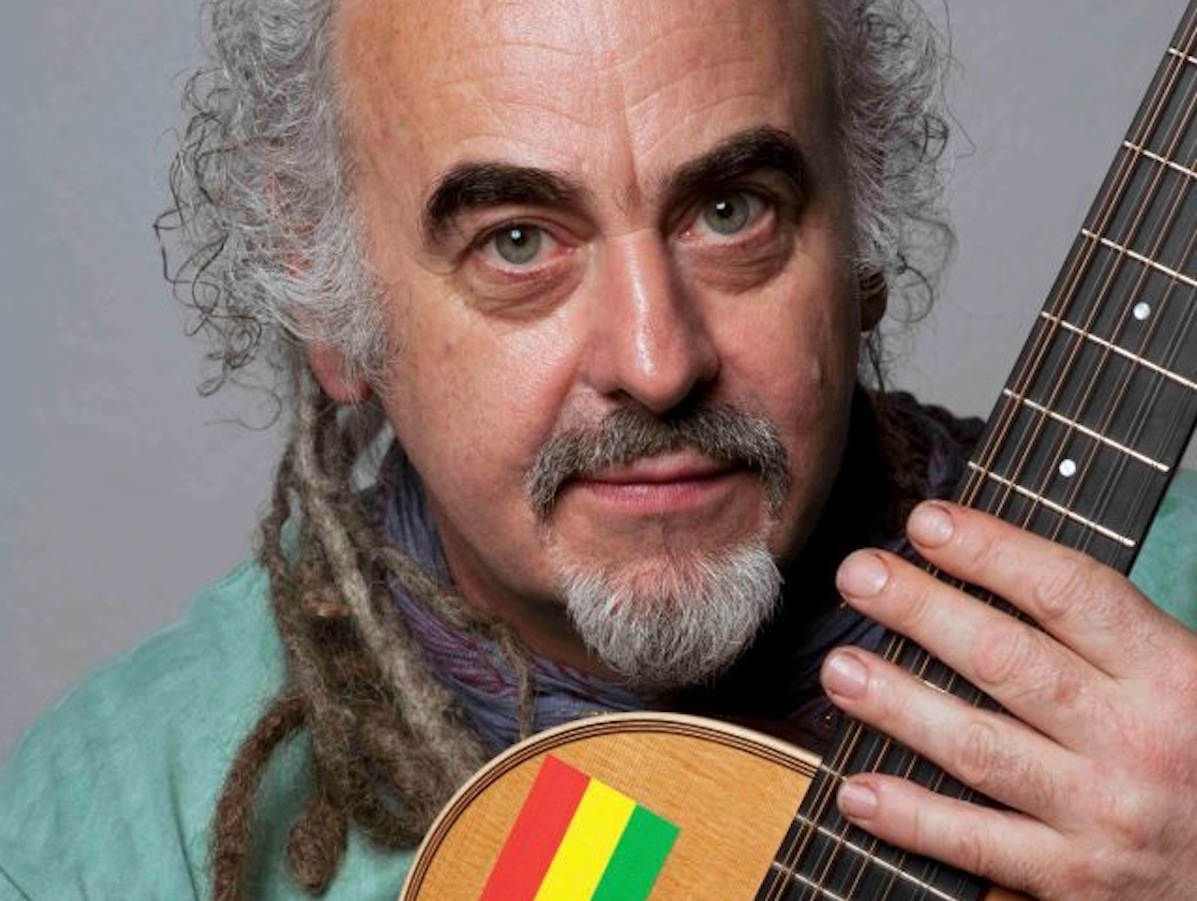

Steve Cooney

Just Cooney

Though we’re still a long way off Joe Brennan’s AD 2490 and the complete eradication of guitaricism, there may already be an ‘accepted style of playing traditional Irish guitar’. Players such as Dáithí Sproule, Arty McGlynn, Paul Brady, Dónal Lunny, Dennis Cahill, John Doyle and Steve Cooney have made the guitar such a central force in the playing of Irish traditional music in so many contexts, there are few who would deny its place, at least as played by such masters. Interestingly, two of those guitarists came to the music from well outside the tradition: Dennis Cahill and Steve Cooney.

Unusually for a musician, Steve Cooney does not have a website, a MySpace or a Facebook presence, and perhaps uniquely for someone so significant in the music’s recent history, there is, intentionally, it would seem, no entry for him in Wikipedia. This fits in with his non-conformist outlook on the world, and makes tracking his output down the years quite involved.

What we can say, with some uncertainty, is that Steve Cooney came to Ireland from Australia sometime around 1980 or 1981. He was inspired to do so after travelling to the Northern Territory of his homeland to learn the ditjeridú (didgeridoo), only to be encouraged by the Aboriginal elders he met there to travel back to Ireland to learn about his own indigenous culture — he has Tipperary and Cavan ancestry.

Although he is known to us now mostly as an acoustic guitarist, in those days he was more likely to be heard playing bass guitar, and indeed through the 1980s he toured and recorded with Stockton’s Wing as bass player in a kind of transitional period. (He wrote the reel ‘Skidoo’ that was central to their live performances, and which was later recorded by Sharon Shannon on her first album.)

The deeper engagement with indigenous Irish culture came when he moved to Dingle in the late 1980s, in order to immerse himself in the music of west Kerry. He did that with the help of the accordionist and singer Séamus Begley, and appears on Begley’s 1989 duet album with his sister, Máire, Plancstaí Bhaile na Buc, accompanying on guitar and piano.

The following year he and Begley worked on an album together produced by Mike Scott of the Waterboys. ‘They made brilliant, fiery music, breakneck polkas as tough as punk rock and hypnotic hornpipes punctuated by Cooney’s Spanish guitar rallies and sudden dizzy runs of Broadway jazz chords,’ writes Scott. ‘Then they would shift gear in a nanosecond for Begley to sing a song as elegant as an Elizabethan madrigal.’ But this album was never released: ‘The music he and Begley recorded that September — as raw, majestic and magnificent as the landscape in which it was made — remains unheard.’ A different album with Begley, Meitheal, was to appear in 1996, capturing, particularly in the last live track, something of the roof-lifting sound that was so popular with dancers. Though they never formalised a name, their reputation was such that ‘Cooney and Begley’ developed the ring of brand.

Through the 1990s Cooney practised a kind of recording and gigging nomadism, working with a breathtaking range of musicians and bands, including Sharon Shannon, Altan, Liam O’Flynn, Laoise Kelly, Sliabh Notes, to name only a few.

In 1995 he recorded with Martin Hayes on a number of tracks on the latter’s Under the Moon album, and toured with him. Hayes recalls: ‘When I first started doing tours in Ireland I had the opportunity to play many gigs with Steve. I’d never played with anyone as spontaneous and in the moment. It was like playing with a mind reader, he instinctively understood the feeling and rhythm of the East Clare music I was trying to play. He only plays music from his heart.’ His spirit of musical adventuring has not ceased and in more recent years he has played an important role in the work of artists such as Andy Irvine, Noel Hill, Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin, Sinéad O’Connor and Luka Bloom.

Tony MacMahon describes his collaborative work as ‘an orgy of good-will’. ‘I have never, in my life,’ he says, ‘met a person of his generosity of spirit. He has spent thirty years lending his prodigious musical talents, often taking a backseat… thirty years a-giving.’

Bloom suggests that in relation to the guitar there are two periods in Irish music: ‘before Steve and since Steve. Before Steve the guitar struggled to come to terms with the intricacies and the flow of Irish music. Often guitar players would play along with music, having no real feel for it or understanding of it. Steve has always come to the music from a place of deep respect and love.

It’s not that he’s a great guitar player, though he is. It’s his spirit, his nature. His playing really brings to life all the joy and beauty in the music. Everything is enhanced. Everything is deep, everything matters, and it’s all great fun.’

Playing acoustic guitar, complete with gaping hole in it, and often bare foot, it wasn’t just his eclectic virtuosity and harmonic freedom that impressed these esteemed musicians. Cooney’s percussive style brought something new to their music. (‘He continues to inspire me,’ says Bloom.) While the likes of Paul Brady (on, for example, Matt Molloy, Tommy Peoples, Paul Brady) anticipates the style, Cooney consolidates its relationship with the music more widely and deeply. ‘It would appear,’ Bloom realises, ‘he has inspired a whole generation of Irish guitarists’ – no doubt with players such as Gavin Ralston and Tim Edey in mind.

Through all this guesting and producing and nurturing, Cooney was also writing music, some of which has been recorded by the likes of Altan, Mary Black, Seán Smyth, and Andy Irvine. Cooney was also always interested in pedagogy, which is reflected in his important contribution to the music for the educational books Rabhlaí Rabhlaí and Scéilín ó Bhéilín (from Oidhreacht Chorca Dhuibhne), and has culminated in his development of a more intuitive musical notation designed to enhance music learning in schools. For this work he recently received a Masters of Literature in Education from UCD and has embarked now on PhD research with SMARTlab there.

He has had a long association with the traditional music collector Canon Goodman’s music, and he is recognised as an authority on the subject. In 1993 he performed a concert of Goodman pieces with Odhrán Ó Casaide to mark the opening of the Great Blasket centre in Dunquin, the first time some of those tunes were heard publicly in Goodman’s native west Kerry in over 100 years.

Less well known is his political side, which can be observed in the biting wit of his satiric poetry, but which has most comprehensively been expressed in his spearheading the establishment in 2001 of FACÉ (Filí, Amhráinithe agus Ceoltóirí na h-Éireann), a network of traditional musicians, singers and poets striving, as he wrote himself in The Journal of Music ‘to expand the number of venues where traditional musicians are welcome to play in sessions, encourage venues to treat musicians fairly, help with teaching and learning, provide recording experience for those who wish to make CDs, and provide a resource centre – our developing web-site – with all its related links. We can all, professional and non-professional alike, bring about positive change by channelling our creative energies in a united way.’

These days, Cooney continues to perform with his many musical friends. He joined Rónán Ó Snodaigh on stage in Whelan’s recently in the first of a series of concerts revisiting Ó Snodaigh’s solo albums. Meanwhile, he and Tony MacMahon have been reviving an older mode of performing traditional music: playing by invitation in people’s kitchens for private audiences. (A recording of a concert they did together in Éigse an Spidéil in the mid-2000s remains unreleased.) MacMahon feels Cooney represents ‘the best-kept set of secrets in the wide world of music played in Ireland today. Though he has played and recorded with the great and the good of Irish music for thirty years, I have met only a few who have been exposed to the full spectrum of his knowledge of music, his spiritual passion in performance, his purity of thought in relation to our human condition, in all its weakness and greatness.’

He is currently recording an album of traditional songs with Iarla Ó Lionáird, who describes Cooney, a longtime friend, as ‘a different kind of musician than any other I have encountered. Genuinely in touch with the spiritual in our music though having come to it later in life, he is to me less an accompanist and more a musical companion in the truest sense. Speaking as a singer, he is the perfect travelling friend, the best foil to my excesses, the surest navigator of every curve, lift and dive that a song can bring us on in a musical performance. He believes in the beauty and importance of our old music and as a co performer of that music he is matchless in his sense of anticipation, his genuine depth of feeling and the obvious brilliance of his skill and technique. He is of course also a composer and interpreter of the highest order in his own right, from Dowland to O’Carolan from Hendrix to Goodman; he feels the music in a total sense and with a degree of measured abandon that can lift any performance into new realms. He is a dreamer journeyman, and they (an elite grouping) have always made the best musicians.’

Christy Moore concurs: ‘Every time I sing with Steve Cooney he brings a new dimension, a fresh colour to the song we are playing. In a life devoted to music he has become an important presence in the culture of Ireland. He is an exciting and highly accomplished musician.’

Amazingly, Cooney hasn’t been a member of a band since the 1980s and has never released a solo album. However, on Sunday, 30 September, in Vicar Street, Dublin, Conor Byrne and Harmonic Productions present the first concert of Steve Cooney’s new band Éiníní — featuring Rod McVey (keyboards), Joe Csibi (bass), Odhrán Ó Casaide (fiddle) and two percussionists, Robbie Harris and Robbie Perry. The concert is both a celebration of Cooney’s contribution to music in Ireland (with guest musicians, including Christy Moore, Dermot Byrne, Iarla Ó Lionáird, Luka Bloom, Mary Black, Tony MacMahon, Tommy Sands, and Vinnie Kilduff, lined up to join him) and a preview of Éiníní’s forthcoming album Rhapsody and Rascality.

MacMahon wishes to make a prediction: ‘Steve Cooney’s new band will rise up among us, as Ceoltoiri Chualann did fifty years ago, to create a new vision of beauty and tenderness in music. That it will be done using electric instruments will make this revolution all the more astonishing.’

Tickets for the Vicar Street gig are on sale from Ticketmaster.

Published on 18 September 2012