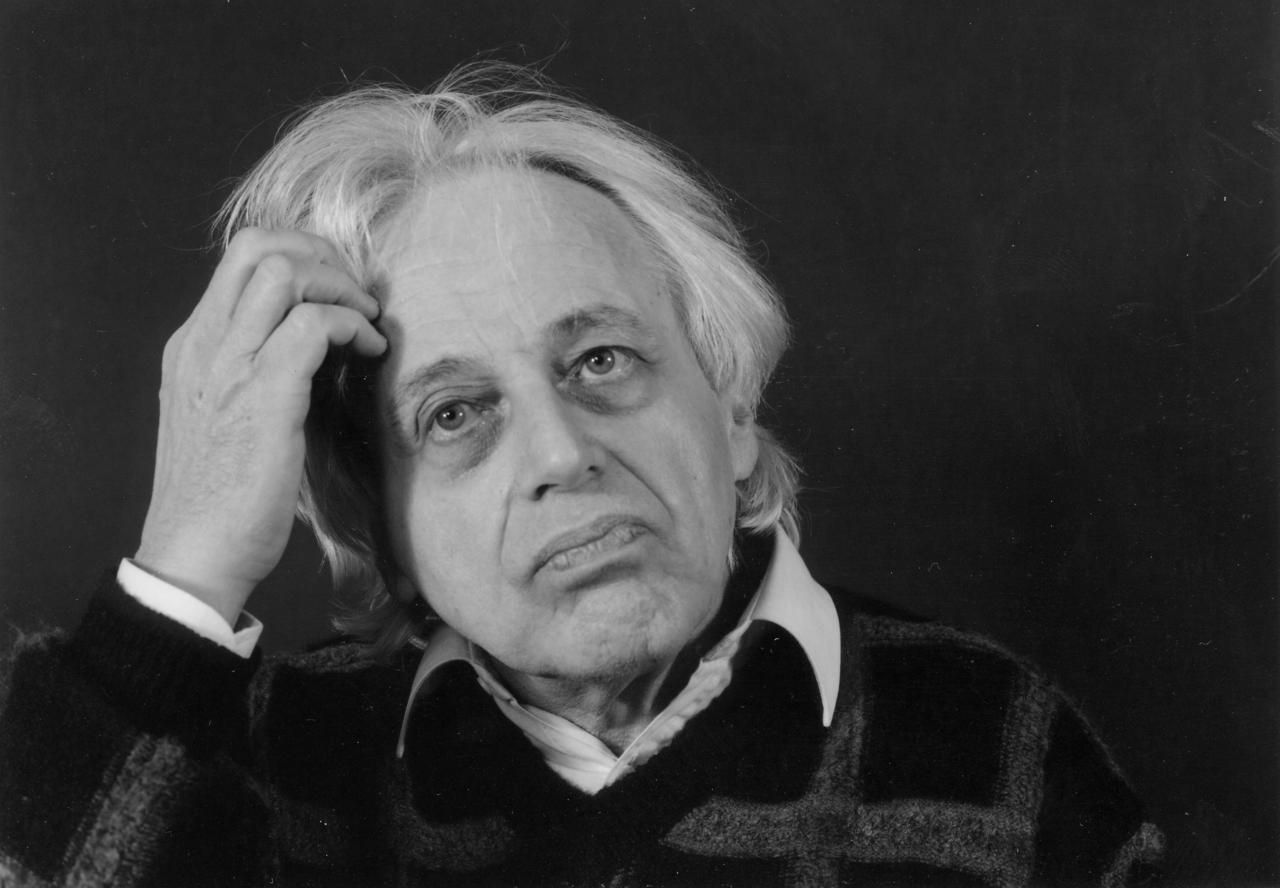

György Ligeti

Laughing at the Chaos: György Ligeti (1923–2006)

Well before he died in June 2006, György Ligeti was casting a long shadow. His compositions are the subject of an ever-growing canon of critical response, interpretation and commentary. This is because the expansive reach of his musical meanings connects to the most deeply felt regions of contemporary sensibility and psychology – the chaos, the confusion, the contradiction, the humour and, yes, the absurdity of it all.

For almost fifty years Ligeti produced music which quite simply thwarted classification. In 1956 he secretly crossed the border to escape the Communist grip on Hungary and since then spent the majority of his composing life skipping the borders between zealously guarded methods and genres. Despite his ambivalence to creed, there is little that is eclectic about the complex internal unity, the deep structure of his work, regardless of the various and diverse processes behind which that unity seeks to hide. And yet, Ligeti’s refusal to be typecast has probably, if unintentionally, nurtured the pluralistic cultural trends of recent years.

So what characterises Ligeti’s music? Contradiction is a central facet. His obsession with clocks and clouds exposes an equal, if implausible, fascination with both precision and imprecision. Darker mises-en-scène already imagined by Breughel and Bosch provide the perfect backdrop to Ligeti’s proclivity for ghoulish grotesquerie (Le Grand Macabre, L’escalier du diable). Absurdity is perennial in his work – Aventures and Nouvelles aventures compact a vast array of human expression into an hilarious orgy of eccentricity, fast-forwarded to catapult music to the verge of sanity, and often beyond. The wonderlands of Alice and Escher provide alternative scapes where quirky inanity, illusion and folly are a given – and have full credibility (Nonsense Madrigals). Ligeti’s perspective is askew, his architectural eye is that of a Gaudí, his musical ear will bend the canonic to fit his oblique and sometimes devious vision (Désordre). Indeed, many of his mechanico-rhythmic works (É) seem to self-destruct like those collapsing composites of Jean Tinguely which shake and gyrate themselves to rubble. The self-destructive aspect in Ligeti’s music may be seen as inherently negative (a criticism of Michael Finnissy), but it does highlight his acutely critical, if sardonically wry, response to illusions of permanence. He is, in this sense, a zany anarchist.

But not all is outré and playful. There is a deadly seriousness to his Requiem unmatched in the latter half of twentieth century music that only a ‘survivor’ could manage to compose, or earn the right to. Most probably a reaction to his early, tragic experience of fascist and Communist oppression (the former under which he lost both brother and father, the latter under which he lost artistic freedom), Ligeti, always l’étranger, was never to affiliate himself to any ideology, political or musical. For certain, his rejection, even abhorrence, of the ‘club’ ran deep. In fact, his whole artistic impulse was to subvert accepted wisdom, regardless of its trend value.

It is not surprising, therefore, that early on he would defend Bartók from accusations of reactionism – ‘Bartók’s rigorous, tonal language is not classical […] his language is a phenomenon […] not a “return to tonality” but rather a “progress to tonality.”’ (Neue Musik in Ungarn, Melos, 1949). Having been accepted into the notoriously impenetrable clique of the Darmstadt circle in 1957, Ligeti, in an essay for Die Reihe (The Row), immediately set about exposing the mathematical ‘flaws’ in Boulez’s Structures Ia and highlighted ‘fields of inexactness’ and oversights in serial fidelity. In 1963 he scandalised the city council of Hilversum (Holland) with the world première of the brazenly provocative Poème Symponique for 100 metronomes. The scheduled television broadcast of the filmed event was cancelled at the urgent insistence of the Hilversum Senate! In 1982 it was the turn of the avant-garde establishment to be outraged with the appearance of his Horn Trio, a work which invited, again, into his musical language a distinct narrative line. An audacious Homage à Brahms (but owing more to Beethoven), the Trio exemplifies Ligeti’s concept of a ‘progress to tonality’ or, at the very least, an acceptance of tonality as a still valuable antecedent. It led to attacks by, among others, Helmut Lachenmann.

Despite the apparent outward eclecticism of Ligeti’s works, there is one consistent aspect which can be observed right throughout the complete œuvre. A concern for the autonomous line can be traced (surprisingly) from his early ground-breaking studies in pure, dense texture like Atmospheres and Lontano through the middle-period complexities such as San Francisco Polyphony (not so surprisingly), to the more recent Violin Concerto, the virtuosic characteristics of which rely, practically, on ‘soloists’ within the orchestra itself.

The ‘soloistic’ parts in Lontano immediately demonstrate the dichotomies inherent in Ligeti’s music. Almost throughout the score, each instrument has its individual line with very specific and detailed instructions. Perhaps in emulation of the highly developed contrapuntalism of the fifteenth-century Franco-Flemish School brought to perfection by Johannes Ockeghem (1410–1497), Ligeti conjured up a 56-voice canon in Atmospheres, surpassing even Penderecki’s Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima as the major classic of the texturalist school. These scores are richly intricate, multi-voiced schemata but the outcome is a saturated diffusion of sound. Polyphony is written, a strange Rothkoesque harmony is the result. The incredible detail has to be seen to be believed – it certainly won’t be heard! However, the minute sinews do control the inner shiftings of the music, the subtlest of shade changes making these texture studies the most exquisite of the genre. This is only possible because Ligeti’s ear for timbre was second to none, his ability to differentiate between textural delicacies was extraordinary.

But there is a further conceit in Ligeti’s play of voice and texture and it lies at the very heart of his music. It is a preoccupation with subliminal effect and the creation of illusion. Lontano is written in equal temperament throughout, but its density of polyphony contrives to neutralise any tonal characteristics. From knowledge he gained in the studio, Ligeti quite simply deconstructed the building blocks of music (timbre, partials, raw sound, texture, harmonics, the harmonic series, etc.) and then reconstructed them, but this time for the orchestra, and so in Apparitions we have the impression that we are listening to some giant electro-acoustic work. In both cases, the result is an illusion of sounds. Here we have the curious world of Alice subsumed completely into an abstract system for composition.

Ligeti’s obsession with differentiated voices within the context of larger structural complexes is so prevalent it should perhaps not come as a surprise that, from the Horn Trio onwards, the previously hidden voices mutate into a fully developed leitmotif. The so-called lamentoso music comprises a short series of three (mostly) descending lines – in the first phrase the opening interval is a minor third while the rest descends in semi-tones, the second line is longer than the first, the third longer again. The lamento motif can, therefore, be seen as a genetic blueprint, the full and open acceptance of the line Ligeti had been keeping buried deep within the dense timbral masses of the 1960s and the highly populated polyphonies of the 1970s. But in the Horn Trio the line emerges truly autonomous and exposed. It will be a seminal feature, a Ligetian fingerprint in many works to follow – the É, the Violin Concerto, the Piano Concerto, the Horn Concerto, and, in his penultimate work, Síppal, Dobbel, Nádihhegedüval. In this sense, Ligeti’s progress as a composer may be viewed as an attempt to work his way out of muddied textures towards the clarity of a single voice, a leitmotif that would come to embody the very nature of his musical genetics.

Ligeti stands alongside Stravinsky and Wagner as perhaps one of the few composers to have made major stylistic changes late in life. But this transformation in his music is concerned with more than the reappraisal of tonal procedures. The revised appreciation of tonality not only allowed him to flirt with jazz and embrace a new, luscious sensuality (Cordes à vide, Arc-en-ciel) but ultimately re-admitted back into his late music a Hungarian/Romanian folk element which had been held at bay for decades (Sonata for Viola). But most significantly, the stylistic change, which notably allowed Ligeti to continue his preservation of the line, is essentially a shift in attention from matters of timbre, harmonic web structures and massed polyphony towards concerns of a rhythmic nature. A piece which is pivotal in this re-direction is the previously discussed Poème Symponique. The work, which has been relegated by many commentators to the level of mere experimental pun or, at best, a typical Ligetian coup de theatre, in fact demonstrates most aptly his shift from the timbral world to the rhythmic. It starts as an unyieldingly textural study and transforms itself into a series of superimposed distinct polyrhythmic entities, reducing finally to one stuttering hesitant, but uncluttered voice. Poème Symponique, therefore, epitomises the ‘modulation’ Ligeti subjected his music to in order to find a new process which allowed him to continue his micro-polyphonic urges within a new, richly stratified and rhythmically-driven context. The individual lineal fibres which were once at the service of creating canvasses of pure cauterised harmony are now intricately woven into playful mechanico-rhythmic constructs derived from the absorption of a surprisingly broad spectrum of influences including American minimalism, fractal geometry, the constructivist works of Conlon Nancarrow, and ethnic central African and east Asian musics.

One final contradiction. Ligeti’s broad inclusiveness in relation to what he permitted as influence is matched only by the rigorous exclusion of what he considered unnecessary to his fundamentally sparse, Beckettian palette. His genius economised, his finely tuned ear always pared his musical material down to the very essentials, hence the long gestation of his compositional process and the patient re-drafting of many works. Quite uniquely in contemporary music, he never wrote more than he heard – an approach that was all in the cause of an old-fashioned concept called craft. This is why, despite the clocks running fast, or the creeping disorder of his mechanical fabrications, or the absurd tongue-in-cheek self-deprecation, or the hall of mirrors used to contort his aural illusions, Ligeti’s music works. He does not dispel the chaos and absurdity of contemporary life, but, like Beckett, he helps us laugh at it.

Published on 1 September 2007

Benjamin Dwyer is a guitarist and composer and the author of 'Different Voices: Irish Music and Music in Ireland'. He is Professor of Music at Middlesex University's Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries.