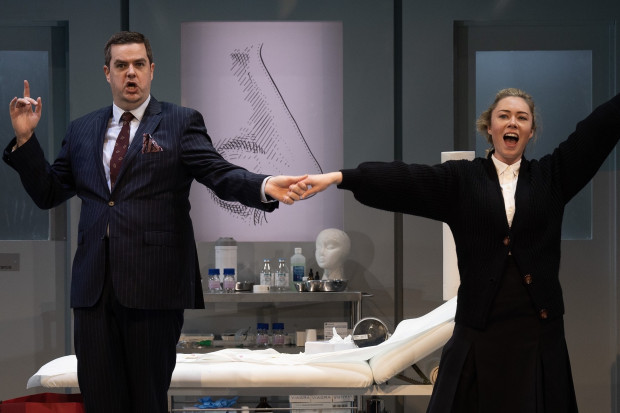

Lauren Kinsella in Ian Wilson’s ‘The Last Siren’ at the Dublin Theatre Festival last year – ‘contemporary Irish composition is marked by a pervasive theatrical aesthetic’.

A Fractured History for Fractured Arts

Altering States: 100 Years of the Arts in Ireland was a nine-part series produced and presented by Clíodhna Ní Anluain, broadcast on RTÉ Radio 1 from July to September last year, and repeated over the past month. It promised ‘a thematic look at how the arts have fared over the last 100 years, and how Irish culture has been reflected in the arts.’ Each episode was topically structured – by venues, education, archives, funding and sponsorship, regional developments, the role of international artists in Ireland, perceptions of Irish culture abroad, and so on.

The series was an ambitious project that dissented from its ostensibly commemorative function by critiquing the state’s fractured engagement with the arts over the last century. For those intending to catch up via RTÉ Player, the treatment of music is inconsistent: it dominates some programmes and is absent from others. Moreover, the musical perspective is valuable but concerned almost exclusively with classical traditions. Popular music is ignored and jazz is barely mentioned apart from the commercial success of the Guinness Cork Jazz Festival. Traditional music fares only slightly better. The activities of contemporary composers receive some attention, although Seóirse Bodley is the only such figure to feature as a contributor. Coverage of the most prominent voices to emerge since the millennium is particularly scant.

Landmark musical projects last year, such as Composing the Island and its partner publication, The Invisible Art: A Century of Music in Ireland, 1916 – 2016, have combed through and chronicled an extensive (but not exhaustive) catalogue of work by Irish composers, past and present. Instead of chiming with or directly challenging this emerging narrative of modern Ireland’s music history, Altering States steered the conversation in another direction. Ní Anluain’s fragmented, non-linear approach to music highlighted how individual labour and infrastructures were crucial to fostering Irish composition and performance. By dint of its multidisciplinary scope, the series underlined the need to reinvigorate the discourse about the relationship between music and the other arts in this country. For all the progress that has been made in recognising the worth of our composers, cultural gatekeepers such as the Royal Irish Academy still denied musical works a place in its 2016 centennial pantheon ‘Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks’, which was a collaboration with the Irish Times.

Musical arts

Let us begin with what Altering States had to say about the Irish musical arts on their own terms. In ‘The Arts and Education’, Ní Anluain inquired about tensions between classical and traditional values. Musicologist Ita Beausang responded that figures such as Ó Riada and Ó Súilleabháin bridged that divide through the stylistic diversity characteristic of their output and university teaching. In ‘Aspects of Irish Arts Abroad’, former director of Culture Ireland and now Director of the Kilkenny Arts Festival Eugene Downes emphasised traditional performance and Riverdance in the state strategy for marketing Irish music internationally.

Altering States limited the musical arts to traditional and classical forms, with classical parameters delineated by conventional concert and operatic repertoires; there was virtually no recognition of electronic music. Anecdotes about the early years of the Radio Éireann National Symphony Orchestra made for entertaining airtime but, disappointingly, ensembles so significant to the music scene in recent decades such as Crash and Concorde were overlooked. In that sense, the ‘Artists from Elsewhere’ episode was a missed opportunity to acknowledge the work of individuals such as the US-born Concorde founder and composer Jane O’Leary. More usefully, musicologist Mark Fitzgerald cast light on composer James Wilson who moved to this country from England in the 1940s and eventually became an Irish citizen. Wilson’s initiative in co-founding a compositional summer school with John Buckley, and his impact on a younger Irish generation, echo a situation described by Beausang in the earlier programme.

For many years, music provision in primary and secondary schools depended substantially on the goodwill of individuals negotiating the constraints of an unsupportive system. By the 1970s, free education and redesigned syllabi had ameliorated the situation: music became more accessible to an expanded student cohort who exploited new opportunities to study it at college.

As noted by the Contemporary Music Centre’s Jonathan Grimes in the subsequent ‘Archiving’ episode, this policy shift had a pronounced effect. The Association of Young Irish Composers (now the AIC) was formed in 1972 and, apart from arranging concerts of new works, the organisation aimed to ‘archive… and collect… to make the music accessible.’ That ethos informs the CMC – which, Grimes commented, is now mined by musicologists producing increasingly visible research into the nation’s composers. A network of creative voices, performers and scholars is evidently engaging with each other more than ever before, but what about dialogue between musicians and curators of other art forms?

Intersections

In treating separately music, theatre, and the visual arts, Altering States failed to capture how much contemporary Irish composition is marked by a pervasive theatrical aesthetic. By way of example I cite the two-day Inappropriate Moments festival of Jennifer Walshe’s work which was staged at the Project Arts Centre last year. Interestingly, Walshe has recently theorised the theatrical turn. In her manifesto ‘The New Discipline’ she describes a practice that:

connect[s] compositions which have a wide range of disparate interests but all share the common concern of being rooted in the physical, theatrical and visual, as well as musical…In performance, these are works in which the ear, the eye and the brain are expected to be active and engaged. Works in which we understand that there are people on stage… they are not ‘music theatre’, they are music. Or from a different perspective, maybe what is at stake is the idea that all music is music theatre.

Walsh elides ‘music theatre’ to ‘music’ – in an Irish context, it is also worth considering how ‘music theatre’ slides into ‘theatre’. Altering States is mostly silent on intersections between art forms but there is a need for a conversation about how the relationship between music, theatre, and the visual arts is conceptualised in this country.

Despite a lack of infrastructural support, opera has thrived as a creative form in recent years, partly due to what might be termed a spirit of inter-artistic collaboration. For example, the visual artist Pauline Bewick originated the concept for Raymond Deane’s opera The Alma Fetish (2013) and created new images for its National Concert Hall performance. Last October, Ian Wilson’s 2014 experimental opera The Last Siren was staged as part of the Dublin Theatre Festival. In the absence of a dedicated contemporary-opera company such as Wilson has called for (most recently in September), the festival’s embrace of opera is a boon. On the other hand, folding opera into a programme of predominantly literary theatre diminishes the genre’s status as a distinctive art form. Dublin Theatre Festival further boasted a ‘uniquely Irish’ production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni in a new libretto translation by Roddy Doyle. Another work which exemplifies, in a different mode, how Irish opera could potentially be construed as extending and diversifying national literary, dramatic traditions is Gerald Barry’s internationally acclaimed setting of Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest (2011).

How theatre constructs itself, as highlighted in the final programme of Altering States (‘Aspects of Irish Arts Abroad’), is therefore relevant to musicians. Theatre Forum director Anna Walsh called for debate about how Irish theatre is ‘presented internationally in the next hundred years’. Her focus on how to project that art form to a global audience models what seems to be a logical future step for Irish contemporary music now that national efforts to consolidate that narrative have started to take shape.

As the lack of score or sound in the Royal Irish Academy canon of artworks attests, the onus also remains on musicians to advocate within the country for contemporary composition and performance as compelling forces of Irish cultural expression. Altering States, notwithstanding its blind spots, can be credited with sparking some reflection on these complex issues.

Published on 9 January 2017

Dr Laura Watson is Associate Professor of Music at Maynooth University.