The Beach Boys

Can Pop Achieve the Sublime?

What place has the sublime in popular music? The sublime, that which terrifies, that which appalls and that which creates awe, has become newly eroticised aesthetic territory where terror and pleasure are found not to be opposed, but to be symbiotic.

The psycho-aesthetic state of the sublime has always been with us, but it has only been in recent centuries that it has been articulated as such. In contrast to classical theories of art, which concentrated unswervingly on the unity of aesthetics and pleasure, philosophers from the seventeenth century onwards began to give accounts of the dual pain and pleasure that some examples of art and nature aroused in them.

In the natural world, something that demonstrates to us an immensity outside ourselves, that exposes both our possible destruction and our oneness with nature, such as an earthquake, creates a sublime impression. Edmund Burke wrote in 1756 of art which celebrates an ugliness of form, character or subject, and which communicates an intense, dangerous, sublated pleasure. (‘Ugly’ here being relative to the formal balance and complementary proportions of what was understood to constitute the ‘beautiful’ in classical styles.) Thus, in music, something like Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge, with its fervent emotion and its incessant formal ruptures, creates this similar, sublime feeling of wound-up, rapt, awe and fear. Theories of the sublime attempt to describe that currency of pain and desire, something captured in the dual urges of masochism towards pleasure and pain, or rather pleasure out of pain.

Jean-Francois Lyotard has written most extensively on the notion of the sublime in modern times, often seeing it where syntax is cracked and style is pushed to the boundaries of convention. The sublime, for Lyotard, is at the centre of the modernist project; it is discontinuity and it is an aporia. It is the dislocation of the sense that we are in control of ourselves, so that our awareness of ourselves: from feeling secure, sublime art opens us out to danger, and to ambiguity.

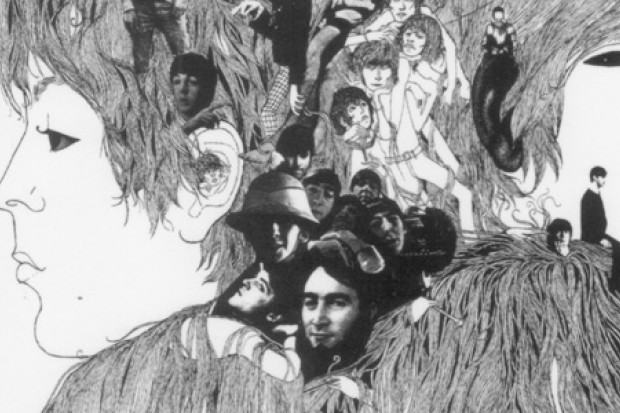

There are many examples of the sublime in popular music, but the wide arc of Brian Wilson’s muse seems most illustrative. The music that Brian Wilson authored, performed (with the Beach Boys) and produced in the 1960s is an exemplification of how popular music has in fact expressed the sublime. An impression of the sublime is often about expectation, and the way in which Wilson’s music refutes, breaks apart, and displaces those expectations actually asserts the sublime as a fundamental aesthetic principle.

Brian Wilson’s songs from the early sixties – at least those that guaranteed the fluffier aspects of his fame – revelled in a light and transparent ‘yes’: yes to the spirit of post-war youth culture, yes to the gentleness of young love, yes to benign American consumerism and yes to fun. Musically and lyrically, songs such as ‘Surfin’ USA’ and ‘Little Deuce Coupe’ celebrated and animated anew the conventions of late-fifties rockabilly and vocal harmony music, as well as those of the budding adolescent culture.

Yet Wilson was never afraid to sing his loneliness, of which he had much. The most durable of his early songs are those where his West-streaked muse alighted on the more haunted aspects of his California, those aspects of loneliness and of cruelty that are the darkening whispers that underlie its people’s idea of themselves. The affecting melancholia of ‘Warmth of the Sun’, of ‘In My Room’, of ‘The Lonely Sea’ or, ironically, of ‘I’m Bugged at My Old Man’, are all cases in point: these are songs coloured with consolation as much as pain. Wilson’s more serene, more tranquil affirmations of a caring paternalism such as ‘Hushabye’ and ‘Don’t Worry Baby’ share in this depth of feeling.

Up to and including Pet Sounds, the element of melancholy was brought forward within the boundaries of a redemptive force, whether that redemption was in the musical design, in the lyrics, or in the context of leavening elements of lightness from the surrounding album. His early work dealt in sadness, but it did so always with a certain ear to the beautiful, with a mind for the pleasure of aesthetic wholeness.

For a few vital years after Pet Sounds, just as he himself turned away from the public and towards the void by largely abandoning the leadership of the Beach Boys and developing a dangerous dependence on food and drugs, some important examples of Wilson’s music correspondingly abandoned, to some (though decisive) extent, the sheen of wholeness, which qualified the despair of such songs as ‘Caroline No’. This later work, heavy-breathed to the earlier lightly-sung, explores the twilight impulse of an anguished mind.

By feeling around in the theatre of American memory for mythical topoi of national identity, by groping through indeterminate patterns of form and figuration for a dreamed pop syntax full of fissure and trauma, and by designing onyx textures of teeming vocal caverns that circle on iconic lyrical motifs, Wilson’s music, particularly songs such as ‘Surf’s Up’, ‘Til I Die’, ‘Wind Chimes’ and ‘I Went to Sleep’, begins a seminal communion with the sublime. As Leonard Bernstein remarked of ‘Surf’s Up’, it is ‘beautiful in its obscurity.’

‘Surf’s Up’ was written originally as the centrepiece of Smile, but in 1971 it was released in a portmanteau version with an elaborated adaptation of another Smile song, ‘Child is the Father of the Man’, now forming the coda. The track is a revenant piece of sound poetry full of pathos for a lost and perhaps non-existent American past. It is, sonically, haunted by gestures from that Americana of the mind: the Woody Woodpecker trumpet flourishes, the Ginsberg-esque, psychedelically enriched and freely associative lyrical idiom (courtesy of Van Dyke Parks), the vivid and sensitive chamber jazz arrangement (piano, bass, trumpet, horns, drums and percussion), the intricate weaves of the melodic line and the ornate and flushed tonality of Golden Age American composers such as Gershwin and Kern – all these elements contribute both to its directness and, in their dislocation, its enigma.

The lyrics move through an obscured and darkly-lit entombment of America: ‘Hung velvet overtaken me / Dim chandelier awaken me, / to a song dissolved in the dawn. (Bygone, bygone.) / The music hall a costly bow / The music all is lost for now / To a muted trumpeter swan. (Bygone, bygone.) /Columnated ruins domino.’ In a similar way, the chord sequence, full of inversions, twisting chromatic leaps and added-note fluorescence, seems to questioningly tumble through conventional pop syntax and convention in a hauntological daze that never leaves the listener settled in one place. When the ghostly apparition of pre-breakdown Brian Wilson emerges (his vocal recording from 1966 was used), haloed both by the leap from one unstable minor chord to another, and by the modulation of the arrangement and production into a distant, celestial wispiness, the song, its creator, and the movement which it eulogises and carries forward in the same gesture, already seem dead.

The song, in its indeterminate form and detail, seems at every moment to be asking, is this happening? It asks in its symbolic coding, ‘Is America real, and, if so, where lies the creative act within its making? What is this terrible beauty which is unconscious to itself as much as it is to its power over others, beauty that is, more properly conceived, sublime?’ The largely choral coda, in opening up to a curved, physically unfastened space of signification, carries this impression to its logical conclusion. This conclusion is an efflorescent (but always enigmatic) statement on the wonder of creativity that sunders and expands the concept of the beautiful to incorporate maculate, confusing elements. As the lyrics suggest, it is the dream logic and the fragility of a child’s view of the world that in the end dominate this song.

In contrast to the baroque lyrical figurations of ‘Surf’s Up’, ‘‘Til I Die’ deals in a direct way with the composer’s deep depression: ‘I’m a cork on the ocean / Floating over the raging sea / How deep is the ocean? / These things I’ll be until I die.’ Over a bed of translucent vibes, piano, bass and constellated vocals, the lonely voice cries into the wilderness of the void. Somnambulant chord sequences and gleaming, liquid textures dislocate any centredness, and place the listener at the edge of consciousness throughout. The shading of the fastness of the lead singer into a group consciousness and the vastness and immanence of that group consciousness in contrast to the direct lyrical treatment of a serious subject, opens up an aporia in the aesthetic matrix of the song, a wormhole of selfhood from which, each time the song ends, it is shocking to emerge.

‘Surf’s Up’ and ‘‘Til I Die’ are weighted by their jewels, like two bald queens. Their cracks, their groping rhetoric and their pathos convey to us something of the power of the sublime, a power that, as described by the writer Georges Bataille, ravishes us by letting us ‘linger in the shadows’, and by putting ‘a moment of our happiness on an equal plane with death.’ That is the force of these songs.

Surf’s Up has recently been released on 180 gram vinyl as part of the From the Capitol Vaults remasters series. www.fromthecapitolvaults.com

Published on 1 October 2009

Stephen Graham is a lecturer in music at Goldsmiths, University of London. He blogs at www.robotsdancingalone.wordpress.com.