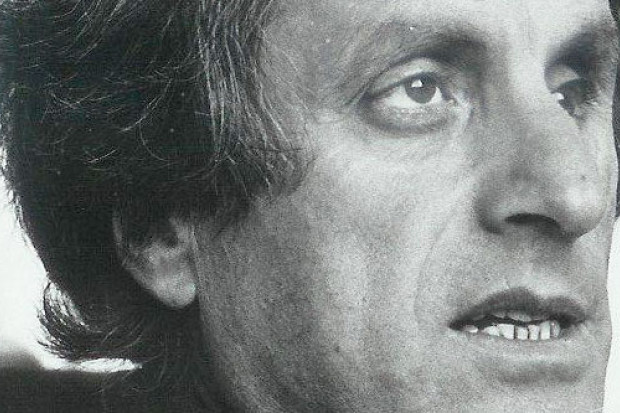

The recording session for Tarik O’Regan’s ‘A Letter of Rights’ at the Chapel of All Hallows, Dublin City University, in 2018. (Photo: Chamber Choir Ireland)

Inspired by a Letter

Chamber Choir Ireland directed by Paul Hillier has recorded a number of discs of contemporary music, notably the RTÉ Lyric FM CD One Day Fine and single discs devoted to Gerald Barry (Orchid Classics) and Tarik O’Regan (Harmonia Mundi). The new disc from Naxos consists of two works focusing on documents.

A Letter of Rights by Tarik O’Regan is a setting of a text by Alice Goodman, currently an Anglican priest, but probably better known to a music audience as the librettist for the first two operas by John Adams. Commissioned by Salisbury Cathedral to mark the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, Goodwin’s text, unsurprisingly for the author of Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer, is a strongly politicised view of the historic charter. She decided to focus on clauses 39 and 40, which concern the right to due legal process (‘We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right’). This is reinforced by the title of the work, which was taken from European Parliament Directive 2012/13/EU of 22 May 2012 on the right to information in criminal proceedings. In an interview with the BBC in 2015, she explained that the work concerns ‘the constant need for our rights to be restated because of things like the present [British] government’s animosity towards the European convention on human rights’. Surrounding this in the collage-like text are references to the historical context and the need to record laws that can curtail the rule of an autocratic king on the one hand, and the physical labour required for the creation of a document in the thirteenth century on the other. As parchment is derived from the skins of animals, the first thing that must occur is a death, the slaughter of the sheep. The reference to sheep in conjunction with sacrifice has of course strong religious connotations, but the reference to the ‘bloodshed behind the ink. Behind the Charter of Liberties’ seems to allude to the violent suppression of rights in various parts of the world as well as the bloodshed that occurs in attempts to secure rights.

The eight sections of the text form a loose structural palindrome and O’Regan highlights this in his setting by recycling the musical ideas used in the first four sections in reverse order in the second half of the piece. Tellingly he states that he was drawn to ‘the idea of poise’ in Goodman’s libretto explaining that this relates to both the way in which parchment was created and also ‘the delicate nature of arriving at the wording’ that was placed upon the prepared skin. It would seem that for O’Regan the process of creating the object was more important than the political content of the document. He therefore decided to give the music a ritualistic feel, something that is emphasised not just by the recurring text, but also by the opening string material with tolling bell which recurs at the close of the work.

What one actually thinks of the music will very much depend on your taste. It is written in a relatively straightforward extended tonal language, indebted to minimalism, while some of the choral writing (like the opening ‘Parchment, no vellum’) sounds quite reminiscent of Britten. The overall pace of the work is slow. While the surface gives the impression of gathering speed at a number of points such as the opening of the second section, which introduces a repeated-note string semiquaver idea, or in the fifth section where there is the conjunction of semiquavers with loud bass drum patterns, the underlying harmonic pulse feels fairly slow throughout. The piece is tautly constructed and the choral parts in particular are well written and probably very satisfying to sing, but for this listener the composition seemed a somewhat pallid response to what is potentially a very potent text. None of the musical ideas seemed particularly striking or memorable. One came away instead with a generalised impression of mood. On the other hand, there is a strong market for the type of pleasant sounding if bland choral music that leaves one tempted to loosely paraphrase Thomas Beecham and say it is ideal for the audience that doesn’t particularly like music but loves the noise choral music makes. The performance sounds very committed and the acoustic gives a pleasant roundedness to the choral sound while the detail of the orchestral parts is caught well even in the passages that are dominated by the bass drum.

Triptych

The contrast with the second work on the disc, Triptych by David Fennessy, could hardly be greater. The first piece Letter to Michael was premiered by Chamber Choir Ireland in 2014 at the Cork Choral Festival, and made such an impression on Paul Hillier that he decided to ask Fennessey for two further pieces, which now form the second and third sections of Triptych, namely Ne Reminiscaris and Hashima Refrain. The first piece, a visceral assault on the listener, was inspired by a letter written in 1909 by Emma Hauck, a patient in a Heidelberg psychiatric hospital, which is reproduced on the back of the CD booklet. The almost illegible page consists of hundreds of iterations of the words ‘Hertzenschatzi Komm’ (sweetheart come), a plea to her husband which it seems was never sent to him. Much of the work consists of a dense 16-part texture, which thins out at the close, where tender reiterations of Hauck’s plea in solo voices give the work an unexpected poignancy.

Fennessy is a composer who is not afraid to take risks and the second piece begins with a substantial quotation from the Penitential Psalm Domine ne in furore tuo by Orlande de Lassus, setting the words ‘Miserere mei Domine’. The approach to the cadence is then isolated and repeated by one group from the choir while over this is layered a series of solo voices setting an English text which Fennessy describes as suggesting an awakening from a coma or deep sleep. After reaching a climax, it seems we are to return to the Lassus, now somewhat blurred textually and musically, to conclude the piece. Unexpectedly, as the Lassus reaches a cadence, a series of descending solo voices intone the word ‘patience’ which makes the work seem to break out from the frame that had been created by the beautiful constraint of the Lassus. The third work sets two Japanese texts, one piece of graffiti from 2010 and the other a tenth-century text, both of which look back to the past. This is perhaps the least immediate of the three works, but the fragmented opening gestures, interleaved with references back to Letter to Michael, coalesce into a more homophonic texture before the gentle haunting ending of the work.

Taken together the three Fennessy pieces form a powerful and enthralling experience. As with the O’Regan work, the piece receives a strongly committed performance from Chamber Choir Ireland which negotiates the wide emotional range from explosive to quietly restrained with aplomb. It is possible the disc will appeal to two quite different audiences. For those looking for a pleasant wash of choral sound that skilfully blends minimalism with elements of the English choral tradition the O’Regan will appeal, while for those interested in a highly individual exploration of the possibilities choral music offer and an intensely gipping engagement with intense psychological states, the Fennessy is a must.

To purchase Letters, visit: www.chamberchoirireland.com/recordings/letters/

Published on 20 January 2021

Mark Fitzgerald is a Senior Lecturer at TU Dublin Conservatoire.