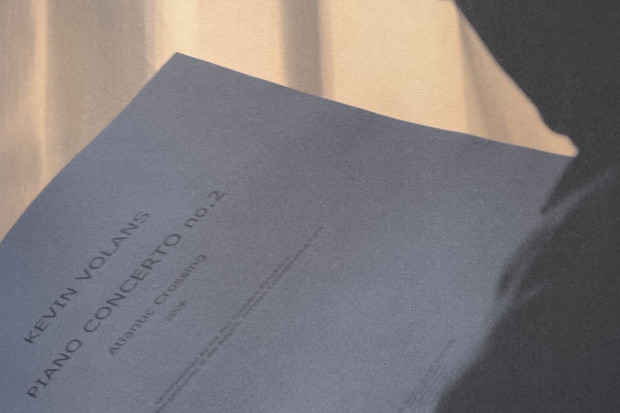

Claudia Boyle and Clare Presland in Alice's Adventures Under Ground (Photo: Padraig Grant)

Imagination Runs Wild

Among those present at the Irish concert premiere of Gerald Barry’s Alice’s Adventures Under Ground back in March 2017, the consensus seemed to be that this was an opera that could not be staged. Yet the version that premiered at the Royal Opera House in February 2020, in a co-production between the ROH and Irish National Opera, somehow managed to surmount the logistical challenges of near constant scene and costume changes. This new film of Barry’s opera, released online on 5 November, is based on that original production with Hugh O’Conor directing the camera work to commit Barry’s opera to the screen. Audiences have the chance to access the work via Irish National Opera’s website until 4 December.

Alice’s Adventures Under Ground is essentially a 50-minute whirlwind tour of the Alice books, racing through many of the more famous episodes whilst also leaving out a great deal. Indeed anyone not familiar with the Alice books before listening to the opera would be quite perplexed at the way in which scenes tumble into each other without any logical connection. Rather than attempting to impose some kind of order or coherent narrative on this, director Antony McDonald simply runs with it, matching every gesture of Barry’s music to a gesticulating limb of the assembled cast.

A Victorian children’s fold-out picture book provides the frame, and – as with Barry’s The Importance of Being Earnest (2011) – it is that peculiar mix of Victorian emotional suppression and cruelty that Barry and McDonald frequently seize upon to comic effect. Whether it is the Duchess’s council to beat a child when he sneezes or the Queen’s obsession with beheading, the regimented excesses of Victorian society – already implied in Carroll’s books – are made explicit in the Barry opera. When they are not singing one of Barry’s careering vocal lines, the characters’ spoken interactions are frequently in the form of strident declamations if not all-out shouting. While this comes across as very amusing most of the time, it has a dark edge that doesn’t quite chime in with the Royal Opera House’s marketing of the original production as an ideal treat for all the family.

That said, there is also plenty of charm and wit. The costumes for the incredibly wide cast (there are 53 roles shared by 7 singers) are ceaselessly inventive and all the more impressive given the rapid changes required. After Alice tumbles into the wonderland, she is approached by four blue bottles (tenor Gavan Ring, tenor Peter Tantsits, bass-baritone Stephen Richardson, bass Alan Ewing) singing ‘Drink me’ which, several second later, transform into four cakes urging her to ‘Eat me’ in a jubilant chorus. Later on, the same four male singers also play choruses of babies, daisies and train passengers in addition to their individual solo roles. In fact, the only singer who doesn’t have multiple roles is soprano Claudia Boyle who plays Alice herself and does a spectacular job navigating the stratospheric heights of the vocal line. Also exemplary in this respect is mezzo-soprano Clare Presland, particularly as the Duchess, while contralto Hilary Summers playing the White Queen amongst other roles continues to prove that she is one of the most distinctive contraltos in the world.

For those already familiar with the concert version, one of the intriguing questions was how the staged production would interpret some of the more wacky episodes in which Barry himself goes off-script. For instance, there is the famous croquet game in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where the sticks are flamencos and the balls are hedgehogs. In Barry’s version this is replaced by an equally bizarre game in which all seven singers furiously declaim random pedagogical instructions taken from piano exercise books in French, German and English. This is realised by having the whole cast rush from side to side at the front of the stage, in front of a portrait of what looks like Chopin while a demented, mute character with an axe hovers threateningly behind.

Although it perhaps lacks the edginess of a live performance, the film allows more insight into the mechanics of the production. The camera angles utilised by O’Conor track the action closely with a range of close-up and rolling shots ensuring that one gets a real sense of the great lengths of detail that McDonald and his team put into every aspect of the production.

By any standards, both the original staging and the film are wonderful achievements in themselves and it is hard to conceive of a better staging of Barry’s opera than this. At 50 minutes, however, the length is just about right. The constant dose of wild antics does have a limited lifespan and tends to stay on the one level making it difficult to conceive of a longer opera. Also, as good as the film turned out to be, I still seem to recall being more amused by the concert versions that I heard at the Barbican and the NCH when the work received its UK and Irish premieres. Without any staging, the visualisation of Alice’s Adventures Under Ground is left entirely up to the imagination of the listener and, in this form, it perhaps aligns more with the great achievement of Carroll’s books which was to let the imagination of the reader run wild. Nevertheless, this film is an important document of a unique production that remains the best operatic treatment of the Alice story.

To view Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, visit this link. The album of the opera is also now available from Signum Classics. For more, visit www.irishnationalopera.ie.

Published on 10 November 2021

Adrian Smith is Lecturer in Musicology at TU Dublin Conservatoire.