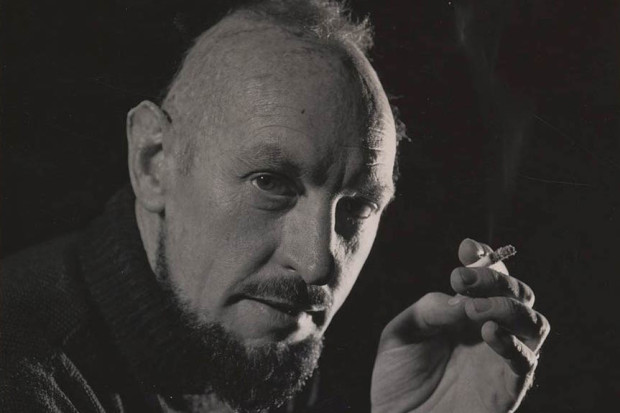

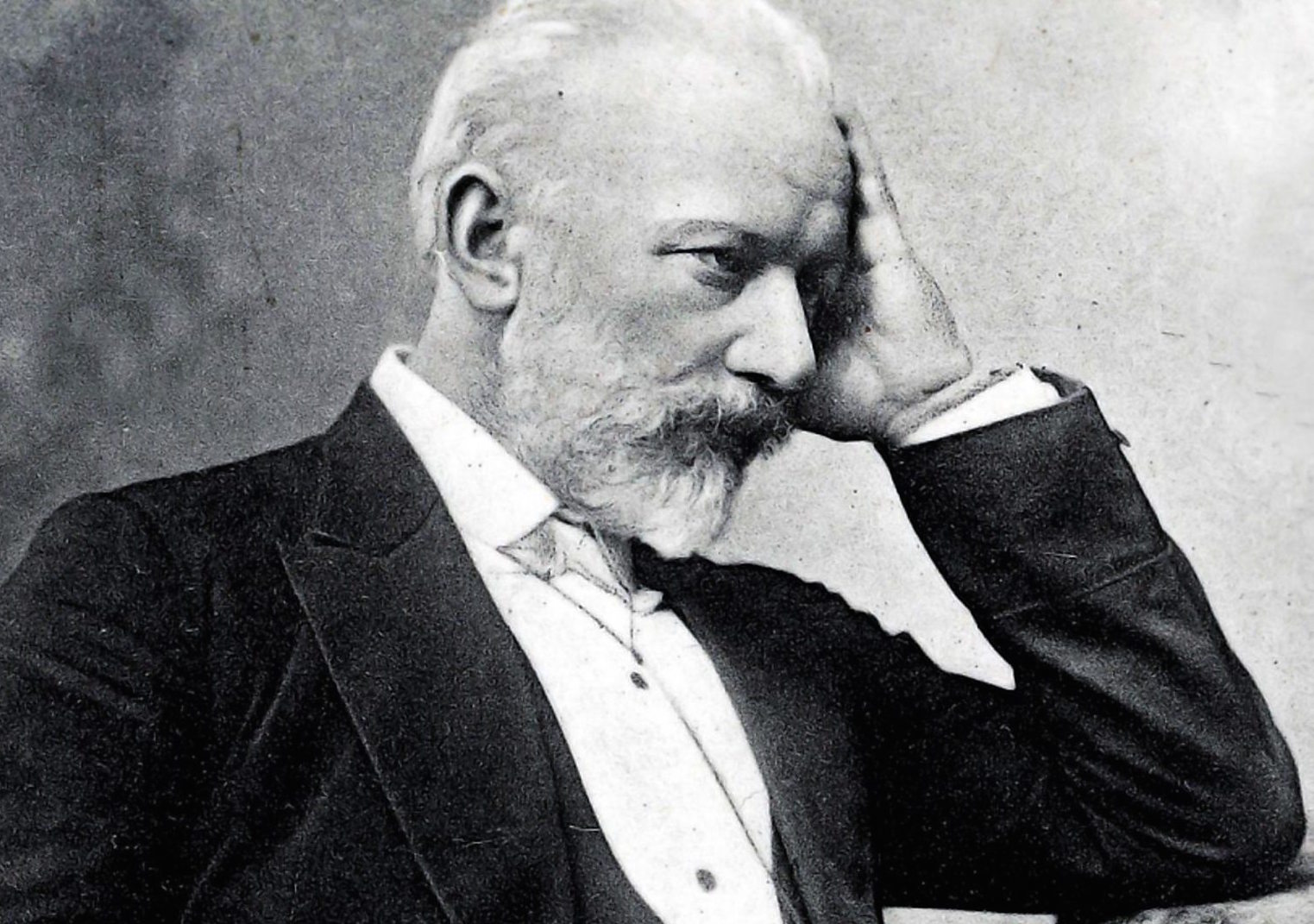

‘Tune-filled genius’ Tchaikovsky

How Not to Market Classical Music

Despite well-intentioned efforts to popularise classical music over the last few decades, there’s no doubt that amongst certain sectors of the media, it still has a bit of an image problem. On the rare occasions that it finds itself under the national media spotlight, it tends to come under attack from all sides for its supposed elitism. During the debate on the fate of the orchestras this time last year, populist radio host Ivan Yates put it quite succinctly when he declared ‘it’s only for snobs anyway, this classical music…’ But even so-called ‘liberal’ commentators like Una Mullally are not above taking swipes at the ‘slabs of music’ regularly being served up in the National Concert Hall that ‘everyone has heard a million times before’.

All too frequently, classical music finds itself categorised as a pursuit for well-heeled elitist types; an accoutrement to a supposedly ‘sophisticated’, ‘cultured’ lifestyle along with fine dining and a knowledge of French wines. In reality of course, a night out at Mrs Brown’s Boys D’Musical? in the 3Arena will set you back almost twice as much as Irish National Opera’s staging of Verdi’s Aida next week at the Bord Gáis Energy Theatre. Nevertheless the myth of classical music’s exclusivity still persists and arts organisations continually face an up-hill battle to project a counter-image of inclusivity and accessibility.

Re-orientating sophistication

For many years now, the default marketing strategy for classical music has been not to do away entirely with the ‘sophistication’ factor but rather to re-orientate it, honing in on the music’s ‘profundity’ and ‘revelatory power’, its ‘insight into the human condition’, its capacity to bring us on an ‘emotional journey’ and several other familiar clichés. Riccardo Muti’s introduction to this season’s brochure of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra is fairly typical in this respect:

Music is a necessity of the spirit. Better than the economy, politics or verbal languages, music provides direct communication to the soul. It acts as a balm that allows us to remember, to heal and, ultimately, to grow. […] Through our performances, we seek to embody our society’s highest ideals and foster a desire for a better understanding of our world.

While this might sound slightly fanciful, there is nevertheless a commendable idea behind the sentiments expressed. The message is that this is art for everybody and that you don’t necessarily need to be a connoisseur or an expert to get something from the music – you just need to be a citizen and a human being.

Whimsical and quirky

In this social media age, however, such lofty ideals have started to come across as slightly staid and a new strain of marketing has recently emerged that attempts to inject some life into the dusty classics with a dose of folksy, nudging humour mixed with a sense of unbridled enthusiasm. Here is the promotional blurb for tonight’s concert with Vasily Petrenko and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic who are playing Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition:

Fancy a night at the pictures? Mussorgsky’s seen things you wouldn’t believe: talking skulls, dancing chickens, ancient castles and a witch who lives in a hut with hen’s legs. They all come singing and dancing to life in Pictures at an Exhibition: pure fairytale magic, drenched in spectacular orchestral colours.

I think most people will agree that this is fairly cringe-worthy stuff where the whimsical and the quirky are forced to perform cartwheels alongside each other in the service of making Mussorgsky’s piece sound more like a children’s Halloween pantomime than an orchestral concert. Encouraging more people to come to classical concerts is perhaps not best achieved by addressing them at the level of a five-year-old.

Cliché-ridden hysteria

As bad as the Liverpool Philharmonic’s efforts are, they make for comparatively academic reading when judged alongside the marketing efforts of our own RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra which read as if Vogue Williams had just been installed as principal conductor. Instead of a brief paragraph enthusiastically promoting the music we are greeted by an out-of-control torrent of cliché-ridden hysteria. Here is the description of this Friday night’s concert of music by Tchaikovsky on RTÉ’s website:

Romance is in the air! And from Russia with love comes an evening of heart-on-sleeve emotions courtesy of the tune-filled genius of Tchaikovsky. Dancing shoes at the ready (although you’ll have to settle for some vigorous foot-tapping) with the bright, buoyant elegance of the Polonaise from Eugene Onegin. And if you prefer your opera bite-sized and brimming with melody, then the Overture from Pique Dame – a cautionary tale for all you Lotto-addicts out there of gambling with cards and love – are [sic] just up your street. Proof that music critics really can get it wrong, we have a violin concerto described at its premiere by one as ‘stinking music’. #fakenews and we think it smells sweet enough to fall in love with.

Proof indeed. But seriously, what kind of music (classical or otherwise) deserves to have this ridiculousness foisted upon it? Certainly not Tchaikovsky who has his own problems. All too often he’s written off solely as a composer of hit-tune melodies, a caricature that the above paragraph goes out of its way to reinforce.

And this excerpt by no means constitutes the outer limits of RTÉ’s latest promotional zeal. For instance, Nathalie Stutzmann’s concert on 11 January that will open with Haydn’s Symphony No. 94 in G Major – better known as ‘The Surprise’ symphony – is introduced as follows:

Boo! Enjoy surprises? Feel a bit short-changed by how few jokes there are in classical music? Then you’ve got a treat in store with Haydn’s 94th Symphony […] Fizzing with colour and vitality, it’s a work of meringue-liked delicacy – crunchy on the outside, soft and gooey inside – and every bit as tasty.

Following this ‘treat’, you can then ‘work off the calories’ with Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 1 which follows in much the same vein:

His First Piano Concerto is a boisterous affair altogether, the orchestra as busy as bees happily making honey until the piano, intent on mischief, makes its presence felt. A delightful chase between the two around the sunniest of gardens follows. Or at least that’s what it sounds like to us.

If these aren’t excruciating enough, perhaps the highlight of the season is this concert of American-themed music with works by Copland, Williams and Puccini scheduled for February:

Yee haw! Stetsons, spurs and six-shooters at the ready as we thunder into the Wild West for an evening of bronco-busting buckaroo bravado, and love and desire during the Gold Rush. Heck, we’ll even throw in a tour of the Grand Canyon! American Sarah Hicks […] takes the reins of the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra for a rip-roaring, hold-on-to-your-saddles celebration of cowboys and cowgals.

Who is the intended audience for this? Clearly not the regular punters, most of whom, I imagine, would spit out their Prosecco in horror at being patronised by such twaddle.

Audiences need to be respected

No arts body that respects their audience would address them in such a condescending fashion. Would the Abbey Theatre have marketed Druid’s production of Richard III last month as an evening where ‘everybody’s favourite villainous king returns for an orgy of blood–spattered shenanigans with several hilarious twists that’ll have you just “dying” (like most of the cast) with laughter!’? Not if they wanted to be taken remotely seriously.

Classical music is not so impenetrable that it requires this type of nonsense. Audiences need to be respected if classical music is to succeed in carving out a viable future for itself. Moreover, promoters need to develop a certain level of faith that audiences have the capacity to make informed decisions by themselves rather than trivialising the music to this absurd degree, a strategy which is more likely to turn prospective punters off.

Despite this, I’ll be there on Friday to hear the work of the ‘tune-filled genius’ from Russia although, on this occasion, I think I’ll probably resist the temptation to purchase a programme out of fear of what might be lurking inside.

Published on 22 November 2018

Adrian Smith is Lecturer in Musicology at TU Dublin Conservatoire.