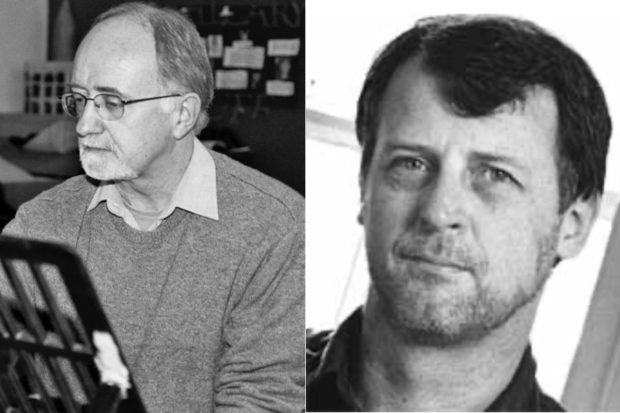

Steve Reich

Encore! – Festival Review: RTÉ Living Music Festival 2006 – Steve Reich

The RTÉ Living Music Festival, Various venues, Dublin, 17-19 February 2006

Featured Composer: Steve Reich

Artistic Director: Donnacha Dennehy

Variations for Winds, Strings, and Keyboards ended the first half of the opening concert of the 2006 RTÉ Living Music Festival and what followed was no ordinary standing ovation. Instead, this was the first opportunity for an Irish audience to acknowledge and thank one of the twentieth century’s greatest artists. As Steve Reich stood on the stage of the National Concert Hall, wearing that famous baseball cap and politely thanking both audience and orchestra, I realised that this festival would be both a retrospective and an introduction to the most influential and loved of all living composers.

Running for three days, the fourth RTÉ Living Music Festival, under the helm of Niall Doyle, Gareth Costello and their colleagues in RTÉ Performing Groups, was the first in the series to live up to its promise of having the featured composer present, the first to avoid the accessibility problems of past events by using city-centre locations, and possibly, judging by the consistently packed venues, the first to significantly recoup costs. The artistic director was Donnacha Dennehy, a composer whose engagement with the Minimalist movement is both evident in his steering of Crash Ensemble as well as his own artistic output. And yet, by including composers such as Feldman, Tenney, Volans, Marshall and Pärt, Dennehy created a refreshing perspective, moving the festival’s focus away from the established contextualisation usually reserved for repeat-pattern Minimalist composers. Instead we saw Reich alongside composers who all share a unique approach to material and, above all, sound rather then structure.

In fact, it was in presenting works by Morton Feldman that Dennehy’s curatorial role was at its most striking and controversial. Surprising as it may be to some, Feldman’s work, despite having minimal qualities, bears none of the hallmarks of Minimalist composition. The structure, always unpredictable, follows no schema, the orchestration is never constant and most importantly there is an emotive depth which Minimalist composers deliberately shunned. Perhaps I am being unkind here, but placing Reich and Feldman side by side is akin to exhibiting the Minimalist painter Frank Stella in the same room as Mark Rothko. The flaw in the analogy is that Reich moved away from the process-derived ecstasy of his counterparts and developed a more emotionally manipulative harmonic language, which in a way moves him closer to Feldman and (unfortunately) makes comparison easier. For example, Friday’s opening concert pitted two such large-scale orchestral works against that extraordinary collaboration between Feldman and Beckett, the non-opera Neither. From the opening bars of Reich’s Three Movements, with its simple yet mesmerising orchestral interplay, to the huge pounding rhythms which end Variations… , I couldn’t have imagined a more exciting opening to a festival. Yet from the moment Neither began, all memory of the Reich seemed to fade. The National Symphony Orchestra’s performance was a revelation of delicacy where interweaving patterns and extraordinary percussion supported a soprano line of rare simplicity.

Saturday’s programming was a daring marathon, running over eight hours and spanning nearly forty years of Reich’s music, most of which was performed by The Crash Ensemble. The first concert contained three Reich pieces, each exemplifying a different approach to technology: the archetype phase piece It’s Gonna Rain (for tape), Pendulum Music (effectively live electronics), and Four Organs (live performance of electronic instruments). These early works are the starkest examples of Reich’s approach, where the relinquishing of control forces the listener to enter into new perceptual modes and yet there is little here to hint at his future direction. The inclusion of Piano Phase might have bridged this gap and was the only work at the festival whose absence I sorely missed. And whilst we speak of absence, it was the poignant inclusion of one early work by Reich’s apparent nemesis Philip Glass that pointed back to a better time in their friendship, the aptly named and brilliantly performed Two Pages for Steve Reich. Also programmed was Jennifer Walshe’s The Procedure for Smoothing Air, one of three festival commissions. Here, the smallest of sounds and most flippant of gestures are amplified and connected into a strangely coherent whole.

Andriessen’s violent Workers Union opened the second concert and was followed by James Tenney’s extraordinary Having Never written a Note for Percussion. This in turn gave breathing space to the next festival commission, Simon O’Connor’s The Paradise – Part III for piano solo. Possibly the festival’s most minimal work, here his characteristic structural inevitability was presented at its most reductive and beautiful. In fact both Tenney and O’Connor’s work point toward that other ur-Minimalist La Monte Young whose omission was no doubt partly due to the infamous difficulties in performing his work. Reich’s Vermont Counterpoint balanced performer with a tape part but unfortunately someone insisted on talking throughout the performance. It transpired that that someone was Reich himself, but thankfully his discussions were drowned out by the Crash Ensemble’s incredible performance of Music for Mallet Instruments, Voices and Organ. In particular, the jazz-influenced performance by soprano Natasha Lohan gained further credibility later in the day when Reich, being interviewed by John Kelly, claimed that Ella Fitzgerald’s scat style was an important influence.

The RTÉ Concert Orchestra’s evening event was the festival’s only disappointment. The ensemble clearly struggled without amplification, and the lack of proper lighting made it look like we were intruding on a rehearsal. The inclusion of Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks was an error as it demanded an uncomfortable adjustment in listening mode. In stark contrast, the following event in the College Chapel, featuring the RTÉ Vanbrugh Quartet and pianist Hugh Tinney was the weekend’s gemstone. Kevin Volans’ festival-commissioned String Quartet No. 10 (!) was a relatively short but striking and complex virtuoso work which appeared to marry some of his more recent approaches to material with earlier structural methods. This was followed by an immaculate rendition of Feldman’s Piano and String Quartet in which the difficulties of performance remained transparent throughout and seemed more precise than any recordings or performances I have experienced. But it is difficult to remain comfortable sitting on the hard chapel pews and the effect of nearly seven hours of this marathon almost tempted me into skipping the day’s final show. But how could I miss a performance of Clapping Music by the composer himself? The reality turned out to be disappointing, but Kate Ellis’ brilliant performance of Reich’s Cello Counterpoint from 2003 was more then conciliatory and it seemed that Reich can still work his magic.

Sunday’s concert in the Project Arts Centre got off to a somewhat shaky start. The Vanbrugh Quartet’s programme demanded sound enhancement, yet despite employing two of Ireland’s finest sound engineers, technical difficulties beset the first two pieces. The first of these, Ingram Marshall’s Fog Tropes II, an inversion of the original 1982 concept, was a disappointment. Next was Reich’s recent and unfamiliar Triple Quartet and within a few moments it becomes apparent that both cello and first violin had technical difficulties. Despite the audience suffering repeated bursts of noise the quartet played through till end. Luckily, the final piece, Different Trains, worked well and it was amazing to see the interaction between the tape parts and the quartet. Only, this was not the final piece… we were asked to sit through the Triple Quartet once again due to the previous problems. In the end the Vanbrugh pulled of a brilliant performance with no hitches and it was good to hear these two performances in quick succession.

A quick hop in a taxi and it was back to the National Concert Hall again, this time to hear the National Chamber Choir with Ensemble Modern. At this stage my spinning mind was relieved to find much of the programme devoted to choral music by Reich, Pérotin, Pärt and Machaut. Early music techniques such as organum have had much influence on Reich’s approach, but as I listened to Pérotin’s Viderunt omnes (c. 1198) and Machaut’s Messe de Notre Dame (c. 1360) I was reminded of Picasso’s reaction to seeing the cave paintings at Lascaux: ‘We have learnt nothing’. Drawing from an even earlier musical tradition was Reich’s Drumming Pt.1, performed by four bongo players from the Ensemble Modern. This was without doubt the festival’s most virtuosic event and although ostensibly a piece about rhythm, it was in fact the ‘metamusical’ elements, in which the harmonics of each of the pitched drums creates a voiced interplay, which became the focus here.

The evening’s final concert pitted Reich’s 1976 masterpiece, Music for 18 Musicians, against a recent work which Reich regards as one of his most important, 2004’s You Are (Variations). This later work was presented first and contained some surprisingly complex harmonic structures although perhaps relied too heavily on previously developed techniques to stand out as a landmark work. Not so Music for 18 Musicians, which despite its age is without doubt Reich’s greatest. To hear it being played in the National Concert Hall with the composer present must surely rank as one of the finest musical moments that venue has ever seen. And so it ended, the audience cheered the man for the last time; Reich, still wearing his little cap, couldn’t stop smiling and neither could we.

There is just one niggling issue which must now loom large: how on earth will RTÉ top that?

Published on 1 May 2006