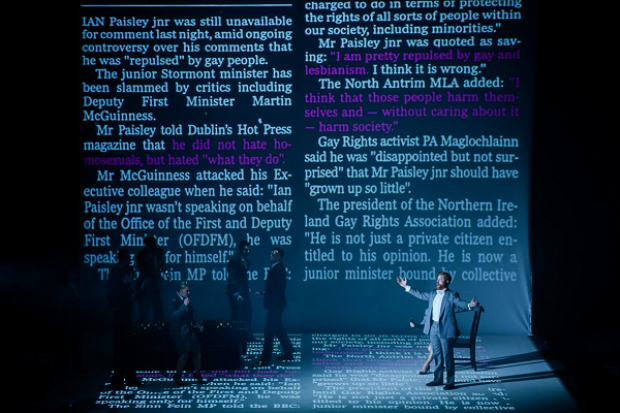

Dorothy Comingore as Susan Alexander in Citizen Kane’s opera scene.

Benny was Family

When Bernard Herrmann and his wife, Lucille Fletcher, stepped off the Twentieth Century onto a sunny California platform in October 1939, it seemed no more than a lark. It was unreal, Hollywood, a dream factory, a world away from the mean streets of New York, and a world away from the new world war that had erupted over there in Europe a month earlier.

Another war the previous year – the Mercury Theatre on the Air’s radio adaptation of HG Wells’ apocalyptic The War of the Worlds – was the spur to this venture. The nationwide hysteria caused by the Halloween broadcast – listeners tuning in late got the scare of their lives, taking fiction for fact – gave its lead, Orson Welles, the kind of headline grabbing notoriety press agents would kill for.

Herrmann was the conductor for the ‘Ramon Raquello Orchestra’ in the production, who play Stardust and La Cumparasita when the Martians crash the Meridian Room of the Park Plaza and zapp the conductor and his men one by one with ray guns. And if Martians weren’t enough, the jazzy dance tunes threw Herrmann off; the production manager, Paul Stewart, had to take the baton and show the uncertain conductor, more partial to Charles Ives – a composer he championed and befriended – than to Hoagy Carmichael, how it was done.

A toe in the water

A toe in the water

Herrmann (pictured) almost didn’t make the West Coast trip. Hollywood was an industry town; studio composers ran ‘a tight little corporation’, a closed shop; no outsiders need apply, including so-called ‘serious’ composers. Wasn’t Schoenberg handed the proverbial ‘Don’t call us, we’ll call you’ line by Irving Thalberg when he requested complete control of The Good Earth, including its dialogue, as a condition of his employment? (The anecdote, slightly embellished, found its way into F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Last Tycoon.) The man didn’t know how to play the game.

Then there was the cautionary tale of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, a Wunderkind of Mozartian proportions who was lured to Hollywood by the director Max Reinhardt. Sure, he’d become part of the set-up – he’d won Oscars for Anthony Adverse and The Adventures of Robin Hood – but what were statuettes compared to being lauded by the likes of Mahler and Strauss? Who listened to his concert music anymore? Who even bothered to programme it? Cries of ‘more corn than gold’ had greeted his violin concerto.

The last thing Herrmann needed was to be seen as a sell-out. He wasn’t planning on staying. He and Lucille – whose journalistic career was taking off with the New Yorker – were merely renting a house, getting a feel for the place. It was business…

It was a legitimate worry. Herrmann’s reputation was rising on the East Coast – his Moby Dick cantata had been accepted by the New York Philharmonic at the urging of its chief conductor, John Barbirolli. As the golden boy of CBS Radio, Herrmann had carte blanche, the in-house composer in all but name, his incidental music and theme tunes airing round the clock. (Verse settings were his speciality; an adaptation of John Keats’ ‘La Belle Dame sans merci’, caught the ear – and won the heart – of Lucille Fletcher, who was visiting backstage.) Herrmann was also the brain behind a series of educational programmes that reached millions who might never have heard Blitzstein or Cherubini or imagined a soirée at Versailles.

Finally, there was his one true love: conducting. More jobs, real jobs, outside radio, were being dangled before him. And, if he played his cards right, who knows? A guest spot with the Philharmonic was in the pipeline; Barbirolli was not only an admirer but had become a firm friend.

‘A new form of dramatic music’

Not that Herrmann was snobby about film. Far from it. Cinema was ‘undoubtedly the most important artistic development of the twentieth century’, and music was the key to the medium, the ‘communicating link between the screen and the audience’. It wasn’t ‘aural wallpaper’ – Stravinsky’s damning verdict – but, according to Aaron Copland, a friend and mentor from his days in the Young Composers Group, ‘a new form of dramatic music – related to opera, ballet and incidental theatre music – in contradistinction to concert music of the symphonic or chamber music kind. As a new form it opens up unexplored possibilities, or should’.

But even the lowliest reviewer fancies himself a gatekeeper, and this strict, Carnegie Hall/Radio City Music Hall divide would provoke Herrmann’s rage, and he an irascible figure at the best of times. (Elmer Bernstein described Herrmann as a ‘virtuoso of unspecified anger’; Oscar Levant, his old Gershwin-circle friend, quipped that he had served an ‘apprenticeship in insolence’.) Only in America did you have ‘film composers’ – every other country had composers who sometimes did films.

Prokofiev, for instance, whose intimate collaboration with Eisenstein on Alexander Nevsky – in some places Eisenstein cut scenes to fit pre-recorded music; in others Prokofiev wrote to the final cut – was the model Herrmann aspired to.

As did Orson Welles.

Herrmann’s being with Welles (pictured, as Charlie Kane) – ‘from before the beginning’ to ‘after the end’ of a production – was a prospect some might have found daunting. Not so Herrmann, a ‘difficult’ person who found other ‘difficult’ people easy to deal with – it was the ‘glad-Harrys’, the nice guys, that he found a pain.

Herrmann’s being with Welles (pictured, as Charlie Kane) – ‘from before the beginning’ to ‘after the end’ of a production – was a prospect some might have found daunting. Not so Herrmann, a ‘difficult’ person who found other ‘difficult’ people easy to deal with – it was the ‘glad-Harrys’, the nice guys, that he found a pain.

Theirs was a tempestuous relationship, characterised by screaming rows, the snapping of batons, accusations of sabotage and the hurling of scripts and scores into the air and at each other. As two huge egos passionate about their work, as demanding of themselves as they were of others, they understood each other perfectly.

And Welles went to bat for Herrmann. When the RKO Pictures boss George Schaefer tried to force Max Steiner – the composer of Gone with the Wind and Casablanca – on him, Welles refused. Benny was family.

Then when Schaefer tried to get away with paying Herrmann peanuts, Welles stood his ground: ‘No – he gets the same as Max Steiner. If he’s good enough to do my score, he’s good enough to get the best price.’

None of this ersatz nineteenth-century romanticism – the overwrought Tristan crescendi, the speeded-up Wilhelm Tell overtures, the tear-jerking Pathétique adagios, all strung together into a merry melody – would do for Welles.

What’s more, Herrmann was to work on the film reel by reel, as it was being shot and cut, side by side with Welles, which contrasted with the usual Hollywood practice of bringing in the composer for a rush job at the post-production stage. He was even going to orchestrate his own music, which was unheard of in the studios, where the assembly-line methods of filmmaking also applied to scoring.

In any case, the thought of someone else orchestrating his music, tampering with it in any way, was anathema to Herrmann; it was like allowing a perfect stranger to put ‘colour to your paintings’; the orchestration was your ‘thumbprint’.

Telling the whole story

As a new kind of picture, Citizen Kane demanded a new kind of score, one that was spare and understated, rhythmic and, above all, apt. Instead of lush harmonies, expressive melodic lines and high-intensity string playing, i.e., schmaltz and hysteria, there would be a cool, detached sound, with almost no vibrato.

Scenes would have bridges, not unlike radio links, so that even five seconds of music should tell the ear that the scene is shifting.

Citizen Kane’s dramatic and emotional values would be made potent through music. He had twelve weeks.

Citizen Kane’s dramatic and emotional values would be made potent through music. He had twelve weeks.

Taking up Welles’s idea of competing motifs that reappear in various guises, two themes immediately suggested themselves to Herrmann, who saw Citizen Kane less as the story of the newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, on whom the character of Charlie Kane was loosely based, and more as a parable of wealth and power. The Destiny or Fate theme, a dark, almost sinister variant on the Dies Irae hymn, conveys the picture’s ultimate message, that ‘all is vanity’; the other theme, Rosebud, reflects a sense of childhood wonder, of yearning, of Kane’s lost innocence. Musically, the prelude tells you the whole story.

Citizen Kane’s showpiece, the opera scene, prompted much discussion. Welles jollied the dubious Herrmann along a few days before shooting commenced with this telegram:

Opera sequence is early in shooting, so must have fully orchestrated recorded track before shooting. Susie sings as curtain goes up in the first act, and I believe there is no opera of importance where soprano leads with chin like this. Therefore suggest it be original … by you – parody on typical Mary Gordon vehicle … Suggest Salammbo which gives us phoney production scene of ancient Rome and Carthage, and Susie can dress like grand opera neoclassic courtesan … Here is a chance for you to do something witty and amusing – and now is the time for you to do it. I love you dearly.

Contrary to popular belief, Citizen Kane’s operatic folie de grandeur was a thinly veiled allusion to the industrialist Harold McCormick’s financing of the Chicago Opera Company for his mistress, a second-rate soprano named Ganna Walska, and not to Hearst’s promotion of his partner Marion Davies’ film career. Nevertheless, Susan Alexander, Kane’s mistress and eventual second wife, resembles Davies in that her talent is misused, smothered; Alexander’s small, charming, salon voice, is simply not up to the demands of grand opera. (Davies, whose bubbly, clowning personality was better suited to knockabout farce, endured the routine costume dramas her sugar daddy deemed respectable.) Struggling with arias a key too high, the orchestra pounding away, the impression is of a poor, put-upon soul sinking into the mire, unable to pull herself out, pathos mixed with tragedy. One’s heart goes out to ‘Susie’, a victim of her husband’s megalomania.

Interestingly, Salammbô, ‘a delightful pastiche’ as Welles called it, has enjoyed a measure of concert success that’s so far eluded Wuthering Heights, Herrmann’s only completed opera, tinkered with for decades and premiered posthumously.

So central is the opera sequence to Citizen Kane that it nearly overshadows other parts in the score no less affecting. Herrmann’s variations on Welles’s favourite Emile Waldteufel waltz, Toujours ou Jamais, for example, is a masterpiece of exposition, a ballet suite in miniature that delicately underlines the montage of an initially happy marriage drifting away into bleak silence. (Herrmann also adapted Waldteufel for the magnificent opening montage Welles’ next film, The Magnificent Ambersons.)

The parting of ways

Citizen Kane’s reception is on the record: critical and commercial success, that is, until a campaign of vilification waged by the Hearst press did for that. Yet despite the establishment’s opprobrium, Herrmann was a winner on Oscar night – not for Citizen Kane, but for William Dieterle’s The Devil and Daniel Webster, a more conventional score finished soon after Welles’ film. It was Herrmann’s first and last doorstop.

After the debacle of The Magnificent Ambersons – Herrmann had his name taken off the credits when studio hacks sliced and diced his score in post-production (Welles was in Brazil on propaganda work and could do nothing) – Herrmann and Welles reluctantly parted ways. Seldom again would Herrmann experience the camaraderie he felt with the Mercury Company, the electricity in the air, the spontaneity. Whereas most directors were ‘musical ignoramuses’, Welles was ‘a man of great musical culture’ and ‘a Rock of Gibraltar’ when it came to making artistic decisions; Welles, for his part, attributed ‘fifty per cent’ of Citizen Kane’s success to Herrmann. ’I was fortunate enough to start my career with a film like Citizen Kane. It’s been a downhill run ever since!’ said the composer himself.

Though Citizen Kane’s score, being basically tonal, is hardly as innovative as the ones Herrmann wrote for Alfred Hitchcock (pictured here with Herrmann) – Vertigo and Psycho are unimaginable without his music – its method of production broke with the Hollywood tradition of music as an afterthought. The mutually beneficial, co-auteur model pioneered by Welles and Herrmann became the ideal (if not the standard); think Steven Spielberg–John Williams, David Lynch–Angelo Badalamenti, David Cronenberg–Howard Shore (‘the Bernard Herrmann of the synthesiser’ – James Woods) and Tim Burton–Danny Elfman.

Though Citizen Kane’s score, being basically tonal, is hardly as innovative as the ones Herrmann wrote for Alfred Hitchcock (pictured here with Herrmann) – Vertigo and Psycho are unimaginable without his music – its method of production broke with the Hollywood tradition of music as an afterthought. The mutually beneficial, co-auteur model pioneered by Welles and Herrmann became the ideal (if not the standard); think Steven Spielberg–John Williams, David Lynch–Angelo Badalamenti, David Cronenberg–Howard Shore (‘the Bernard Herrmann of the synthesiser’ – James Woods) and Tim Burton–Danny Elfman.

Above all, Herrmann’s complex, uncompromising personality comes through his work. As Alex Ross has written, Herrmann’s film scores reflect his own concerns, rather than the concerns of the film: ‘How much of the emotional intensity we feel in these greatest achievements of Welles and Hitchcock – directors not otherwise noted for their romantic touch – comes from the dark passion of Benny Herrmann?’

Published on 16 May 2011

George Rafael is a writer on film and music based in London. He has contributed to Cineaste, The First Post, Opera News, Film Comment and Salon.