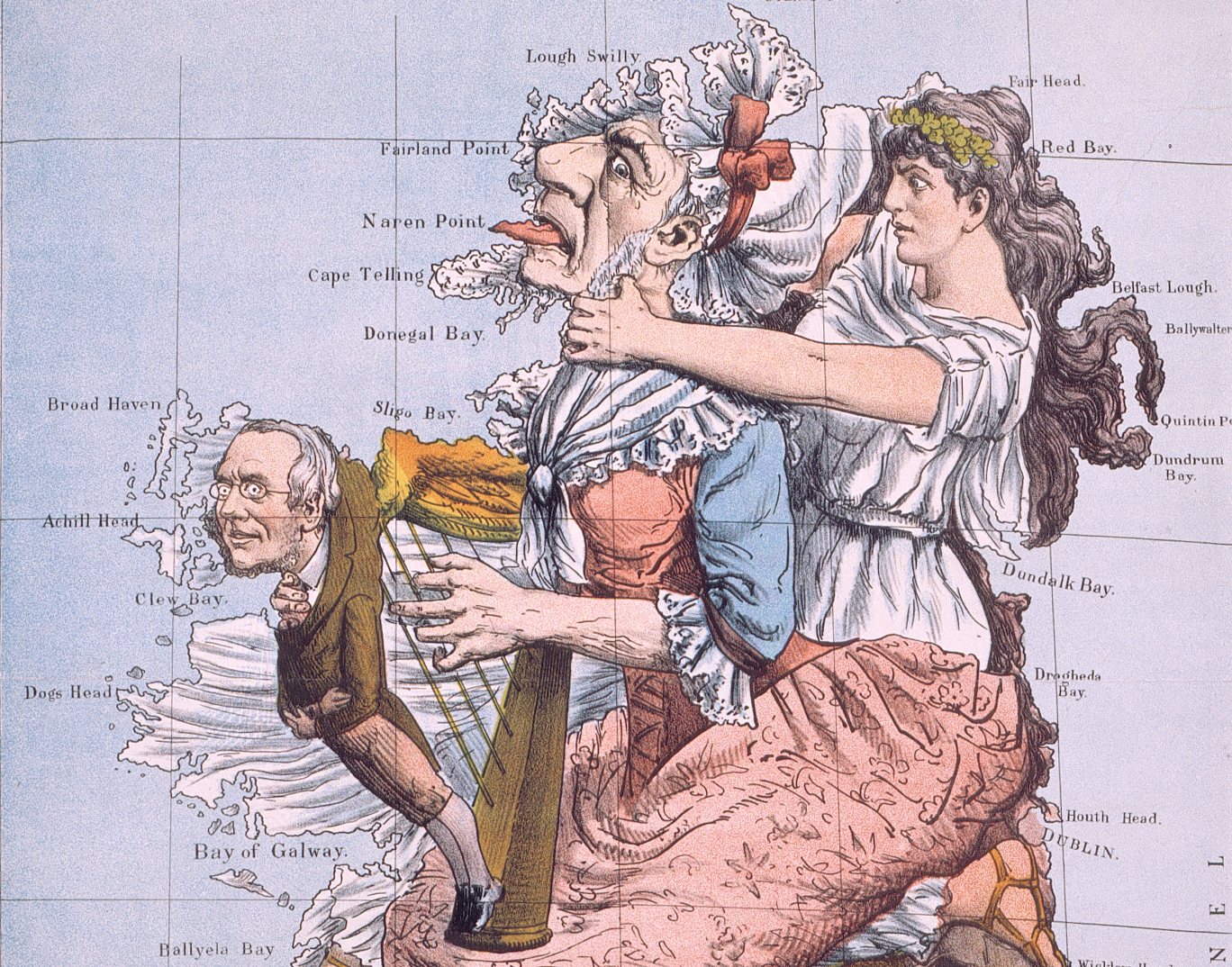

A cartoon from 23 June 1888 – ‘Geography Bewitched: The false Ireland and the true…’. William Gladstone is depicted strumming a harp while being strangled by ‘Erin’. (Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

Exploring Irish Harp Traditions

Harps have been played in Ireland from at least the year 1000, when indigenous performers played an early Irish harp: this is the robust, wire-strung instrument now depicted in the national emblem. From the twelfth to seventeenth centuries, different waves of invaders presumably brought gut-strung medieval and Renaissance harps with them; European pedal harps were played by the affluent Anglo-Irish from the eighteenth century; and, in the early nineteenth century, the Irish harp of the modern era took shape: now a nylon-strung instrument with a pitch-changing lever mechanism on each string to enable key changes. It is this instrument, known variously as lever harp, neo-Irish harp or Celtic harp, which is now most common and which is generally thought of as ‘the Irish harp’. All of the above instruments, however, can be heard in contemporary Ireland, playing a variety of repertoire – early music to contemporary compositions, traditional Irish music, jazz and other genres.

Since harp imagery has been intimately bound up with notions of Irish identity for centuries, and because the instrument is of such symbolical and historical importance, one might also expect a lengthy bibliography of publications in the field. But despite the appearance of relevant articles in periodicals and books, over the last century the number of full-length books dedicated to any aspect of harp history in Ireland appears to be just ten. A recently published and welcome addition is Mary Louise O’Donnell’s Ireland’s Harp: The Shaping of Irish Identity c. 1770-1880 (UCD Press, 2014).

Tuning the harp

‘Tuning the harp’, writes O’Donnell, had a very particular meaning in seventeenth-century Ireland: it became the new English colonial metaphor for controlling the Irish. Harp imagery in relation to Ireland had been in use abroad since the thirteenth century, but it was in 1534, in the reign of Henry VIII, that coins depicting a harp were first minted for Ireland. The instrument was surmounted by the crown of England, with all the political coding that that implied.

In early eighteenth-century newspapers, political pamphlets and other printed materials, however, the harp was now also seen in the hands of allegorical figures such as ‘Hibernia’ and the ‘bard’, imparting home-grown messages that would set political agitation in motion. ‘It is new-strung and shall be heard’ was the optimistic motto of a new political organisation of that period, The Society of United Irishmen. This was a worrying sentiment for the colonists compared with the halcyon days of 1612, when the attorney general for Ireland, Sir John Davies, praised James I’s handling of the country: ‘…The strings of this Irish Harp…are all in tune…and make a good Harmony in this Common-weal. So as we may well conceive a hope, that Ireland…will from henceforth prove a Land of Peace and Concord.’

It is not certain why the harp became the national emblem of Ireland. A musical instrument seems an unlikely choice if a nation has a blank slate and the freedom to choose. But the exquisite timbre of the early Irish harp, and perhaps its virtuosic accompaniment of the performance of highly sophisticated syllabic poetry in the early Gaelic courts, did astonish foreign commentators from the twelfth century. So this pinnacle – and physical embodiment – of Gaelic high art culture perhaps came to define the nation not because it was how the Irish saw themselves but how others saw them.

Harp imagery and harp history

O’Donnell’s new book helps to fill some of the many gaps in Ireland’s published harp history – particularly that of the nineteenth century. She focuses on the importance of the harp in Ireland as a symbol, one whose image helped the Irish to form their national identity. When used as a metaphor, she maintains, it also allowed them to express that emerging nationalism. The author also looks at how patronage of living harpers – and their musical performance – was affected by this use of harp imagery, and she discusses Ireland’s colonial rulers’ symbolic and political uses of harp imagery, from the early medieval period into the seventeenth century and those of indigenous Irish political movements after that. O’Donnell makes her way ably through eighteenth- and nineteenth-century uses of harp imagery in coinage, poetry, literature, religious writings, and political movements to show what directions were followed and where they led, and simultaneously takes us through actual harp history of the period. Musicologists Ita Beausang, Barra Boydell, John Cunningham, and the author herself, have already contributed to modern research in this area. A 2008 PhD thesis by Emily Cullen is the largest single work in the field, but has not led to a published book. So O’Donnell’s new work is significant.

In the first chapter, the author notes the political groupings who used rousing and unifying harp imagery in the lead-up to the 1798 rebellion. These were disaffected Anglo-Irish Protestants; indigenous Irish Catholics, she points out, did not yet use the harp as an emblem. That would appear to have happened later in the nineteenth century after Catholic Emancipation (c.1829), when Daniel O’Connell, for example, used actual harpers and harp imagery to promote his political aims.

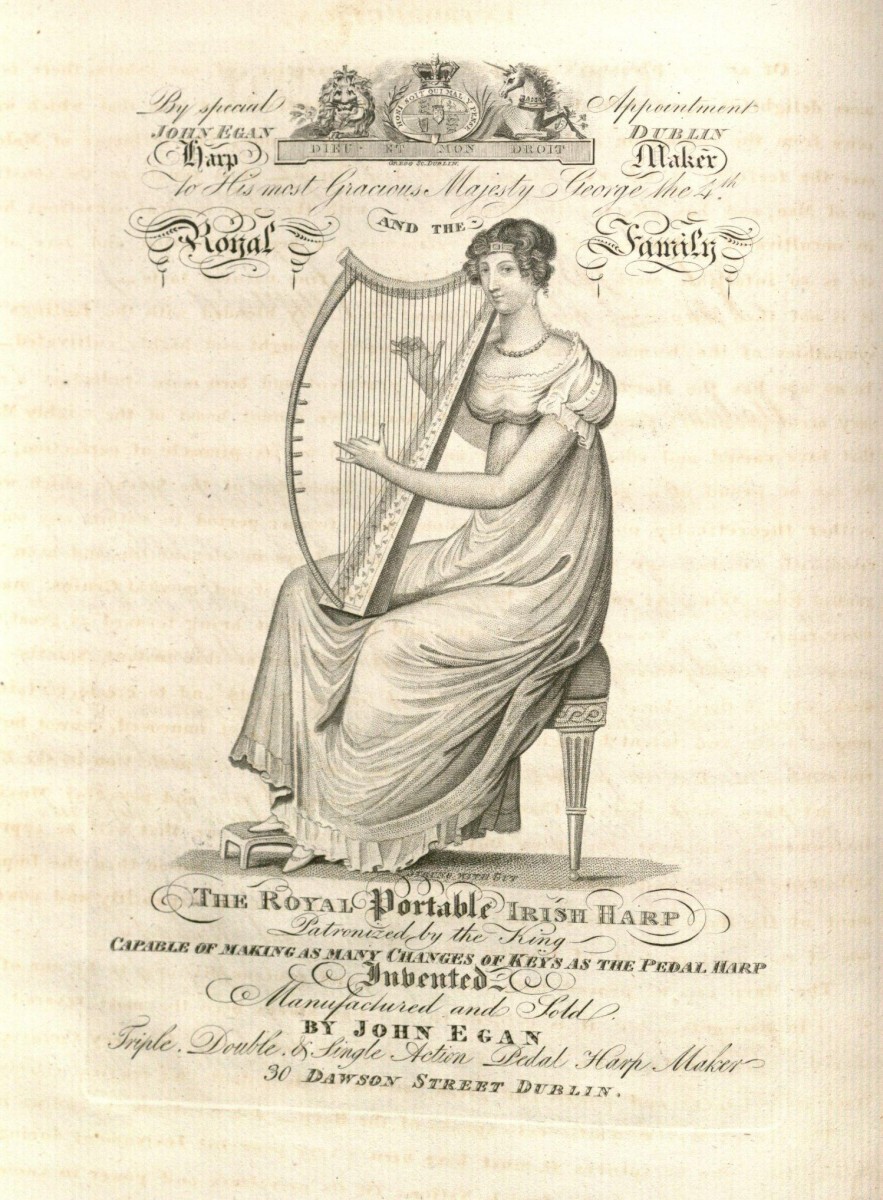

After the disappointment of the 1798 rebellion’s failure, a more pathetic harp was ‘attun’d to sorrow drear’ in the works of Thomas Moore (1779–1852) and others. Chapter three deals with nationalistic harp imagery in the works of the now-eclipsed Irish literary activist, Sydney Owenson (1776?–1859), and the rather more famous Moore. Both authors actually played early nineteenth-century ‘Royal Portable Irish’ harps, built by the talented Dublin pedal-harp builder, John Egan.

The Belfast Harpers’ Meeting

The second chapter – ‘“Towards the Grave of Oblivion”: the Politics of Irish Harping in the Eighteenth Century’ – deals with a pivotal moment in the history of the early Irish harp: the Belfast Harpers’ Meeting of 1792. (In company with almost all modern writers, O’Donnell calls it a ‘festival’; the original organisers talked about ‘assembling’ harpers, and Edward Bunting referred to it as a ‘meeting’, ‘festival’ apparently being used only for religious events at the period.) Without the transcription of the harp music undertaken there by the teenage Bunting – together with the technical, musical and historical information gleaned by him from the mostly elderly harpers who performed – we would have considerably less information about early Irish harpers, their historical playing and string damping techniques, and their tuning and repertoire.

The author subsequently outlines the history of the nineteenth-century early Irish harp revival societies in Belfast, Dublin and Drogheda. Formed in the wake of the harpers’ assembly, O’Donnell tells us of their ethos, activities and students, some of whom were still performing at the end of that century.

A negative narrative

A central tenet of O’Donnell’s argument in her book, presented in chapter two, is that of taking issue with the prevailing mindset, then and now, that the early Irish harp was dying out in the eighteenth century. She reiterates her view that it was rather ‘the idea of a moribund harp tradition’ [my italics] and a ‘negative narrative’ that was established.

Certainly, the mid-century tour of one of the best known of the eighteenth-century travelling harpers, Arthur O’Neill, led him to encounter fourteen harpers in Cavan, for example. But the northern counties did have a much stronger tradition of harping in the eighteenth century than the south. References to harpers in the southern half of Ireland, in the latter part of the century, were already very thin. When speaking of the small number of performers at the second Granard Harp Ball in 1782, O’Neill points out that ‘the decay of the harp at this time appears strongly from the fact, that, notwithstanding the celebrity of the first meeting, two new candidates were all that presented themselves in addition to those already enumerated.’ This brought the total number up to only nine, from seven the year before.

And though news of the Belfast Harpers’ Meeting of 1792 had made it as far as County Kerry in the south west and possibly also abroad (one attendee was Welsh), no harper from south of County Meath attended. The fact that there were so few performers in Granard and Belfast less than forty years after O’Neill’s mid-century tour does also rather imply a steep decline. Bunting himself – the man on the ground – later wrote: ‘[t]en harpers only responded to this call, a sufficient proof of the declining of the art…’. Bunting also noted that by the time of his second publication in 1809 only two of the ten who played in Belfast in 1792 were still alive and that ‘the Belfast meeting was in fact the expiring flicker of the lamp’. He notes further that the second Belfast Harp Society, founded in 1819, ‘discovered no harpers in Ireland, save those who derived their education from Arthur O’Neill, master in the first school’. So, at that point, early Irish harp culture would indeed appear to be hanging by a thread.

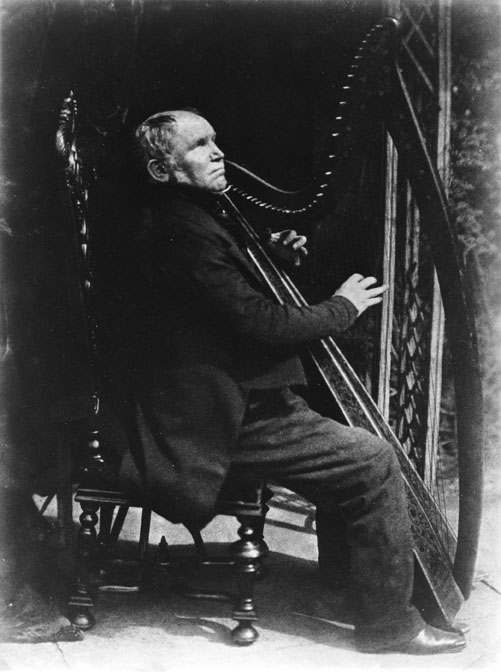

Chapter six follows the carefully choreographed visit to Ireland by King George IV in 1821 and the music performances given in his honour by early Irish harpers. The author also relates Daniel O’Connell’s many public uses of the harp and harpers in his work in the 1840s to have the Act of Union repealed. She follows this with an account of the travels of harp society students Matthew Wall – who emigrated to the USA via Canada – and Patrick Byrne, the only early Irish harper ever to be photographed, in 1845. The odd performer on early Irish harp was still alive around 1900 but it is a pedal harpist of that era, Owen Lloyd, who reinvented himself to become the first period instrument performer on this harp.

Patrick Byrne, 1845

Mary Louise O’Donnell’s perspective throughout her book provides thought-provoking issues to reflect upon and evaluate. I will concentrate here on questions of organology (the physical characteristics of the harps of the period in question), nomenclature and performance practice.

A singular Irish harp tradition?

O’Donnell presents harp history in Ireland as a singularity: ‘the Irish harp tradition’ (my italics). Of the different strands of harp activity she discusses, she writes of all but one as part of a continuity. Similarly, she uses the term ‘the Irish harp’ when describing several distinct instruments. This is a familiar and, to me, problematic concept: an assumed continuum of performers and ‘developing’ instruments from earliest times to modern.

By the second decade of the nineteenth century, as the author herself tells us in chapter five, there were no fewer than six different types of harp in Ireland, without counting visits by Welsh triple-harp players. In addition to the European single- and double-action pedal harps of the salon, there was now a new triple-action pedal harp, invented in 1817 by the tireless John Egan. Pedals change the pitch of all strings of the same name simultaneously, e.g. all ‘C’ strings. (Single-action harps could change the pitch of each string by one semitone, double-action instruments by two semitones and Egan’s extraordinary triple-action harp by three, allowing the performer on such an instrument to play in every major and minor key imaginable.)

Three other instruments also existed: the old wire-strung Irish harp; Egan’s newly invented gut-strung Portable Irish harp (the author points out that there were, in fact, four varieties of these); and his hybrid wire-strung ‘Society’ instruments built for the harp societies trying to keep the early Irish harp tradition alive at this period. The author often doesn’t differentiate between the three, regularly referring to the newer ones also as simply ‘Irish harp’. This leads to some ambiguity and possible confusion when she discusses the period post-1810. Though O’Donnell clearly points out the differences between Egan’s Society harps and his Portable harps, she nonetheless has a tendency to put them in one basket after that, e.g. when she writes of the ‘tone quality and workmanship of Egan’s harps (pedal and Irish)…’ even though the timbre of his two ‘Irish’ harps must have been completely dissimilar.

The early Irish harp was wire-strung, played on the left shoulder, with the left-hand on the treble strings and the right-hand on the bass strings. It had two unison G strings below middle C, and a short octave at the bottom. O’Donnell explains that Egan’s Society harps still shared many of these features. The new Portable harp, by contrast, gave a nod to the early Irish harp in the form of a more curvy shape than a pedal harp, but was strung in gut, played on the right shoulder, had equidistantly spaced strings, and was a technologically advanced instrument with a newly invented mechanism to replace the pedals of its bigger sister. This latter feature enabled the player to remain in the European world of major and minor keys, transposition and accidentals, distinct from the modality of Irish music.

Despite these clear differences, and O’Donnell’s mention in her introduction that Egan’s Royal Portable – ‘Royal’ was added in 1821, when Egan became harp maker to George IV – was the beginning of a new tradition that had ‘little in common’ with the older tradition, she nonetheless afterwards carries on positing a single ‘Irish harp’ continuum across the centuries and situates Egan’s harps within that: ‘Irish harp makers in the nineteenth century carried on the practice of innovation in Irish harp design’.

I would suggest rather that the organic changes in early Irish harp design of the preceding centuries – the slowly increasing size of the instrument; the addition of more bass strings; the lengthening of those strings and the corresponding lengthening of the front pillar – did not lead, at the end of the eighteenth century, to an instrument that was radically different from the medieval period in anything but size, or to one that would have been unfamiliar or unplayable by an early Irish harper of any century. At the end of a perhaps millennium-long tradition, the timbre of the later surviving instruments was still broadly similar to the late medieval harps, as, for the most part, was the medieval technology used in their construction. Nor did its playing technique appear to have changed radically: the later part of the early Irish harp’s history saw players striking with fingertips rather than fingernails but that does not imply any significant change in hand position or technique.

A radical new departure

I see Egan’s Portable Irish harp of the 1810s, by contrast, as a radical new departure. Since it is the ancestor of the modern Irish harp, it deserves particular attention. One might look at what credentials the newly devised harp had to be considered Irish at this stage, beyond Egan’s marketing of it as such, and the fact that it was invented and built in Dublin. The instrument did, in fact, lead indirectly to distinctive Irish harps and indigenous Irish harp performance traditions in the later twentieth century, spearheaded by the fresh approaches of musicians such as Máire Ní Chathasaigh and Janet Harbison.

But Egan’s 1819 advertising of his Portable harp as ‘Irish’ – presumably to attract patriotic clientele – cannot hide the fact that it had nothing in common with the extant Irish harp of the period. It was a game-changer – the invention of a new instrument: a miniaturized single-action pedal harp, minus pedals. O’Donnell describes it as ‘influenced by the design…of the European pedal harp.’ But it was more than that: it was an innovation wholly from within the European pedal harp world itself.

Unlike the sturdy sound box of the early Irish harp – usually carved from one piece of wood – the new harp had a thin soundboard glued to a curved soundbox. The quick decay of its gut strings contrasted with the volume and long resonance of the older harp’s brass wire strings. It had a string pitch-changing mechanism and was tuned in the single-action pedal harp’s E-flat major tuning, in contrast to the early Irish harp’s modal tunings. It was played with a ‘thumbs up / fingers down’ pedal-harp technique rather than an earlier historical ‘hold the ice-cream cone’ hand position. To speak of a continuum in Irish harping, therefore, is to ignore these important discrepancies between the two instruments.

The naming of objects is hugely important to our perception of them. The author’s transplanting of the name of the older harp directly onto the new (‘Irish harp’) makes it more difficult for the reader to differentiate between the instruments and to appreciate the gulf between the two, and perpetuates a spurious idea of continuity of tradition. When describing some of the technical features of the new Royal Portable, for example, she writes of Egan’s ‘modifications to the Irish harp’ [my italics]. I would also question the use of the word ‘modification’, which has an implication of change made to something that already exists. And when noting a further innovation Egan made to the Royal Portable, the author asserts that ‘[f]or the first time in its history, the Irish harp was capable of producing all twelve pitches of the chromatic scale.’ I would counter that since it is a newly invented instrument, rather than any kind of recognisable Irish harp, it is not possible to situate the Royal Portable within pre-existing Irish harp history in this way.

It is also noteworthy that indigenous Irish music doesn’t require such a scale, so these – and all of Egan’s ingenious string pitch-changing inventions – are exciting developments only if one is looking at them from a European art music – or other non-Irish – perspective.

It is not only the instrument itself that came from outside an indigenous Irish aesthetic: the students who played Egan’s wire-strung Society harps were at least taught by old Irish harpers and/or their students, but Egan’s aristocratic patrons, playing his Royal Portable and pedal harps, were not part of any such Gaelic music tradition. They belonged to the European art music culture of their Anglo-Irish world.

O’Donnell takes Egan to task for his marketing sleight of hand in an 1817 advertisement in which he presents his double-action harp as the ‘Native Instrument of Erin’ yet she doesn’t query his characterisation of that instrument’s little sister – the Royal Portable – as ‘Irish’. Questions around what determines an instrument’s cultural identity, and how that might be defended or challenged, would be an interesting and relevant avenue to pursue here.

I also wonder, in general, why more account is not taken of Egan’s pedal harps and why they remain outsiders in discussions of Irish harp history. Admittedly bigger and less curvy than the Royal Portables, they were also built in Dublin, could equally be green and be-shamrocked, and had an ‘Irish’ repertoire that over-lapped with that of the Royal Portable. As much a part of the overall picture of harping in Ireland as the other nineteenth-century harps, they were still played in the decades after the smaller Egan had fallen out of fashion, and are arguably much closer in design to the Royal Portable than the Royal Portable is to the early Irish harp.

Pre- and post-1800

In her book, O’Donnell rejects a perception that she describes as simplistic: that of pre-1800 harps and post-1800 harps being two separate traditions ‘defined in oppositional terms…wire-strung/strung with gut, male dominated/female dominated, rural/urban, and oral/literate.’ To be fair, I have myself, at one time or another, probably used 1800 as a dividing line. O’Donnell usefully reminds us that that is not judicious. But the dichotomies she presents above are, in many ways, straw-man arguments. Pre-1800, women played the early Irish harp; early Irish harpers performed not only in cities but also internationally; and some were sighted and literate. And certainly, Thomas Moore and Owen Lloyd and his pedal harp teacher were examples of male performers on the other side of the cultural divide post-1800. With regard to wire-strung v. gut-strung instruments, Egan’s nineteenth-century wire-strung harps for the blind boys taught by the harp societies – and the activities of those city-based societies – are known and documented, as are those of the builder James McFall at the end of that century. The question of where to situate the Society harps culturally is an interesting one, which is not yet settled.

There are, however, unequivocal differences between the indigenous-Irish and the European-centric Anglo-Irish music traditions of the period in question. The profound disparities between early Irish harps and the nineteenth-century gut-strung harps, which would eventually replace them, are clear. The proximity (or otherwise) to the source culture profoundly affected the approach of the performers on either side of that divide. The music performed on Royal Portables and pedal harps was aesthetically far removed from that of the older harp in terms of timbre, technique, tuning, temperament, style and performance practice. A deeper exploration of that cultural dichotomy, and a clear view of the musical performance on either side of it, will help modern scholars and performers come to a better understanding of Ireland’s harp music, as performed then and now. The clarification of these different cultural strands allows us to see that there is no single ‘Irish harp tradition’ but a more complicated overlap and juxtaposition of older and newer traditions.

While I take issue with O’Donnell on some matters, I am grateful for the stimulation that her new publication brings to the field of harp studies in Ireland. It is a valuable resource in an under-researched and under-published field and will help historical musicologists, and others, to think about, discuss, and perhaps reassess, the matters she brings to the fore. This book contains a wealth of information on matters organological, historical, social, cultural, religious and political. By weaving them together, Mary Louise O’Donnell provides the first full-length overview of many aspects of harp history in Ireland that highlight not only how Ireland’s colonial rulers thought about the Irish and how the Irish viewed themselves over the last number of centuries, but how that changed the way they played music.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Published on 1 April 2015

Siobhán Armstrong is a historical harpist, the founder and Chair of The Historical Harp Society of Ireland, and a PhD researcher in the area of early Irish harp performance practice at Middlesex University, London.