the artistry is no longer wholly supported by the glorious voice itself.’

Acton summed up his position in terms with which, I think, Bob Gilmore would agree: ‘There is no such thing as an objective value judgement of a performance. All criticism is subjective. All criticism is a matter of opinion and it is for opinion that a critic is paid’, he wrote in 1972. All reviews implicitly begin with the words ‘In my opinion…’ since – whatever his or her qualifications – the critic merely conveys to his or her readers the impression made by the performance. A critic ‘must know why he disliked a concert but he needn’t necessarily say so’, Acton said in interview with me; but he should always include the word ‘I’, ‘to emphasise to the reader that it is one person’s opinion only’.

As he would write very early in his career, ‘Criticism is of course a very subjective thing and is always a personal opinion; but I do try to be constructive, to encourage rather than discourage, and to be some help to music and musicians’. In ‘A Critic’s Creed’ Acton would write, crucially, that ‘no one can really get outside his personality’; in the same breath he admitted to a dislike of Mascagni and Menotti, and he might as well have added his famously low opinion of the Schumann cello concerto and the Chopin piano concertos (‘I’ve had the experience of playing the bassoon in the Chopin concertos….’): the point being that to review these works involved, as far as possible, putting aside one’s personal prejudices.

The critic is also, of course, the arbiter of fact: did the performer play the composer’s ‘repeats’; did the singers carry naked flames on the operatic stage; was the piano a Steinway or a Yamaha; did the players use music or did they play from memory? But the role of the critic is principally as the arbiter of taste: was the performance pleasing to the ear; was the operatic mise-en-scène pleasing to the eye; did the premiere performance of this work add significantly to the body of Irish compositions, and should it be heard again; did the critic agree with the level of the audience’s applause; did this coming-out recital by a young debutant convince that they are ready for a professional career? Not only was a review subjective, but, allowing for stage nervousness, particularly at a ‘coming-out’ recital, there was also the question of the performer’s health on the night, the critic’s own state of mind, and the key factor in critical subjectivity: intuition, the means by which messages pass from one hemisphere of the critic’s brain to the other.

Writing to a friend in 1961, Acton succinctly reflected on his personal modus operandi and the perception of him by his readers: ‘I often realise afterwards that I have been too lenient; not yet that I have been too severe.’ This would hardly have been the opinion of those who received his critical disapproval, especially of the type ‘She is not yet ready to launch herself on a professional career’ – a judgement which I know to have pained him when he critiqued a debut recital. ‘My notices are mildness itself compared with those of my colleagues in other capital cities. Comments on my notices tend to divide themselves into two distinct types: (a) the majority who write “why were you so kind…?” and (b) the minority whose sisters, cousins, aunts were performing who write “This concert was perfect, how dare you say anything else?” Vitally and fundamentally, I write for the thousands of people who read the paper and who may (as some do) write in and say: “On the recommendation of the Irish Times I spent £1 going with my wife to…. The performance was not worth £1 which I feel to have been ill-spent”. One of the questions the critic must ask is “Is this performance worth the money asked of the cash customer?”’

The responsibility to the reader of the newspaper for which one worked was almost as important as the responsibility to the craft and cause of music itself. Acton’s chief disappointment in retirement was that his successor did not take up the active promulgation of musical causes. Perhaps the environment has changed and a music critic is no longer needed to enter the marketplace but merely to sit in refined judgement.

Quotations from conversations between Acton and the author are taken from three radio interviews on an RTÉ Radio FM3 broadcast in 1990.

Published on 1 August 2009

Richard Pine, Director of the Durrell School of Corfu, is a former Concerts Manager in RTÉ. He is the author and editor of books on Irish music history and of definitive studies of Oscar Wilde, Brian Friel and Lawrence Durrell.