A Eunuch's Shadow

There is a strange selfish pleasure a composer receives from a good performance of his or her work. It seems to bestow a sense of affirmation, an optimistic confirmation which can even run contrary to the theme or dominant mood of the piece. An effective interpretation restores an autonomous ratification to the composer; a surge of positive energy that somehow finds parity with the months of toil and preparation and forbearance is recoiled into a condensed moment of grace that lasts the length of the performed work, perhaps a little longer.

These are moments to cherish. Also vital are the responses, whether positive or negative (there is nothing so disconcerting as a mute reaction!) of those who have listened to the work. It has been suggested that the final act of composition is in the performance. Given the nature of music, its essentially temporal, chronological status, perhaps it might be argued that music only finds completion in the unfolding moments of experiential cognisance. It can’t be touched, seen, walked around. It is impossible to hold one phrase still in order to contemplate it, for the next one impresses upon you at once. In a very real sense, music can only be lived; it can only be experienced as our lives are – sequentially. No sooner is a note played but it disappears. What stays, what remains palpable, are the effects it has on us. Our responses.

This may be one reason why reactions to music can vary so much. It may also suggest why writing about music is such a difficult business. Apart from its sequential nature, it is impossible to describe in words what music actually communicates. Clearly, music has meaning, but the liaison it makes with our consciousness takes place somewhere outside the realm of verbal syntactical denotation. It is difficult to decide whether a music phrase is too precise or too vague for language, but for sure, anyone who attempts to capture the meaning of music in words runs the risk of writing gibberish. This hazard makes the music critic’s job an unenviable one, particularly in relation to the assessment of new music, which is what I want to concentrate on here.

However music may provoke our responses, the ‘official’ response to music – the review – regardless of its appraisal, seems to me, by return, nearly always disappointing. The one or two paragraphs given over to a new work in the reviews of the national daily newspapers are almost always (what else can they be?) superficial assessments which are either completely wide of the mark or if partially (or even mostly) accurate require greater exposition, clarification, contextual justification and depth of study to be of any value at all. The exercise remains unconvincing and highlights a few very simple but pertinent questions. What is the role of the music critic? Is the dominant medium through which the music critic assesses new music a valid one? If not, what are the alternatives, and are music critics working in the dominant media adequately attempting to offer deeper, more analytical, more significant insights elsewhere?

To help us come to some conclusions here it should be observed at the outset that music critics work only in reply to the music. Their role is a responsorial one. In fact, they act only with the sanction of the work. Incapable of generating their own initial creative light they are, like the moon, dependant upon the sun so that it may, by its grace, ‘reflect’ some light. In a game of choices, they would always loose, for who would aspire to write about Berio’s Voci if he or she could first imagine that magical piece? Who would prefer to offer insights into Barry’s Chavaux-de-frise rather than be the first to cast it? No. Music criticism remains an orbiting satellite clinging to the gravity of the central, created work. If this point does nothing more it might at least offer a direction for music critics towards humility. For their subordinate relationship to the music, the primary artwork, remains intact even when the piece is a poor one, or they think it so.

Naturally, there are examples of music criticism that are themselves creative and distinct artworks. Krenek’s left-wing-biased socio-political essays on music come to mind. So too do Adorno’s now strangely après la date criticisms on Stravinsky, as do Steiner’s eloquent comparative analyses on music and language. But they remain few, and rarely in the medium through which ‘active’ music criticism takes place do we encounter anything of lasting significance. I understand that it may be unfair to compare the academic music essay to the daily music review, but I make the point in order to suggest some direction away from what sometimes amounts to mere reportage.

Let us consider this medium through which numerous music critics are working. The labours of many enthusiastic critics are handcuffed to the restrictions enforced upon them by the demands of modern journalistic practice. Chomsky has repeatedly explained why the truth cannot be told in three minutes. The whole basis of modern journalism (paper and television) is designed to give controlled synopses of the arguments.[1] It is only fair to point out that most music critics are forced to offer their insights within the Procrustean bed of the modern newspaper trade. This may not be such a problem for the criticism of performance and interpretation,[2] the assessment of which requires perhaps a less analytical and studied approach (although it is true that some performances may very well necessitate detailed comparative and contextual evaluations). However, in relation to new music, it is blatantly clear that the daily newspaper, as it now stands, is not the medium through which proper criticism can exist.

The two-paragraph critique of a new piece of music is simply inadequate and discourteous. It is clearly unfair to the composer who has worked in earnest for many months at least. But it is also unfair to honest music critics and one wonders if the restricted space allotted to them forces a kind of hyper-prose, enticing them into absurdly concise retorts struggling to be adequate to the work reviewed. It might be a reason for the trend in prolixity and ‘cleverness’ one is confronted with in some cases. Clearly, alternatives must be found. There has to be some sort of via media between the academic essay and the modern daily review. Whatever form this takes it is clear that more space would be required. How that is achieved is another question. But, for sure, the miniscule space allotted presently in the national daily newspapers is not only doing a disservice to the composer but also to the talents, where they exist, of the music critic.

Without doubt, the level of debate encouraged by some articles published in Graph magazine (sadly, now defunct) and the JMI, among others, has been exemplary,[3] and so the music journal (or monthly) offers music critics a more realistic opportunity to explore in greater and necessary detail that which they feel should be illustrated. Although, at this juncture, it is worth asking how many music critics working in the dominant media have taken advantage of this channel to flex their analytical and investigative skills to explore and offer insights into the best of new Irish music? The extra space available in the journal would also serve the purpose of exposing those works that simply don’t stand up to deeper scrutiny and assessment. Let’s face it, they exist, and many poor scores evade proper evaluation and analysis in the form most reviews are published. It is unfair to the public (who seek guidance in relation to new music), to the performers (who have to play it), but also in the long run, to the composers concerned. Perhaps the Internet may offer a solution to this problem. Space is limitless as are the opportunities for interactive discussion and debate. It remains to be seen how this medium is acted upon by the present generation of critics.

Specific to the Irish scene, it is difficult for composers to read, without envy, prolonged previews, insightful analyses and reviews of new Irish works of literature and theatre which most of the weekend supplements cover extravagantly. Pages upon pages are given over to these and an ever-increasing number of writing competitions offer exorbitant amounts in prize money. The result is that the world of Irish literature and theatre, its authors and directors, its latest creations, are known to, and followed with curiosity by, the general Irish public; there is a genuine and healthy interaction here that is communal. In sharp contrast, world première performances of new Irish music come and go with little acknowledgement, a short review (perhaps) and no extended discussion of the works or their authors. That frisson of excitement in the arts media when a new novel by Banville is published or a new play by Friel is premièred simply does not occur with new Irish music.[4] The collective artistic consciousness in Ireland (never mind the general public) seems to be unaware of the importance (or, in some cases, even the existence) of contemporary Irish music. The poor ratio of membership of composers in Ireland’s state-sponsored academy of creative artists, Aosdána,[5] as well as the fact that Ireland is still bereft of an annual festival of new music are full proof of this point.[6]

Irish music critics certainly have a role to play in enlivening this sleeping consciousness to its musical environment. They can direct it towards what is worth hearing, and hearing again; to help us evaluate, and through this, to value, that which has intrinsic merit in the development and maintenance of a balanced and rich cultural milieu. This is not a licence to dictate, an invitation to influence the fate of one work or composer to the detriment of another. The school of ‘Barry’s the best, forget the rest’ should hold no water here, its negative influence is corrosive. Conscientious critics should be opening scores, not closing them; they should be nurturing the tentative relationship between composer and public. This last point has particular relevance due to the historically weak position the composer holds in Irish culture allied to a deplorable level, traditionally and currently, of music education here. To counteract this music critics must have the space at their disposal to offer biographical and stylistic contexts; to preview forthcoming works so as to aid the perception and understanding of the prospective audience, to tender reasons (where appropriate) as to why a given work is essential to the enlivening of the state of Irish culture, and, where suitable, to nurture (dare I say it!) excitement about a new work. They must also have the space to explain why a new work should not be considered appropriate for the above considerations. Ultimately, the short review as we know it isn’t really the problem. The difficulty arises because it is nearly always the only appraisal offered. If music critics found the extra space to actively develop their roles through the ways I have suggested, and through different media, it would matter less what was presented in the small review. The pressure on the review to be more inclusive and extensive would be reduced; it would then have a specific role – something of an appendix to, or synopsis of, the more extended observations made by the critic elsewhere.

With suitable space at their disposal music critics might be in a position to fulfil another important task – that of elucidation by means of comparison and contextualisation. They need to have the freedom and skills to untangle the mass of notes, the final generated sound complex. They need to work in reverse, to travel upstream as it were, back through the dispersed sounds towards the fundamental structural points and offer clarification. This requires of the music critic highly developed analytical skills, but again, given the general level of music education in Ireland this seems an even more vital asset. How can Buckley’s orchestral works be properly assessed without knowledge of Lutoslawsky’s refinements of timbre? For that matter (crossing media), how can Deane’s Passage-work be elucidated upon without the understanding of and reference to not only the work of Machado, Benjamin, Celan, Darwish and Neruda, but also the political proclivities of the composer who chose to set them?

But beyond recognising the contexts out of which a new work emanates, music critics must finally come to a valid judgement of merit. This obviously requires them to be vigilant in terms of technical achievement, nuance of style and all other constituents necessary to a fundamentally sound work. But they must, most pertinently, enquire as to the work’s ultimate contribution to the evaluation of our society, what it says, or does not say, about our achievements and failures, about how it adds, if at all, to those achievements and failures; to what extent the work resonates the articulations and demeanour of contemporary consciousness. They must adequately enquire whether the outcry of Deane’s Passage-work is up to the crime; to investigate whether the virtuosic absurdity of Barry’s The Triumph of Beauty and Deceit mocks the dangerous absurdity of contemporary existence or indulges in a gratification of intellectual indifference.

The central deeds here are the asking, enquiring, and investigating, as apposed to the scorning, expurgating or dismissing. This is a most crucial point made in the context of an era that offers the music critic great power and esteem. In the context of the small review space, to criticise negatively without adequate explanation and elucidation seems an easy route and somewhat disingenuous. The point is that other possibilities exist for music critics if only they are willing to pursue them. When Steiner provocatively said, ‘when he looks back, the critic sees a eunuch’s shadow’[7] he was commenting, I think, on the critics position vis-à-vis the initial artwork, that he or she always holds a subordinate position, that without the primary creative act criticism is an infertile practice. Perhaps that statement has broader resonance in the environment music critics (no matter how honest and conscientious they may be) largely work in today. Maybe they should ask of themselves that if they cannot fulfil the roles suggested here, do they conceivably run the risk of impotence?

Notes

1. This is a predominantly American practice but one that is fast becoming commonplace throughout Europe and the rest of the world with the ever-expanding monopoly control of communications and news networks.

2. The practice at the turn of the nineteenth century of providing lengthy reviews of performances, say, in the criticism of George Bernard Shaw, tended to be rather verbose, despite his obvious insight and wit.

3. The perceptive review by Patrick Zuk of Musical Constructions of Nationalism‚ ed. by Michael Murphy and Harry White, (JMI : 2: 2-3) along with the various responses to it have been among the most exciting and well articulated arguments in the Irish music scene in recent times.

4. The astute observer will, no doubt, realise I have not mentioned here the over-hyped coverage in the ‘rag mags’ and ‘Sundays’ of the new breed of ‘Celtic classical’ composer.

5. According to the Aosdána website at the time of writing, membership consists the following: 83 visual artists, 75 writers/poets and 17 composers.

6. Since writing this, Dublin has had the benefit of RTÉ’s Living Music Festival. It remains to be seen whether or not this excellent development becomes an annual event.

7. George Steiner, Language & Silence: Humane Literacy (New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 1998 [1968])

Published on 1 January 2003

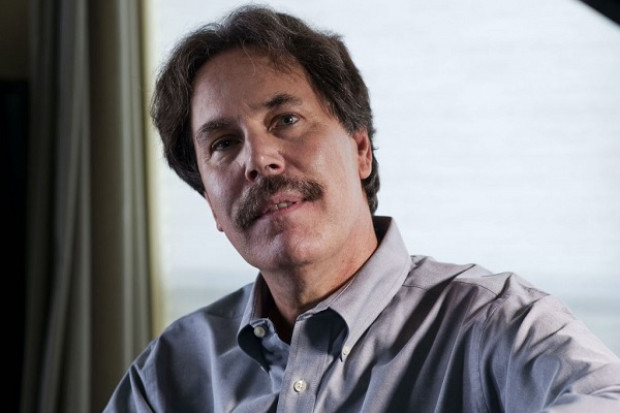

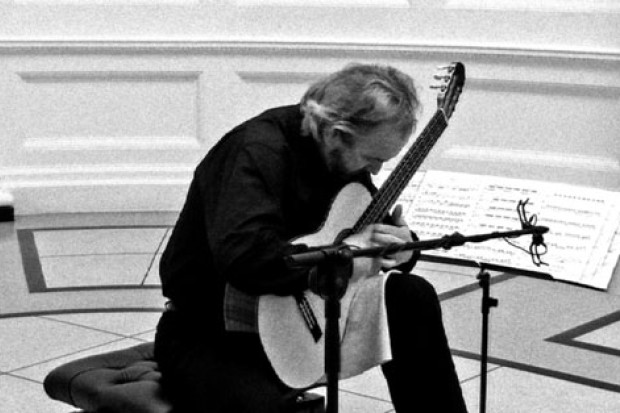

Benjamin Dwyer is a guitarist and composer and the author of 'Different Voices: Irish Music and Music in Ireland'. He is Professor of Music at Middlesex University's Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries.