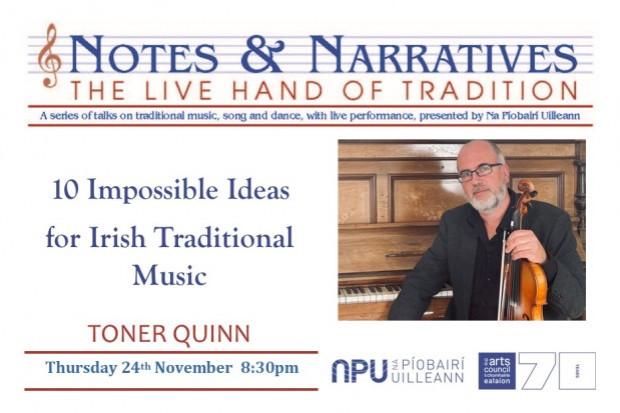

Toner Quinn

"Are You Talking to Me?": Traditional and Classical Music in Ireland

Since the nineteenth century, when nationalism and the use of traditional tunes became a feature of classical music internationally, the subject of traditional music has regularly been referred to in classical music criticism. Ireland is no exception. References to Irish traditional music pepper the writing on Irish classical music through the decades. Indeed, as the musicologist Axel Klein wrote in 2003, ‘one of the most important debates in Irish musical culture has centred around the issue of folk music’.

While in previous decades, extended criticism that focused on Irish classical music appeared only sporadically, in the past fifteen years there has been a notable surge in output. In 1990, the Irish Musical Studies series began and has now produced eight volumes. There has also been Harry White’s The Keeper’s Recital, Music in Ireland 1848-1998 edited by Richard Pine, a collection of essays on Brian Boydell co-edited by Axel Klein, Gareth Cox and Michael Taylor, not to mention several major articles in JMI on the subject of Irish classical music.

As a traditional musician, however, when I read some of the references to traditional music in classical music criticism, there is something about the emphasis on aspects of traditional music that throws me. Portrayed as a vehicle for expressing nationalist sentiment, as a body of melodies to be used in compositions, as a source of interesting rhythmic material, embellishments or modal harmony, or as a force overshadowing the achievements of contemporary Irish composers, I have to remind myself that they are referring to the music that I play, so unrecognisable is it to me in this form.

I have often wondered what purpose, if any, this scenario of presenting only a half-picture of traditional music serves. Is it some imperial process that classical music criticism is compelled to undertake, or is it simply a lack of knowledge of traditional music? Regardless of the reason, the end result is that those involved in traditional Irish music do not respond to Irish classical music criticism, even when it relates to them, and the one-sided picture of traditional music continues to affirm its authority.

An oral tradition

This situation points to the great cultural difference between these two musical genres. There is a very strong tradition of intellectual discourse and analysis running through the Western classical music tradition that is nowhere near as strong in the traditional music of Ireland. Traditional music is, as is well known, an oral tradition, in that its style of performance and, indeed, much of a musicians’ repertoire, is learned predominantly by ear, that is, through listening to other musicians in performance situations such as sessions. In an oral tradition, while the musicians may talk an awful lot about the music, the number who feel compelled to write their ideas down or have them published is very small indeed. There is nothing unusual about this – although in a country profoundly influenced by the Western classical music tradition, it may appear unforgiveable, and indeed hardens the institutionalised idea that traditional music is not to be taken seriously. As I understand it, however, the same silence is evident among practitioners of Indian classical music, so traditional musicians are in good company.

This silence is important when we come to thinking about the writing on Irish classical music in this country over the years. We have to be conscious of the fact that even when traditional music is referred to in an unsatisfactory way, traditional musicians will not be chewing at the bit to respond, to correct any misinterpretations, to challenge any incorrect assumptions about their music. That is not how traditional musicians work.

Consider, by way of contrast, the response of Irish composers Patrick Zuk, Raymond Deane and Benjamin Dwyer to Harry White’s 1998 book The Keeper’s Recital and his accompanying essays. In a relatively short period, they launched a sizeable counter in the form of essays, articles and opinion pieces. It could well be argued, however, that White’s interesting and controversial ideas in this book are as relevant to Irish traditional music as they are to classical music in Ireland, and yet, apart from some work by the writer Barra Ó Séaghdha, there has been very little comment from the traditional music world on White’s work.

Anything but traditional…

Traditional musicians not engaging intellectually with what is being written about them is one thing, but is it all down to them? The fact is that classical music criticism sends out all sorts of signals to suggest to those involved in traditional music that they are not invited to this particular party. We have to consider, again, whether traditional musicians even recognise themselves in much of the discussion about Irish classical music.

Take, for example, something as basic as the vocabulary used. More often than not, were traditional musicians to pick up any of the recent books or essays that have been produced on the subject of Irish classical music, they would come across something called the ‘ethnic tradition’, the ‘native repertory’ or the ‘ethnic repertory’. Then they would come across a phrase such as ‘art music’ or ‘serious music’ and note that its direct opposite is ‘folk music’.

Seldom is the art form that traditional musicians engage in called by the name that they actually use: traditional music. Why is this so? Is it because the term is too imprecise for musicologists and classical music critics? Surely it can’t be any more imprecise than the terms ‘classical music’ or ‘serious music’. Is it because these writers are writing for a wider international audience who mightn’t recognise the term ‘traditional music’? If so, isn’t it about time that we enlightened the international community? Given this situation, I can imagine traditional musicians, on reading the latest debates in Irish classical music and seeing their music referred to by every name under the sun except its correct name, quoting Robert de Niro and asking: ‘Are you talking to me?’

‘Supremely beautiful airs’

I mentioned at the beginning that I wondered was it simply a misunderstanding which compelled classical music criticism to present only a half-picture of traditional music. Rarely is it portrayed as the extraordinarily vibrant art form that I and many others would be familiar with. Instead, traditional music appears as a vast collection of ancient melodies which must be waded through endlessly by Irish composers if they are to satisfy those critics who insist on the need for an Irish Sibelius or an Irish Bartok.

The comments of a University of Cork music lecturer Sean Neeson, in an essay which he wrote in 1959 sum this up well. He wrote: ‘It is true that we have this precious heritage; this corpus of supremely beautiful airs, for the most part unknown outside … this country…. However, beautiful these Gaelic melodies are, they still are mere melodies; many of them, like the best of Plain Chant melodies, complete and perfect in themselves, but outside the polyphonic and harmonic developments in music. We have not yet any significant developed music.’

I quote from this essay because it illustrates one of the primary ways traditional music has been presented in writing about classical music, that is, as simply a great mass of tunes. To the traditional musician’s mind, of course, this is an extremely myopic way of looking at traditional music. It is no wonder that Sean Neeson considered that Ireland had no ‘developed music’, for he was examining only the bare outline of traditional music. The development in traditional music, of course, exists in performance, in the multitude of ways in which that tune can be performed, in the risk, the spontaneity, the invention, the degree of knowledge and experience a performer attempts to infuse into a very compressed musical structure, and the tone and style of the musician’s playing. There is also the interesting trance-like effect that is achieved in traditional music through intimate unison playing combined with relentless tune repetition. These are matters that are never referred to in references to traditional music in the context of Irish classical music.

Responses

I should mention that there are writers who are challenging the divide between these two genres. Two notable examples occurred relatively recently in JMI. In a book review by the Irish composer Benjamin Dwyer, he dedicated some time to respectfully discussing the difference between what he termed the ‘semantic depth’ of contemporary classical music and traditional music. Because the ideas on this occasion resonated with traditional musicians, in the very next issue the traditional musician Emer Mayock responded and added her thoughts to Dwyer’s ideas. In 2002, the critic Richard Pine wrote an article about the relationship between traditional and classical music in Ireland and challenged the use of the word ‘art music’. In a subsequent issue, the traditional musician Donal Lunny wrote a letter in to the magazine to add his thoughts to Pine’s.

These were just two small examples of something that has rarely happened in the past in Irish musical thought – Irish traditional musicians responding to Irish classical music criticism – the divide being normally too wide. It may, however, become more common in the future. Given the time and space, there is a lot that these two traditions could learn from each other.

This is a version of a talk given at the Open Forum of Mostly Modern Contemporary Music Festival 2005, which took place on 2nd April.

Published on 1 May 2005

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music.