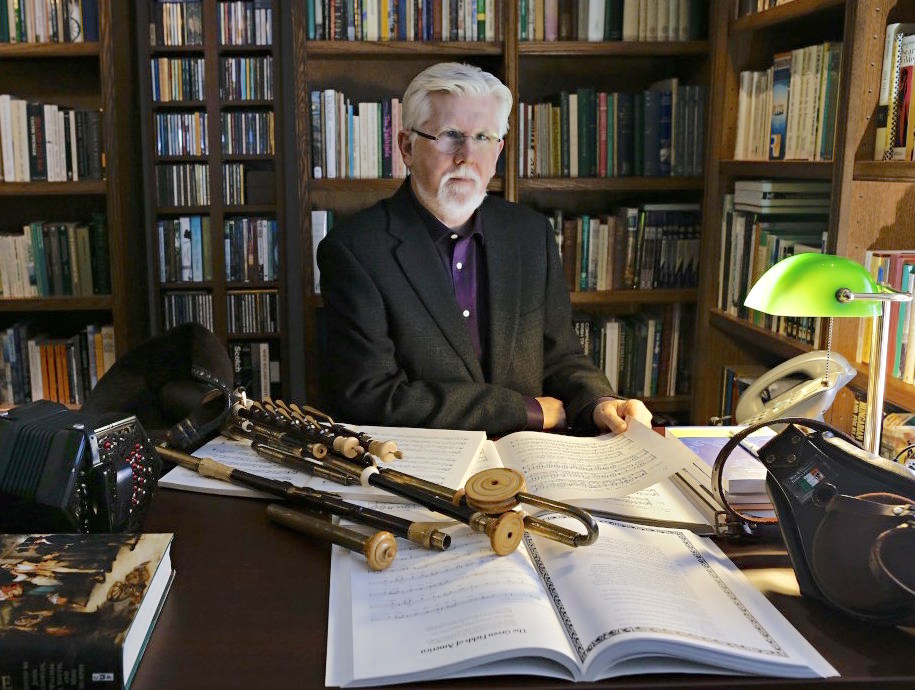

Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin (Image: Alain Decarie)

A Guide to a Global, Hybrid Music

One year shy of the twentieth anniversary of its publication, the reissue of Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin’s Irish Traditional Music book comes in a productive period for the author who, in 2016, published the weighty Flowing Tides: History and Memory in an Irish Soundscape (Oxford University Press). The latter is the culmination of a long career as an academic active in a number of institutions in North America, most recently as the bilingual Johnson Chair in Quebec and Canadian Irish Studies at Concordia University in Montreal.

The 2017 edition, A Short History of Irish Traditional Music (O’Brien Press) is, at first glance, a book for a different audience, one not necessarily interested in expansive footnotes, extensive reference lists, or detailed arguments about sound and identity politics.

Pocket histories

When it was originally published in 1998 as A Pocket History of Irish Traditional Music, there was a couple of other similar books on the market, most notably Ciaran Carson’s 1986 Irish Traditional Music (Appletree Pocket Guides). Both authors shared in common strong profiles as traditional musicians and as writers and researchers in the area of Irish music culture. Their respective books covered many of the same topics, most notably a section on session etiquette. It is, perhaps, that section, more than any other, that hints at the original intended audience; the interested if untutored, seeking an overview of the tradition in terms of sounds, styles, culture and context. This group would probably have included people resident in Ireland, though not necessarily directly engaged with the tradition; cultural tourists to the island eager for a simple introduction; and interested parties in the Irish diaspora and beyond, keen to learn more about this vibrant music culture.

Ó hAllmhuráin’s book proved distinct from Carson’s (very fine) book on two levels; first it provided a more clearly defined historical arc in its structure, and second, crucially, it included a section devoted to the place of Irish music in the diaspora, most notably in North America. While this would hardly seem radical today, previous books on Irish music, including Tomas Ó Canainn’s Music in Ireland (1978; reissued in 1996 and 2005), and even Breandan Breathnach’s Folk Music and Dances of Ireland (1977), did not acknowledge the music-making going on outside of Ireland which had a huge impact on the tradition ‘at home’.

Medieval to new millennium

When comparing the old edition to the new, interestingly there is not much new material evident (ostensibly). The book maintains easy movement between discussions of sounds, styles, instruments, voices and key protagonists from start to finish. The original ten chapters are reproduced in the 2017 edition, moving from music in early and medieval Ireland right through to the new millennium. In between, there are concise, accessible chapters on music during the Tudor and Stuart period and on the emergence of the dancing masters in the context of the Penal Era, for example.

Two sets of ‘exiles’ are accounted for, those of 1700-1830 (including the Scots Irish in Newfoundland, and those shipped to Australia) and migrants of the Irish famine and post-famine era from the 1840s onward. The impact of media is assessed in a chapter that ruminates on the role of recording technology and radio, as well as the musical changes brought about in the dance halls. The institutionalisation of Irish music, particularly through the work of Séamus Ennis and the Irish music grass-roots organisation, Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, is discussed, as is the role of Irish composer Seán Ó Riada, whose Irish traditional music ensemble work had a considerable impact on group playing in the tradition.

Women to the fore

As one might expect, it is the final chapter that contains substantially new material (in contrast to the introduction which features a new initial paragraph but retains its original structure and content, for the most part). In the closing chapter, the section entitled ‘Women to the Fore – Finally!’ caught this reader’s eye, not just because it focuses on the role of women in the story of Irish music and dance – from breaking the ‘glass ceiling’ in ceilí bands to recording women-only albums – but also because of the way in which these materials are framed.

The author locates these developments within shifting national and international discourses on women’s rights, declining religious influences and growing professional opportunities for women. This section also lists a number of female scholars producing music and research in the area, underscoring not just the opportunities for women but also the growth of Irish music scholarship.

The final section of the chapter, ‘Quo Vadis?’, expands upon this aspect of Irish traditional music, highlighting the expanding presence of Irish (music and dance) studies in Ireland and North America in particular, which the author sees as intersecting with the folk music and dance scholarship in the UK and beyond, as well as being in a healthy exchange with journalists and public intellectuals, while finding particular creative sites of expression through teaching and performance at national and international festivals and summer schools.

Key publications

There are other differences, some which may be less important to non-academics, but, for people who use this book for teaching first-year Irish music and dance studies, prove very useful. The very welcome select bibliography is itself an important overview of key publications on Irish music, song and dance, thereby providing a critical resource for anyone interested in further reading. The new index also makes this edition much more navigable, as a reader can look up an item and be directed to specific points in the book.

There was, perhaps, a missed opportunity in not expanding the ‘Music, Song and Dance Collection’ which maintains its original four entries (there have been many publications in this area in the past twenty years).

The list of traditional music organisations has shrunk from five to three (CEOLAS now being defunct, and Na Píobairí Uilleann left out, for some reason). A welcome addition has been the section on ‘online resources’, though at three entries, it is quite short. Finally, the discography has a few more entries, but on the whole retains the same shape. The suggested recordings remain iconic, though the absence of more recent young Irish bands may leave the younger reader wondering about current commercial recording activities.

Global, hybrid and multifaceted

Perhaps the best way to sum up the ethos of this book is to note that just as the 1998 edition asked us to consider music-making from North America as part of the story of Irish traditional music, this edition asks us to appreciate the global, hybrid and multifaceted nature of Irish music today, as well as its local, intimate iterations and flavours, be that in Cork, Chicago, Canberra, or Chennai.

There are other books in the market that offer more comprehensive introductions to Irish traditional music, including Helen O’Shea’s The Making of Irish Traditional Music (2008), and Sean Williams’ Focus: Irish Traditional Music (2009), both of which are excellent. But when it comes to a compact, accessible, engaging, introductory read, Ó hAllmhuráin’s book stands the test of time and is made all the more durable by the select additions in this updated version.

A Short History of Irish Traditional Music by Gearóid Ó hAllmhuráin is published by O’Brien Press.

Published on 13 September 2017

Aileen Dillane is an ethnomusicologist and musician based in the Irish World Academy, University of Limerick.