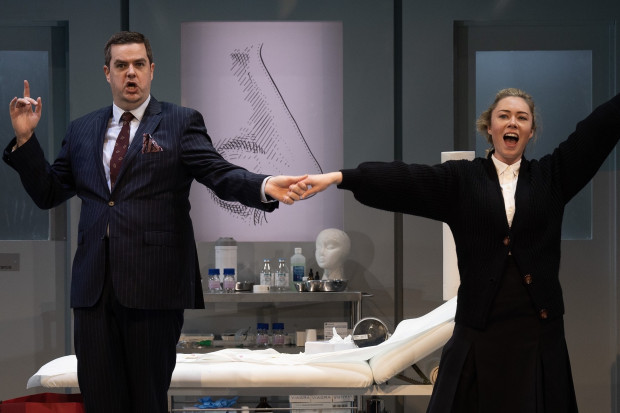

The Irish Baroque Orchestra (Photo: Sarah Doyle)

Lesser-known Pathways of the Baroque in Ireland

Period instrument performance has never made a secure inroad in Ireland. In the past Irish Baroque Orchestra seemed to hold a peripheral position on the Irish music scene, its members spending most of the year working for other ensembles, with the whole thing kept financially afloat by an unending stream of performances of Handel’s Messiah, for which admittedly there is an endless supply of audience members. However, since Peter Whelan took up the position of artistic director in 2018, there has been a concerted effort to root the orchestra more strongly in the local, resulting in an exploration of music that would have been heard in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dublin. Two CDs have already appeared; the first focussed on the English-born composer and violinist Matthew Dubourg (1703–67) and the second around the Italian castrato Giusto Fernando Tenducci (1735–90), whose personal life titillated eighteenth-century Ireland and later inspired the libretto of Gerald Barry’s The Intelligence Park.

The third CD, The Hibernian Muse – Music for Ireland by Purcell and Cousser, takes two pieces of the ceremonial music that formed the aural background to the power structures of the ruling class. The first piece on the disc is an ode commissioned to mark the centenary of the matriculation of the first students from Trinity College Dublin in 1694. The text was by the British Poet Laureate Nahum Tate (1652–1715), a Dublin-born Trinity graduate, and it is presumed that he was responsible for persuading his frequent collaborator Henry Purcell to provide the music. Great Parent, Hail has had almost universal bad press from Purcell scholars and musicians, and as far as I am aware has only been recorded once before, as part of Robert King’s complete recording of Purcell’s Odes on Hyperion. In 11 short sections, with a mix of arias, duets and choruses, the piece lasts less than 25 minutes.

Certainly if one compares it with the work Tate and Purcell produced for Queen Mary just a few weeks later, Come ye sons of art, one can see why. One of its fundamental problems is also very clear. Whatever Tate thought of his time at Trinity, it certainly did not inspire him to any great heights and one can imagine Purcell sighing to himself as he tried to find a way to set such lines as:

Succeeding princes next recite:

With never dying verse requite

Those favours they did show’r;

‘Tis that alone can do ‘em right;

To save ‘em from oblivion’s night

Is only in the Muses pow’r.

Purcell shows considerable rhythmic inventiveness in his setting of the rather leaden text, though his penchant for word painting doesn’t always help matters. The persistent repetition of the word ‘repeated’ in the duet ‘After war’s alarms repeated’ is both obvious and somewhat tiresome, particularly when this is followed by the unfortunately titled aria ‘Awful matron take thy seat’ which ends with the words ‘Songs for Phaebus to repeat’ triggering more verbal reiteration. The sudden burst of chromaticism in the opening chorus for the line ‘Who hast thro’ last distress survived’ is a striking musical effect, particularly after music that has emphasised simple diatonic arpeggios, imitative of trumpet writing, but it seems somewhat out of scale for the context. In fact, so extreme is the contrast between the first and second lines of the chorus that it reminds one of the satirical use of chromaticism in comic Baroque pieces. One feels it would have worked more effectively if the movement had been on a somewhat larger scale. Indeed, from the insubstantial overture to the short-winded final chorus, most of the ode seems underdeveloped. In the liner notes, Samantha Owens suggests that Purcell may have been writing ‘somewhat cautiously’ as he would not have known the performers or what standards in Dublin were like. However, as Purcell was not at the performance and it was taking place far away from his central source of income, perhaps it was just a rush job.

I don’t want to suggest that the piece is a write-off however. It does contain music of high enough quality to sustain interest for its short duration, and in the aria ‘Another century commencing’, mellifluously sung by Anthony Gregory, a real Purcell gem. As for the performance, one might quibble with some of the details – the performance of ‘But chiefly recommend to fame’ is perhaps a bit too jaunty for what is meant to be a tribute to William and Mary and the fussy diminuendo in the opening series of ‘hails’ rather undermines the intended effect – but overall it makes the best case possible for the piece and provides a more characterful and ebullient performance than its rival on Hyperion.

Patriotism

Whelan does Purcell a further favour by coupling it with the substantially longer and less inspired The Universal Applause of Mount Parnassus by Johann Sigismund Cousser (1660–1727). Purcell’s ode, ostensibly celebrating Trinity College, was primarily a statement of political loyalty to William III in the wake of the Battle of the Boyne, with the chorus noting ‘surely no Hibernian muse / (Whose isle to him, her freedom owes) / Can her restorer’s praise refuse / while Boyne and Shannon flows.’ Cousser’s ode is more direct in its patriotism, having been composed for celebrations of Queen Anne’s birthday at Dublin Castle in 1711. Once again, the text is patriotic hackwork with the muses singing vaguely about Anne’s achievements in verses such as:

Anne’s deathless acts rehearsing

Crowded annals can’t contain.

Fame will ever be dispersing,

All the wonders of her age.

Considering the unpopularity of the War of Spanish Succession in Britain at this time it is interesting how much of the ode is given over to celebrations of war (‘the bold Britons from the field when returned / show their great valour by glorious scars’). A curious balance is struck between Anne as valiant warrior and a more traditional view of Anne (and women more generally) as sexual objects that are just as perilous as soldiers:

Great Britannia as much is admired,

for her bright ladies as conquering arms.

Beauty desired,

passion inspired,

e’er will be filling the world with alarms.

The work’s nine solo soprano parts are distributed among three singers, Maria Keohane, Aisling Kenny and Sinéad O’Kelly, who all do their utmost to invest their various arias with interest, while Whelan draws stylish and energetic performances from the orchestra and Belfast choir Sestina. It all makes for fairly pleasant background Gebrauchsmusik if one doesn’t listen too carefully. However, an attentive listen highlights the melodic poverty of the piece. The ground ‘No other, than immortal lays’ demonstrates Cousser’s gravitation to the conventional and his lack of invention in a form that potentially gives a first-rate composer a chance to really shine. Other arias such as ‘Our Britain never gained’ or ‘Fortune caressing’ seem to contain little more than application of the most rudimentary vocal line to a chosen bass line. The CD is rounded out by a gutsy performance of ‘Sín síos suas liom’ by Aisling Kenny, as if to highlight the distance between the Dublin court and the rest of the country.

Overall, this is an enterprising disc that will appeal to any listener who is interested in exploring some of the lesser-known pathways in Baroque music, while not being too worried if some of the music is (as might be expected) somewhat pedestrian. It is also an essential purchase for Purcellians interested in hearing the best case being made for this overlooked ode. The disc is invaluable for anyone interested in this period of Dublin’s history and for any post-colonial historians interested in exploring the projection of the monarch’s position in the peripheries of empire. Together with IBO’s other discs we are beginning to get a real sense of what music making was like in the capital in the era prior to the Act of Union.

The Hibernian Muse – Music for Ireland by Purcell and Cousser by the Irish Baroque Orchestra, Peter Whelan and Sestina is released on Linn records. Visit www.linnrecords.com.

Published on 13 December 2022

Mark Fitzgerald is a Senior Lecturer at TU Dublin Conservatoire.