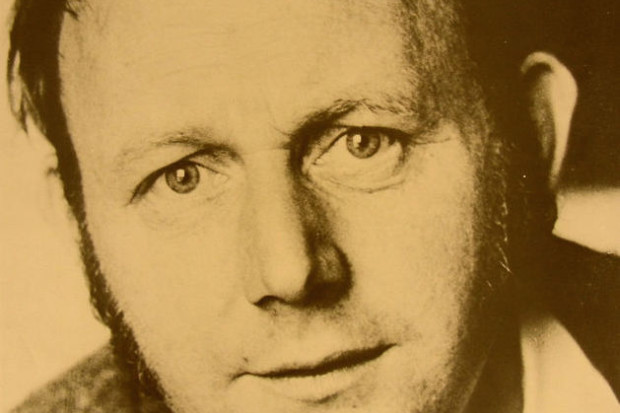

Paul Brady in Rhode Island in 1973 – the cover photo for his new memoir, 'Crazy Dreams'.

Between What Was and What Might Be

The arresting image on the cover of this autobiography might casually be perceived as a ‘rock’ pose; Paul Brady, long-haired, laid back, all in black, looks sternly at the camera. And yet it was taken in the United States in 1973, when he was still with the Johnstons, an early Irish folk group. It speaks to a key theme of this memoir: the interplay between folk, traditional and popular musics in Ireland, and how an artistic identity relates to these genres. The book takes a chronological approach, charting Brady’s journey as a band member and solo artist through the folk and rock/pop scenes.

From Strabane, a border town in County Tyrone, he was lucky – as he admits – to grow up in a reasonably well-off family. His parents, both Catholics, were teachers, and his mother taught in an integrated school at Sion Mills, albeit one with a Protestant ethos. Brady himself attended the school, and he felt its tolerance and openness influenced him throughout his life. At the same time, he also felt something of an outsider – neither parent was from Strabane, and the school was outside the town. The IRA border campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s also left their mark, making him aware of the two-tier nature of society. There was respect for music and the arts at home: his parents sang an eclectic mix of parlour and popular songs, and his father was a keen amateur actor and speaker. Although he went to piano lessons, his ear was drawn more to the popular music of the time, and like many young musicians he worked out versions of these by ear on guitar and piano, as well as interacting with his peers. He recalls how they used to ‘swap chords, tricks and licks. It was a thrill to feel I could not only hold my own but raise a few eyebrows too’.

Transformations

The earlier part of the book gives a real sense of what it was like to experience the different transformations in popular culture which occurred during the 1950s and 1960s. It was fascinating to read about his journey as a listener (and later emulator), beginning with the popular music of his childhood, and progressing to the more visceral and exciting sounds of the rock ‘n’ roll revolution; more than once I found myself checking out and rediscovering the breadth of artists mentioned. An intriguing chapter considers the absence of Irish music in his early life, and underlines how many folk and traditional musicians of this generation only encountered the music later in their lives. Before this, the family’s holidays in Bundoran gave him the opportunity to sit in with and eventually join a resident hotel band that performed for tourists during the season. While concentrating on popular songs, the stirrings of folk were palpable in the occasional ‘come all ye’ and Clancys material.

Yet when the book’s scene shifts to Dublin (where Brady attended UCD from 1964), it was to the emergent blues and rock scene that Brady gravitated to initially. After stints with a number of bands, a chance encounter with Mick Moloney and the Emmet Folk group led to a change of direction, where Brady’s initial ambivalence towards the music was replaced by a whole-hearted embrace of it; he particularly credits his time playing with accordion player James Keane and bodhrán player Carmel Byrne as transformative. It says a lot about the embryonic state of the tradition at this time, not to mention its innocence, that Brady was asked to back Keane without really knowing any of the music and never having backed it before – something hard to imagine happening in the post-revival tradition with its multitude of accomplished musicians. The crucible of O’Donoghue’s pub was also instrumental in his education in this world. Indeed the book is excellent in conveying the excitement of the 1960s, when the worlds of folk, blues and rock intermingled (with some resistance from older traditional musicians). As Brady says, ‘There was the feeling that musically we were all on the verge of something new. In the space of a few months, it became a countrywide phenomenon. Dozens of groups started forming and record companies were signing acts and releasing records. Radio began presenting folk shows and playing these records.’ These were ‘outsiders’ to the mainstream world of the showbands, resisting its commerciality, albeit temporarily; Brady’s wry comment about the ‘scent of money’ underlines how quickly it became commodified.

Paul Brady in New York in 1975

Folk scene of the 1960s and 70s

These issues of commerce, exploitation, control and artistic direction percolate the chapters on the Johnstons, which Brady joined in 1967 (just before being asked to join Sweeney’s Men). The book moves into more conventional band biography here, tracing the outlines of a busy schedule of festivals, media and performances, punctuated by departures (Lucy Johnston and Moloney) and arrivals (notably and auspiciously Chris McCloud). Much is revealed of the competing directions and tensions of the group, as the members and management tried to accommodate both a revivalist and more popular/commercial style. Brady unambiguously positions himself here as growing dissatisfied with folk music and the folk scene, and not for the first time in the book, suggests that musical ambition is incompatible with the conventions and norms of folk music. As he comments, ‘I loved folk music but was increasingly more interested in what might be as opposed to what was.’ A combination of bad luck, a decline in the music industry, and McCloud’s deviousness, manipulation and incompetence, led to the group’s ultimate failure. The trauma of this, and Brady ending up penniless and jobbing around New York, led him back into the folk and traditional world of the 1970s with Planxty.

Now a more seasoned musician, he slotted easily into the group, although management, financial and other issues led to their breakup in 1975. He documents his experiences of the new festivals which sprang up as part of the folk and traditional music network of the 1970s. Central to this of course was his duet album with Andy Irvine, one of the canonical records of the early revival.

Andy Irvine and Paul Brady in 1977 on BBC show Gig In The Round.

Within this section there are also some intriguing details about the recording processes of this early generation of professional folk and traditional musicians. These include some seminal fiddle recordings made with Brady as sole accompanist, including Tommy Peoples’ The High Part of the Road (1976), and three recordings made in the USA for Shanachie, including an all-time classic of traditional music, the eponymous duet album by Andy McGann and Paddy Reynolds (1976). Brady’s respect for musicians who were revered as masters of the tradition was matched by his professionalism; noting that the recordings stretched him as an accompanist, he reveals that he made charts for all of the sets to ensure things went smoothly. There’s also a reminder of how the accompaniment of traditional music was perceived in some quarters as controversial, as the guitar was panned into one channel to allow listeners to ‘mute’ it.

The pivotal chapters return to the provocative theme which suggests that individuality, artistic expression and creativity was not fully possible within the folk and traditional domain. Does the fact that the second part of the book opens with a chapter entitled ‘Getting Real’ suggest that there was something ersatz in the escapism of the folk revival? Brady relates how he felt ‘constrained by the unspoken confines of this new folk world. Stylistically it was all getting too exclusive and the increasingly accepted definition of “Irish music” was narrowing’. (Perhaps not mentioned in the book but relevant, is that this period was also when Irish rock and pop was emerging as a force both within and outside Ireland). This idea – that musicians become restless within the tradition – is hardly a new one (examples that come to mind include the English electric folk bands; the fusions and extensions of the 1970s and 1980s; and even the earlier Ó Riada group had come out of a dissatisfaction of the conventions of the céilí band). The break was gradual – first with a solo album, Welcome Here Kind Stranger – followed by a change in musical direction and focus; in part this was a return to his nascent attempts at songwriting with the Johnstons, but now fully embracing a rock sound (although he supported this change through continued live folk work).

Solo artist

The second part of the book, charting the creation of Paul Brady, the solo artist, is more detailed – but perhaps less immediate and attractive. There are a lot of minutiae of managers, agents, accountants, publishers – a testament to the complex structure of the music industry, and the support needed by a solo artist. There is an oddly long section about Charlie Haughey’s tax exemption for artists, and explanations of copyright and revenue streams – useful for a music business class maybe, but hardly exciting reading. More lively are the various encounters and connections formed along the way; tours with Eric Clapton and Dire Straits gave valuable exposure and opened up avenues; ‘Steel Claw’ got picked up by Tina Turner’s manager for her comeback album Private Dancer; and he taught Bob Dylan ‘The Lakes of Pontchartrain’ backstage in Wembley.

Perhaps his most recognisable song, ‘The Island’, appeared in the midst of this, prompted by the hunger strikes and the escalation of violence in the North. Its ironic criticism and anti-violence stance (‘young boys dying in the ditches / Is just what being free is all about’) was not always received well in the charged atmosphere of 1980s Ireland – despite Brady writing from his own experience and background in Tyrone. The sincerity of the song and its message are underlined by his reflections on its difficult gestation, and the challenge of recording it in the studio.

Reconciling ideas of creativity

Much of the subsequent narrative falls into a similar pattern of gigging, song-writing, recording, and travails with various record companies and representatives. Brady is quite open about his struggles with finishing and mixing projects, as well as his growing disillusionment with the industry and the lack of interest as his career matured. He also provides an insider’s view on the vulnerability and the openness that characterises collaboration and co-writing, based on a gathering of celebrated songwriters he was invited to; paired with Carole King and Mark Hudson, he found himself ‘in a slight daze as he faced the two of them and had to pinch myself a few times’.

The pace of the book quickens towards the end, when (as with many musicians) their focus shifts away from creativity, and onto maintaining and exploiting a body of work as heritage. A month-long series of concerts and a television series (the source recordings for which were shockingly deleted by RTÉ) exploring the Paul Brady Songbook marked an acceptance with being outside the commercial race. The panoply of guest artists at these included folk and traditional players, signalling a re-engagement with this part of his musical history.

It seems though that Brady has never really been able to reconcile his idea of creativity with his understanding of folk and traditional music – at the end of the text, while he expresses his love for it, he also notes that ‘it no longer interested him as a vehicle for progress’. If he was discomfited by restrictive binaries (folk as old, substantial and good; pop as young, light and bad), then other readers might be similarly uncomfortable by the idea that ‘In Ireland traditional music has always nestled in a political context; that of rebellion, rejection of the old enemy Britain and, to an extent, modernity’. While these traits exist and have waxed and waned over time, I doubt that they define the music, and particularly not in the twenty-first century. Brady’s sharp tone – one of the few times in a generally reserved book that this emerges – where he accuses unimaginative and derivative musicians of leveraging politics, humour or entertainment as a means to success, seems to stem from a hurt and disillusionment with the scene, and perhaps reflects his self-defined perception as an outsider.

Such strong personal commentary is scarce though in a book which focuses mostly on the artist and their career; in many ways it is a memoir of a musical life in the context of the music industry, and of the work and business of music. It’s balanced more towards process and creation, with somewhat less emphasis on creativity than you might expect from a songwriter. And while there are plenty of anecdotes, the book is far from an exposé, and much of his personal life has remained off the page. Nonetheless, it’s well-written and polished, and captures some of the excitement and disappointments experienced in the pursuit of a busy and productive musical career.

Crazy Dreams by Paul Brady is published by Merrion Press. Visit www.irishacademicpress.ie/product/crazy-dreams.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 23 November 2022

Adrian Scahill is a lecturer in traditional music at Maynooth University.