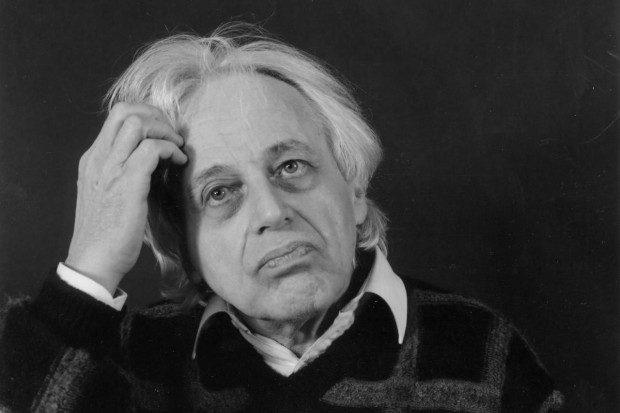

James Wilson (© Contemporary Music Centre)

James Wilson's Inexplicable Decision

‘How many pieces by Jim Wilson have been performed since he died? None. Because he’s not alive to go screaming and shouting for his music to be played. There are no curators anymore,’ Jane O’Leary observed in a recent interview I conducted with her. I was reminded again of her frank statement while reading The Life and Music of James Wilson by Mark Fitzgerald, which was published this year by Cork University Press. Fitzgerald has been making important contributions to Irish musicology in recent years, not least for his co-editing (alongside John O’Flynn) of Music and Identity in Ireland and Beyond (Ashgate, 2014), which refreshingly opens up the boundaries of musicological investigation in Ireland.

But for problems connected to a previous edited series to which it was initially attached, The Life and Music of James Wilson would have appeared years ago. It is nonetheless a welcome if belated addition to the growing, though by no means exhaustive, research into music in Ireland from the post-war period to the present. Any book that attempts to address the development of classical/contemporary music in Ireland over the past one-hundred years has to contend on the one hand with the broad failure of government policy to create a healthy musical infrastructure, and on the other, the varying degrees of success that individual composers have had in trying to pave a way forward in that unpropitious environment. Wilson’s unflagging attempts to exist as a composer in unfavourable conditions becomes a dominant feature of this book.

Fitzgerald balances a fascinating overview of Wilson’s life with examinations of key works in a fluid and stylish manner that makes for interesting reading. He never allows his descriptive analyses to overstay their welcome and has a fine knack for telling us just what we need to know – which means not everything that he knows. As becomes apparent in the book’s conclusion, Wilson’s decision to move from London – one of the most active centres in Europe for music after the war – to Ireland, a country that still fails to adequately support musical culture, had a deep impact on his output and its reception. This becomes a curious and almost inexplicable decision when we are reminded, for example, of the opportunities available to see opera and hear concert music in pre-war London, an artistic environment that appears in stark contrast to the prospects that young Irish composers, especially those from rural areas, had in their country.

Fitzgerald skilfully ushers us through Wilson’s early years, providing political, social and musical contexts for numerous aspects of Wilson’s life and ideas, the significance of which might otherwise have been lost on us. Those early years were dominated by the war and Fitzgerald provides a detailed overview of the dangerous missions Wilson undertook as a radio mechanic with the Royal Navy Arctic Convoys. One story related how his ship, HMS Impulsive, under attack from German U-boats, attempted to rescue survivors of an attacked destroyer. Only seventeen from a crew of two hundred were saved, the rest having perished in icy waters. Details such as these are fascinating – especially for those of us who knew Wilson but never suspected that he had to endure such hazardous times.

It was, strangely enough, on the ship where much of Wilson’s interest in music was triggered. He brought many miniature scores with him and, while at port, started performing with fellow crew members who were also musicians. Though things were difficult, one gets the impression that possibilities to hear and play music were there. Additionally, the College at Sea initiative had been established in 1938, and despite trying conditions, Wilson had been able to start composition lessons. Astonishingly he composed much music while at sea and at war. After the war he went to Trinity College of Music, London, studying composition with Alec Rowley (1892–1958), whose Francophile leanings it seems were a lasting influence.

Too many concerts

Wilson’s decision to move to Ireland in the early 1950s with his lifelong partner John Campbell still remains a strange decision. While homosexuality was coming under increasing surveillance by the British authorities, it was by no means accepted in the oppressive and prohibitive environment of 1950s Church-dominated Ireland. Wilson’s own explanation for leaving London, that ‘there were too many concerts, there were too many exhibitions, too many new operas and plays’, which tended to over-stimulate him, seems to lack credibility. While we may never fully understand this move, there is a suggestion in the book that the extraordinary success that Benjamin Britten enjoyed in post-war English musical society, which established him as the national composer, had some impact on the decision. While the Dublin outback might have appeared an attractive compromise in the early years, the subsequent hardship it brought upon Wilson must have given him pause for thought.

As Fitzgerald highlights, it is Wilson’s tenacity in the face of near constant rejection that impresses. Fitzgerald enriches this story not only with references to Wilson’s private papers and manuscripts (now housed at the Trinity College Manuscript Library in Dublin) and previously recorded interviews, but also from new interviews with fellow associates and friends such as the singer and RTÉ producer Anne Makower, composers John Buckley and Derek Ball and the critic and commentator Ian Fox, among others. By weaving their comments into the book, Fitzgerald tells us as much about the difficult artistic conditions within which Wilson was working in Ireland. The lack of interest shown by Irish opera promoters in the late 1960s and early 1970s and the haphazard nature of productions makes one wonder how anything was achieved. This precarity is highlighted by a section on the opera Twelfth Night (1969). The opera’s second performance at the Abbey Theatre was made possible only because the RTÉ crew filming a variety show that week finished early, enabling the cast to rehearse and perform at reduced cost. On another occasion, Wilson had to provide £2000 of his own money towards a production of his Letters to Theo.

While success in Ireland was difficult, the isolation of being a composer living on the periphery of Europe also comes through, and despite all his efforts to have Twelfth Night performed in London, Scotland, Vienna, Graz and Ontario, the prospect of a little known Ireland-based composer receiving the imprimatur of foreign opera companies was low. Additionally, Wilson’s commendable efforts to find a publisher outside Ireland were met with negative responses. All during the 1970s, the composer was rejected again and again by publishing houses such as Faber, Curwen Edition, Novello, Josep Weinberger Ltd, Chappell and Thames Publishing. He did eventually have some success with Scotus Music Publishing (UK), but this relationship was itself short-lived.

There were other disappointments. An offer to compose music for a 1980 production of Jean Cocteau’s ballet The Wedding on the Eiffel Tower was eventually rejected; music for a play, Scapegoat, by Elsa Gress, never materialized; many other pieces of incidental music that Wilson wrote remained unperformed. These experiences no doubt fed into Wilson’s desire to help build a better infrastructure for music in Ireland, to which his long-term involvement with the Association of Irish Composers, the Dublin Festival of Twentieth-Century Music and the Irish Composers Centre (an incarnation of the AIC during the 1980s) attests.

While the book is structured in a more or less chronological fashion, Fitzgerald cleverly knits together different threads of Wilson’s work in a way that avoids the tedium of standard chronological placement. For example, a discussion about the early song cycle, Carrion Comfort (1966), a setting of a number of sonnets by Gerard Manley Hopkins, and A Woman Young and Old, a setting of Yeats, leads into a more involved outline of Wilson’s ongoing relationship with the poets and his future engagement with their poetry. In other sections of the book, Fitzgerald constantly offers us pointers to consider: a French influence is often referred to even before formal analysis is provided; we are offered valuable references here and there that help us formulate a picture of Wilson’s musical aesthetics and dominant influences.

A Passionate Man

One of the most refreshing aspects of this book is Fitzgerald’s refusal to offer us a hagiography. Indeed, every one of Wilson’s pieces discussed is subjected to the highest levels of scrutiny and assessment. For example, Fitzgerald’s extended analysis of Wilson’s opera from 1995, A Passionate Man, is quite prepared to highlight how the work runs contrary to Wilson’s own stated views on what is required to create a successful dramatic work. While insisting that libretti need to be simple in line and plot, and that they should have story lines that are already well known to audiences, Wilson does not meet these basic prerequisites himself. Fitzgerald’s detailed outlining of the opera exposes a rather unnecessarily prolix libretto, which dangerously detracts from characterization and plot. The additional use of a synthesizer as a replacement for brass and other instruments is highlighted as a compromise that should not have been attempted. There is in this overview of A Passionate Man a sense that not only had Wilson bitten off more than he could chew but that very fundamental errors were allowed to negatively impact the project. There is something fanciful about the blind optimism that must have continued to feed this project despite the inevitably poor results.

Harsh critiques such as these, however, place into relief Fitzgerald’s more positive assessments like those relating to works such as Angel One, for fourteen solo strings, which is described as ‘a particularly strong composition’, and the Viola Concerto, the third movement of which is ‘a well-argued and convincing musical structure’.

The final chapter of The Life and Music of James Wilson is designed to provide the contexts for assessing Wilson’s work. His compositional achievements are placed against the background of frequently appalling infrastructure and official support, early attitudes that tended to consider him as an amateur, and Wilson’s own predisposition for composing works that were likely to present insurmountable logistical problems. Fitzgerald is not afraid to address some issues that he considers unfair comparisons. While Wilson’s auto-didacticism was often seen as lacking in technical rigour, Fitzgerald is rightly quick to suggest that many of his contemporaries also displayed evidence of uneven technique. A criticism that compares Wilson’s ostensible compositional limitations with an unquestionable identification of Brian Boydell ‘as one of Ireland’s most important composers’ is posited by Fitzgerald as ‘a curious sort of double standard’.

That sort of evenhandedness and a willingness to question sacred cow narratives are the hallmarks of Fitzgerald’s musicological work. The value of The Life and Music of James Wilson is that it offers an eloquent overview of one composer’s contribution to musical life in Ireland and a probing analysis of core works. Thanks to Mark Fitzgerald, another piece of the jigsaw is in place.

Published on 14 July 2015

Benjamin Dwyer is a guitarist and composer and the author of 'Different Voices: Irish Music and Music in Ireland'. He is Professor of Music at Middlesex University's Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries.